In 1964 Bob Dylan stopped being a folk singer. It took a year or so for his audience to catch up with this fact. Sure, he still strummed a guitar and blew his harmonica and had that Woody rasp in his voice, but he was no longer writing songs ripped from the headlines. The title and cover of Another Side of Bob Dylan couldn't make anything more explicit. This is not the Dylan you know, but "another side." And instead of his Dust Bowl by way of Minnesota folkie garb, he's dressed like a hipster. That would be Dylan's persona in the mid-60s: an often mean, sneering hipster who still backed up his arrogance with some of the greatest music ever made.

Don't Look Back, the doc of his 1965 UK tour, perfectly captures this moment. He spends a lot of his time putting other people down with the assistance of Bobby Neuwirth. When the latter meanly teases Joan Baez, Dylan just laughs along. Knowing that they were recently romantically connected just makes it harder to watch. Some of the targets did deserve it though, like the pretentious high class British journalists who talk to him with such condescension.

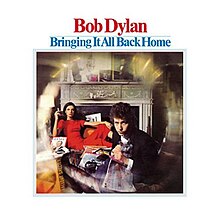

This installment in the Summer of Dylan will delve into the albums from this short moment of transition from folk to what he called "the wild thin mercury sound" that started with Highway 61 Revisited. At that point Dylan is definitively a rock artist playing with a rock band. My periodization might be contentious, since Bringing It All Back Home is often grouped with Highway 61 and Blonde on Blonde as a trilogy, but Bringing It All Back Home came out when Dylan was still performing by himself. I think taking the stage with a band, a la the famous Newport performance, is what really and truly marked the break he was hinting towards in the year leading up to it.

Another Side of Bob Dylan (August 1964)

As I mentioned, this album's title is a statement of purpose. The topical songs are gone, the themes are romance, bitterness, and poetry. It gets a bit raw, and Dylan himself said he regretted releasing "Ballad in Plain D." "It Ain't Me Babe" is a better bitter relationship song but just as acidic. Here he still plays his material solo, but the material is completely different. "It Ain't Me Babe" could perhaps be read less as a song about rejecting a lover because of her demands and more as Dylan's statement to elements of his own audience. They wanted him to be Woody Junior forever, and he wanted to branch out. At this point it's undercover, like a child of a religiously devout family questioning their faith but still making the sign of the cross with them at supper out of obligation but not conviction.

I've never found this to be a completely successful album because Dylan hasn't yet fully taken the plunge into his new musical territory. At the same time, there are several fine songs and some great weirdness on numbers like "Motorpsycho Nightmare."

Rating: Four Bobs

Bootleg Series Volume 6 Bob Dylan Live 1964, Concert at Philharmonic Hall (Recorded October 1964)

This is one of the most interesting entries in the Bootleg Series because it is maybe the best document of Dylan's changing direction. This performance comes after Another Side of Bob Dylan, but some of the revolutionary songs from his next album like "Mr Tambourine Man" are included too, as well as topical numbers like "Who Killed Davey Moore?" He sounds like a man trying to cross a stream, one foot on one bank and one on the other bank. Listening to it again I noticed that the crowd seemed to be most engaged when he was doing his most "relevant" songs, like "Talking World War III Blues."

Joan Baez duets on several songs in the latter part of the set. Dylan is famously improvisational onstage and he seems to be deliberately sabotaging Baez's ability to keep up. This almost completely torpedos "Mama You've Been On My Mind," a normally tender song that sounds rushed here. During his UK tour the next year he stopped having her going on stage to sing with him, another (and more cruel sign) of his exiting planet folkie for uncharted territory.

The mixing of elements makes this a fascinating document, and I keep coming back to it.

Rating: Five Bobs

Bringing It All Back Home (March 1965)

No comments:

Post a Comment