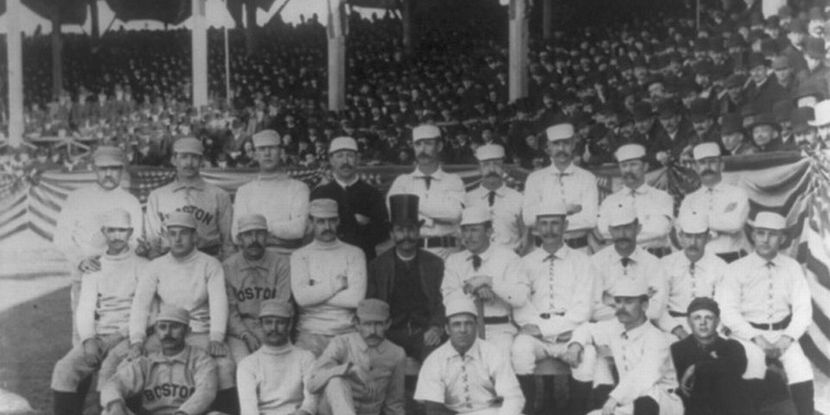

Old Hoss Radbourn giving the finger in this picture is a good allegory for the friction between our myths and historical realities

Right now we are in a moment of great contestation over the American past and our national identity. The storm and cry over "critical race theory" is based in the intense, burning fear many have that the unproblematic, rah-rah exceptionalist nationalism they were indoctrinated in is just not true. Rather than question their assumptions, they are going insane trying to avoid one moment of contemplation.

Baseball can easily fit into the exceptionalist narrative, and there's a reason that "baseball, hot dogs, apple pie, and Chevrolet" has been used to sell cars. The supposed genuine American-ness of baseball required a myth, namely that the game was invented by Abner Doubleday in the bucolic rural village of Cooperstown, New York, in 1839. Even if the museum disavows that fabrication in its own displays today, it's still located in Cooperstown. It still passively affirms baseball as a product of rural small-town "real America," not evolved from older games from Britain and reaching its early popularity in its modern form in the growing big cities of the industrial revolution.

The hall of fame museum does an impressive job of grounding baseball history in its social context and not merely echoing the dominant narratives. It has large exhibits about the women's baseball league, Latin American players, and the Negro Leagues. The almost exclusively white visitors to the museum I witnessed were much less drawn to these exhibits, despite their high quality. Most visitors to the hall are not interested in expanding their understanding of the history of race.

The hall gives plenty of sugar with the medicine, of course. The new film for the hall gave me goosebumps and almost had me crying. This was partially because many of the players who spoke in it have recently passed (Joe Morgan, Bob Gibson, Hank Aaron, Phil Niekro, Tom Seaver), but also because it jammed in so many glorious moments with the players themselves getting a bit overwhelmed. Even my baseball skeptical daughter was moved by it. There's also of course the hall of plaques itself, the game's Valhalla.

It was my second time visiting, and it still felt like holy ground to me. My first impulse upon entering was to genuflect. Here, however, the complicated and tangled history of baseball told in the museum disappears. The museum pointed out that the Boston Red Sox were the last team to integrate, in the hall Tom Yawkey, the man behind that shame, is honored with a plaque. Other racist villains called out in the museum like Cap Anson get laudatory words on their plaques in the hall with no mention of the terrible damage they caused. The likes of Effa Manley and Cool Papa Ball were finally included, but their plaques sit uneasy next to those who excluded them. The hall keeps you from questioning any of this as you look at the plaques in awe.

This experience got me thinking about the difficulties in telling a critical history to the public. In the end, the myth is just too damn attractive to leave behind. Baseball fans just want to believe in baseball. That impulse, when applied to larger American history, is hard to fight.

The solution is thus not smashing all the narratives in a fit of iconoclasm, but to construct new and better narratives. This way of thinking has us replacing Columbus with Pocahontas, Jefferson with Benjamin Banneker, Robert E Lee with Frederick Douglass.

This process can unfortunately devolve into mythmaking or worse when it turns radical figures of the past into safe symbols of consensus. This has already happened to Martin Luther King, who has been reduced in the minds of most Americans to one line in one speech. I was thinking about this going to the Woodstock museum on the site of the festival.

In the first place, a countercultural event having a museum devoted to it seems wrong. The exhibits themselves at least discussed how Woodstock was really a moment where things that had been "counter" just ended up being mainstream culture. As with the baseball hall of fame, a tension existed between laying out the history and giving the visitors the mythology they craved. The exhibits started with the standard self-serving narrative of "the Boomers lived in a cocoon of postwar prosperity that they rebelled against out of concern for making the world a better place."

The museum weirdly also tried to present Woodstock as something that was all things to all people. As I gazed around the almost exclusively middle class white clientele gawking at the exhibits in standard issue suburban American clothing I found that conceit to be a cynical way to get the rubes through the turnstiles. The film showed some great musical highlights, including Santana's mind-blowing "Soul Sacrifice." They did not, however, mention the fact that Carlos Santana was tripping on acid and thought his guitar was a snake. That performance would not have been the same without hard drugs, but no need to freak out the squares, man.

The de-fanging of Woodstock was everywhere. In one of the museum's movies Max Yasgur's son said something to the effect that people were protesting the war but that the American soldiers dying in Vietnam had made the festival possible. This is the usual bullshit when America's most imperialist wars are spun as victories for freedom in America when the poor guys who died in Southeast Asia sadly didn't have any effect positive or negative on the status of freedom in this country. I though of this too when we stopped into a roadside general store nearby for lunch. There was a peace sign American flag hanging outside, but also a POW-MIA flag flying from a flagpole. (If you don't know the pernicious history of the latter read Rick Perlstein's take on it.) The first was to get the tourists in, the second to show that the owners were still good rural "real Americans."

Driving through central New York this weekend I saw quite a few Trump flags and signs and a Confederate flag to boot. The museum's notion that Woodstock made it so the counterculture changed the world seemed laughable. Maybe at the end of the day it was just a different expression of the same individualist ethos that gave rise to someone like Trump. That's hardly the kind of the thing the Woodstock museum would want to cop to.

It's strangely fitting that two such powerful American myths are located less than a hundred miles from each other in upstate New York. It remains to be seen if we can construct a history of ourselves that's capable of being something other than a comforting myth.

No comments:

Post a Comment