Thursday, February 4, 2016

Classic Albums: Bruce Springsteen, Darkness On The Edge Of Town

Listening to Bruce Springsteen's music of the late 1970s and early 1980s, I was always struck at how true it sounded to my small town hometown in rural Nebraska. I was never sure how that could be, since New Jersey seemed to me a much more urban and less isolated place. After relocating to the Garden State, I became enamored with Asbury Park, the rough diamond of a Jersey Shore town, half ruins and half gentrification. On one trip down there we passed through Freehold, Bruce Springsteen's hometown, and it all made sense. It was a small industrial towns in the central flatlands, of similar size and feel to my own hometown. Now I understood how the Boss could sing a line like "there's trouble in the heartland" on "Badlands" so convincingly.

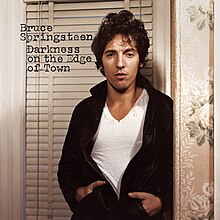

When you grow up in a town like that, there really is something mysterious about the darkness on the edge of town. It's a spooky feeling, knowing that the place you live in is a little oasis in the midst of emptiness, with an outside world out there that just feels so very far away and unattainable. More than any of his albums except for maybe Nebraska, Darkness explores the convulsions tearing post-war American working class life to shreds in the aftermath of the mid-70s recession and slide into neoliberalism. The cover says it all. Springsteen's previous album, Born to Run, has him leaning rakishly on Clarence Clemons, smiling in a classic rock star pose. This time the lettering is starkly type-written, and Springsteen is standing in front of the kind of cheap blinds and wallpaper I saw many times in the less affluent homes at the dawn of Reagan's America. He looks tired and apprehensive, dressed in a white tee and leather jacket, the old greaser uniform out of time in the Age of Limits.

The album starts with the aforementioned "Badlands," fast-paced and hard rocking, but full of dread. The narrator of the song speaks of a "head on collision smashing in my guts" and being "caught in a crossfire that I don't understand." During the summer after my first year of college, I listened to this song over and over again. I was working the day shift at a rubber parts factory in my hometown, a place that seemed, if possible, even more hostile and forbidding to me after a year away in a place where I actually felt comfortable for a change. I also was trying to (unsuccessfully) romance a young woman still in high school who was (of course) dating someone else. (She still obviously liked me, and I wished I had the confidence and finesse to actually tell her how I felt without coming across as a creep.) As frustrating as it was, I at least had a friend, but I couldn't give up my wish that the badlands would start treating me good. This song seemed to articulate so much about how I was feeling at the time, and I can't hear it today without thinking about that summer.

After this point on side one, Springsteen gives up the anthemic rocking, and sets sail for some heavy emotional territory. "Adam Raised A Cain" is most certainly about his contentious relationship with his father, and how you can't escape the pathologies of your parents, no matter how hard you try. It's a slow, grinding rocker with the optimism of "Born To Run" drained away. That feeling of being trapped by circumstances is all over this album, and is more pronounced on "Something In The Night." The guitar drops out, replaced by piano and a Springsteen vocal whose intensity and anger get me every time. The lines "You're born with nothing and better off that way/ Soon as you got something they send someone to try and take it away." This is one of the hardest nuggets of working class wisdom on the album, and he sings it with what sounds like complete anguish. Later songs, like "Glory Days," tell the tale of the bitter reflections of adulthood with an air of fun and wistfulness. This song refuses to sugarcoat the message that most people are in for a big disappointment and are subject to forces bigger than them out to crush their hopes and dreams into the dust.

Perhaps to keep things from getting too dour, Springsteen follows with "Candy's Room," an electric song about the almost insane, desperate longing of young love. Considering the album it's on, this testament of love is tinged with a patina of dread, the tempo almost too fast, making the song and the affection feel fragile. After giving his listeners a dose of the old time Boss religion, Springsteen closes side one with "Racing In The Street," one of the few songs that moves me to tears almost every time I hear it. The title and the chorus reference the joyous anthem of "Dancing In The Streets," but the joy has been drained out. The narrator starts by talking about his hobby of drag racing, but it is a hobby that is really his only reason for living after a day of soul-numbing labor. Whenever I hear it, I can picture a guy leaning on a hot rod smoking a cig in a 7-11 parking lot, watching the sun set and thinking about the night to come. Things get even darker, as he talks about his "girl," who "Stares off alone into the night/ with eyes of one that just hates for being born." That line, which so succinctly and poetically describes what it means to lose the will to live, gets me every damn time. The music itself is so spare and moody, about as far from "Born to Run" as you can get, even if the songs are about the same thing. This song, like the rest of the album, is an unsparing look at real life, something that rock and roll usually works hard to avoid or provide a distraction from. Thus ends side one, making the listener think about some heavy shit while getting up to turn the record over.

Side two is not quite as strong, but still fantastic, and starts with a truly amazing song, "The Promised Land." It sounds like it's sung from the perspective of the narrator of "Racing In The Street," but ten years earlier. He talks about getting his paycheck and going out, hopeful not just for the weekend, but that someway, somehow, his dreary daily life will be blown away by a righteous whirwind. The longing for a better life is saturated in hope, and when he sings the immortal line "take a knife and cut this pain from my heart" it's like a prayer, and not nearly as dark as it sounds on paper. In the week after the 2004 election I listened to this song over and over again, wanting to hope that the insanity and degradation of the political times could somehow be overcome.

After that burst of hope, Springsteen refuses to let the listener off the hook with "Factory," a very straightforward ballad of the soul-crushing nature of factory work. It's a little heavy-handed, but admirable in completely refusing to engage in any romanticization of the working life. The message seems to be that the exuberant hopes of "The Promised Land" are just a mirage for working people once they get older. And it's at this point, that Springsteen decides to give the listener a bit of a break, maybe just to keep the affair from going into full Emile Zola territory. "Streets of Fire" is a rousing ballad, so much so that it's easy to overlook lyrics like "I'm wandering, a loser down these tracks." Then comes "Prove It All Night," the one real pop song on the whole album, tellingly the second to last song, which in the album era would tend to be a bit of an orphan. It's big and bright, like the kind of Top 40-friendly stuff that the Boss would release with greater regularity in the 1980s. Clarence Clemons' sax finally gets a chance to shine out above the murk, which is a welcome addition.

Unlike most albums, the title song comes last, and it sums up the whole album so well. There is the hope of a better life, but also the pain of present reality sung over a rising anthem. The narrator has lost out, and talks about losing his money and his wife, but also that he will "be on that hill with everything that I got...for wanting things that can only be found in the darkness on the edge of town." That darkness is thrilling, it is illicit and full of possibility. The message here is that the larger forces of the world are against most people, but that the fight for meaning and dignity can't be stopped. It's a hopeful ending to a stark album, one that seemed to prophesy the horrors of the Reagan years to come.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment