Sunday, March 30, 2014

Opening Day Thoughts and Links

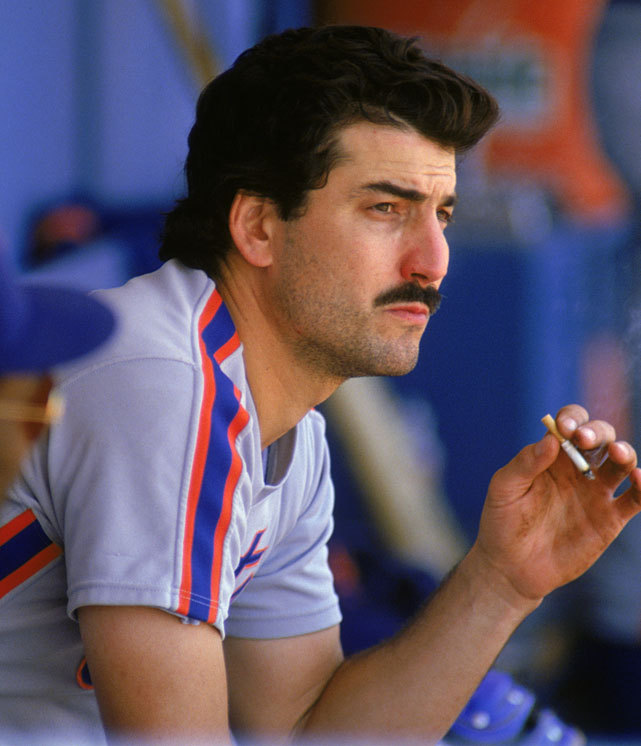

Tonight's game between the Padres and Dodgers marks the official opening of the major league baseball season, although it will not have really begun in my mind until tomorrow's full slate of games. Of all days of the year, opening day is one of my favorites, as it is one of the few days of the year that this old grouch allows himself a little optimism. It is the day that your team, not matter how awful, has hope, with 162 games of possibility stretched out across the six sunniest months of the year. There is even the occasional opening day miracle that can give an especially woeful faithful a jolt of that old time religion. I still remember opening day in 1994, when unheralded Cubs outfielder smacked three home runs off of the mighty Dwight Gooden, giving long-suffering Cubs fans a memory to cherish for years. (Rhodes didn't make it that far in the bigs, but went on to be a great slugger in Japan.)

As I get older I find myself more and more attached to baseball. During the season, it is my daily companion, something I can go to for distraction and even meditation. From April to October, I know that it's always there for me. With each passing year I cherish such daily, reliable pleasures over the more volatile thrills of youth that I have outgrown. I am also perhaps more stirred by the game's deep connection to my boyhood, a time that's been rekindled in my memory now that I have children of my own to play catch with in the back yard. On opening day baseball has come back, and there will be more baseball to come than on any other day of the year. That's something worth getting happy over, in my book.

Here are some relevant links for your opening day enjoyment:

Tuffy Rhodes' Three Opening Day Homers

I mentioned these above, and it is doubly nice to hear the calls by Harry Caray.

"Meet the Mets"

Now that I've moved to New Jersey I have adopted the Mets as my second team, after the White Sox. One thing I like about the Mets, as opposed to the Yankees, is that they have an atmosphere of fun and human frailty about them, rather than the ridiculously self-important tone exuded by the Yankees. The Mets' bouncy theme song, written to drum up support for the team when it came on the scene in 1962, sums up the Mets' spirit well.

Hank Aaron Hits Number 714

I've seen footage for years of Hank Aaron hitting his 715th home run to pass Babe Ruth, but it seems fitting that he hit number 714 on opening day.

Roger Angell on Hideki Matsui's Return to Yankee Stadium

There's perhaps no better writer on baseball than Roger Angell, and his 2010 description of Hideki Matsui's return to Yankee Stadium on opening day is a real gem.

Doug Glanville on Fear

Doug Glanville is one of the few former players to also be a fine writer of the game. In this piece he talks about being a rookie, and hearing from a veteran that even he still had the butterflies on opening day. I still get the same feeling the night before the first day of school.

Wednesday, March 26, 2014

Track of the Week: Lucinda Williams, "Crescent City"

There's going to be a short hiatus on NFI over the next few days, since I am headed down to New Orleans for a friend's wedding. I am incredibly excited, first because I have never been to NOLA and have been wanting to go there ever since I was a little child, and second because I will be seeing many of my dearest friends. My buddy who's getting married worked with me on the contingent track in Michigan, and he was also the one who jumped to teaching at a private school, and gave me the guidance and encouragement to make a similar leap myself. Another great compatriot of those days will be there too, both of us away from family supervision. Hopefully we will return intact. Coincidentally, my two best friends from my time in Texas are going to be in the city for a conference, so I will get to see them, too.

When I get together with these beloved comrades, I feel that we have a bond that passes understanding. We all spent time in the academic trenches together and formed our relationships as a kind of solidarity against the degradations that we endured. Most other people I know, who have not experienced this life, I spare from the old war stories. The tales are either so ridiculous that they can't be believed, or are simply too much like the story of Coleridge's ancient mariner, told hysterically and confusedly. With these friends we get together, drink and talk, retell our stories of the difficult past but sigh with relief over having survived.

I had a hard time coming up with a track this week because I wanted something inspired by New Orleans, and so much amazing music has come from that city that I just didn't know what to pick. Then I remembered my reasons for going to New Orleans. In "Crescent City" Lucinda Williams talks about New Orleans as her adopted hometown, and going back there as a sweet homecoming. It is a place full of good times, good people, and good memories. It's a reminder that as we live our increasingly nomadic lives in 21st century America we have to leave such things behind en route to the next city and the next gig. The people I will see this weekend are people whom I wish I never had to leave behind, that I want so badly to be in my life. I feel sometimes like I have a second, unofficial family that is spread across the four corners of the country and points abroad. Seeing them again lifts my soul, much the same way Lucinda Williams talks about going back to the Crescent City.

Tuesday, March 25, 2014

The Republicans' Two Track Strategy

After losing to Barack Obama handily in 2012 despite his lackluster approval ratings, many in the GOP decided it was time to broaden their appeal. There was much talk of drawing Hispanic and black voters, doing less to alienate young women, of softening the Republican image, of downplaying the Tea Party fringe and avoiding the stigma of the "stupid party."

Despite all of that talk and some sidelining of Tea Party fanatics, Republicans have been doing a lot to alienate the voters they claim to be reaching out to, all in the interests of ginning up their base to get to the polls. In the states there has been a massive wave of anti-abortion legislation, and Republicans are attacking Obamacare provisions for birth control. One of the party's "intellectual leaders" (scare quotes necessary here), Paul Ryan, recently fanned the flames of racial resentment with his coded language of "inner city" poor people too lazy to work. Despite the "small government" rhetoric, there have also been attacks on Obamacare on the basis that it will reduce Medicare payments. (Remember, it's not an "entitlement" if old white people are the overwhelming beneficiaries.)

What are we to make of this?

Obviously, Republicans know that they have a winning strategy for midterm elections. Turnout is already low, and voter ID laws and such in many states will drive that turnout lower, especially among Democrats. When fewer people show up, the side that can motivate its base will win. In politics hate and fear are very powerful emotions, and the GOP has ridden the wave of hate and fear regarding the president among their base to victory. It worked in 2010, it will work again in 2014. (They also benefit from the woefully short attention span of the electorate, who seem to forget that Republicans shut down the government last year in a destructive temper tantrum.) With Citizen's United in effect and the Koch brothers spending freely, the Democrats will have a hard time winning.

Republican leaders also know that this strategy is a big time loser in higher turnout presidential elections, where moderate voters hold the key. After this coming election, expect to see a major pivot among Republicans. Support for immigration reform will magically re-appear, as will outreach campaigns that are more intended to get wary whites to think the GOP isn't racist rather than win over any actual support among people of color. The party establishment knows that they can't nominate an ideologue, (hence Romney winning last time despite lack of base-level enthusiasm) but that they need a candidate with the common touch, unlike the Mittbott 3000. Conservatives have prospered by playing class politics and portraying liberals as cultured elitists; having a venture capital raider who talks like everyone's boss as your nominee doesn't help with that messaging. This is why Christie is still beloved of the Koch brothers, despite his troubles and the wariness of many in the GOP base towards him. He has the common touch, he can be very likable when he needs to be, and has proven an ability to win over moderates in a blue state.

Of course, this can all be derailed if the Tea Party refuses to stay leashed. Its members won't support immigration reform, won't tone down the culture wars rhetoric, and won't even necessarily give their backing to a moderate Republican nominee. The irony for the Republican party is that the very force that wins them midterm elections is the same one that hurts them in the race for the White House. Considering that they have basically decided to use all the levers of obstruction to prevent an opposing president from carrying out his agenda, they might just be willing to accept that situation.

Despite all of that talk and some sidelining of Tea Party fanatics, Republicans have been doing a lot to alienate the voters they claim to be reaching out to, all in the interests of ginning up their base to get to the polls. In the states there has been a massive wave of anti-abortion legislation, and Republicans are attacking Obamacare provisions for birth control. One of the party's "intellectual leaders" (scare quotes necessary here), Paul Ryan, recently fanned the flames of racial resentment with his coded language of "inner city" poor people too lazy to work. Despite the "small government" rhetoric, there have also been attacks on Obamacare on the basis that it will reduce Medicare payments. (Remember, it's not an "entitlement" if old white people are the overwhelming beneficiaries.)

What are we to make of this?

Obviously, Republicans know that they have a winning strategy for midterm elections. Turnout is already low, and voter ID laws and such in many states will drive that turnout lower, especially among Democrats. When fewer people show up, the side that can motivate its base will win. In politics hate and fear are very powerful emotions, and the GOP has ridden the wave of hate and fear regarding the president among their base to victory. It worked in 2010, it will work again in 2014. (They also benefit from the woefully short attention span of the electorate, who seem to forget that Republicans shut down the government last year in a destructive temper tantrum.) With Citizen's United in effect and the Koch brothers spending freely, the Democrats will have a hard time winning.

Republican leaders also know that this strategy is a big time loser in higher turnout presidential elections, where moderate voters hold the key. After this coming election, expect to see a major pivot among Republicans. Support for immigration reform will magically re-appear, as will outreach campaigns that are more intended to get wary whites to think the GOP isn't racist rather than win over any actual support among people of color. The party establishment knows that they can't nominate an ideologue, (hence Romney winning last time despite lack of base-level enthusiasm) but that they need a candidate with the common touch, unlike the Mittbott 3000. Conservatives have prospered by playing class politics and portraying liberals as cultured elitists; having a venture capital raider who talks like everyone's boss as your nominee doesn't help with that messaging. This is why Christie is still beloved of the Koch brothers, despite his troubles and the wariness of many in the GOP base towards him. He has the common touch, he can be very likable when he needs to be, and has proven an ability to win over moderates in a blue state.

Of course, this can all be derailed if the Tea Party refuses to stay leashed. Its members won't support immigration reform, won't tone down the culture wars rhetoric, and won't even necessarily give their backing to a moderate Republican nominee. The irony for the Republican party is that the very force that wins them midterm elections is the same one that hurts them in the race for the White House. Considering that they have basically decided to use all the levers of obstruction to prevent an opposing president from carrying out his agenda, they might just be willing to accept that situation.

Monday, March 24, 2014

The Coen Brothers' Cinema of Existential Despair

As I mentioned recently, I finally saw Inside Llewyn Davis, a film I had greatly anticipated, both for its subject matter -the early 60s Village folk scene- and its creators, the Coen brothers. The Coens are without a doubt my favorite contemporary American film makers, but knowing the storyline of the film, I needed to be in the right emotional frame of mind. The Coens have made many films, all of which fit into a set of genres (which I have listed at the end of this post), and Inside Llewyn Davis, like Barton Fink, The Man Who Wasn't There and A Serious Man, fit in their genre of existential despair. In these films a man (it is always a man, unfortunately) sees his life unravel before his eyes without any solace or comfort. For Barton Fink, Llewyn Davis, Ed Crane, and Larry Gopnik, there is no divine consolation, no happy ending, no way out from the crushing hand of fate.

The Coens' movies usually present humanity as stupid, naive, petty, and cruel. This is sometimes played for laughs, as in Raising Arizona's farcical tale, or dead serious, as in Fargo. Their films of existential despair are hardest to watch, however, because they ring so true. Watching Llewyn fail to achieve his dream despite his talent and aided by his penchant for being his own enemy hit just a little too close for me. It's a very similar character to Barton Fink, a writer who finds his personal hell in LA and whose arrogance and unwillingness to listen to others helps lead to his undoing.

The Coens could make it easier on their viewers by making their protagonists in these films more perfect and more likable. That way, when the audience sees someone being crushed, they can be fully, uncomplicatedly sympathetic, and perhaps avoid the disturbing thought that they too could find themselves in such a state. Barton and Llewyn are both highly unpleasant at times, but they are not bad people, just petty and inept like the vast majority of us tend to be. Ed Crane in The Man Who Wasn't There is emotionally stunted and reserved to the point of catatonia. Larry Gopnik in A Serious Man is probably their most likable "man falling apart," but his inability to stick up for himself and not let people walk all over him makes him incredibly frustrating to watch.

It would be easier to watch these men squirm under fate's cruel hand if they were completely innocent of responsibility for their situations, but they're not. (Larry Gopnik is the possible exception here because he is explicitly a Job-like character being beset on all sides despite his goodness. However, his aforementioned passivity in the face of a cheating wife, sponging brother, spoiled children, and a blackmailing student only make matters worse for him.) Ed Crane meets his downfall after murdering the grotesque man cheating with his wife. Barton Fink refuses to listen to Charlie Meadows, causing the secret killer to enact his revenge on Barton. Llewyn Davis constantly alienates those who love and want to help him and ends up beaten down in a gutter after he takes out his anger at those exploiting him on somebody else.

These Coen films are highly subversive because they go against the grain of the American ideology. We are told that we are the masters of our own destiny, that hard work will be rewarded, that good things happen to good people, and that the universe operates according to moral principles. All of these films show the opposite. They show good people suffering, hard-fought dreams crushed, and cruel people in power prospering. I firmly believe that forty or fifty years from now, these are the Coen films that will be remembered most, because no one else with their sizable audience is willing to probe the cruelty and meaninglessness of existence, and to do it so well.

The Genres of Coen Brothers Movies

Farces

This is my least favorite genre of Coen films, mostly because they lack the depth that animates their other work and the streak of cruelty (pun intended) that gives their work their bite.

Raising Arizona

Intolerable Cruelty

The Ladykillers

Burn After Reading

Dark Noir Murder Tales

In many ways these films are superficially darker than their films of personal despair, and also probe the horrors of this world we live in. At the end of Fargo, when Frances McDormand's character sits in her bed after a harrowing hunting down of the killers, she contemplates the awful world she is bringing a child into. It is one of the most quietly devastating scenes in cinema history, and sums up the Coens' worldview.

Blood Simple

Fargo

No Country For Old Men

Existential Despair

Barton Fink

The Man Who Wasn't There

A Serious Man

Inside Llewyn Davis

Historical Genre Flicks

The Coens love to set their films in the 20th century past, and also to recall older historical genres. They sometimes do this for laughs, as in O Brother, Where Art Thou, which gets its name from a reference to the Depression Era-film Sullivan's Travels while using the Depression as a backdrop. (Superficially The Man Who Wasn't There, which strongly recalls 1940s noir, could be put in this category, but the storyline of a man whose life falls apart puts it in the personal despair genre for me.) I put the almost impossible to categorize Lebowski here because it is a takeoff on Raymond Chandler.

Miller's Crossing

The Huduscker Proxy

O Brother, Where Art Thou

The Big Lebowski

The Coens' movies usually present humanity as stupid, naive, petty, and cruel. This is sometimes played for laughs, as in Raising Arizona's farcical tale, or dead serious, as in Fargo. Their films of existential despair are hardest to watch, however, because they ring so true. Watching Llewyn fail to achieve his dream despite his talent and aided by his penchant for being his own enemy hit just a little too close for me. It's a very similar character to Barton Fink, a writer who finds his personal hell in LA and whose arrogance and unwillingness to listen to others helps lead to his undoing.

The Coens could make it easier on their viewers by making their protagonists in these films more perfect and more likable. That way, when the audience sees someone being crushed, they can be fully, uncomplicatedly sympathetic, and perhaps avoid the disturbing thought that they too could find themselves in such a state. Barton and Llewyn are both highly unpleasant at times, but they are not bad people, just petty and inept like the vast majority of us tend to be. Ed Crane in The Man Who Wasn't There is emotionally stunted and reserved to the point of catatonia. Larry Gopnik in A Serious Man is probably their most likable "man falling apart," but his inability to stick up for himself and not let people walk all over him makes him incredibly frustrating to watch.

It would be easier to watch these men squirm under fate's cruel hand if they were completely innocent of responsibility for their situations, but they're not. (Larry Gopnik is the possible exception here because he is explicitly a Job-like character being beset on all sides despite his goodness. However, his aforementioned passivity in the face of a cheating wife, sponging brother, spoiled children, and a blackmailing student only make matters worse for him.) Ed Crane meets his downfall after murdering the grotesque man cheating with his wife. Barton Fink refuses to listen to Charlie Meadows, causing the secret killer to enact his revenge on Barton. Llewyn Davis constantly alienates those who love and want to help him and ends up beaten down in a gutter after he takes out his anger at those exploiting him on somebody else.

These Coen films are highly subversive because they go against the grain of the American ideology. We are told that we are the masters of our own destiny, that hard work will be rewarded, that good things happen to good people, and that the universe operates according to moral principles. All of these films show the opposite. They show good people suffering, hard-fought dreams crushed, and cruel people in power prospering. I firmly believe that forty or fifty years from now, these are the Coen films that will be remembered most, because no one else with their sizable audience is willing to probe the cruelty and meaninglessness of existence, and to do it so well.

The Genres of Coen Brothers Movies

Farces

This is my least favorite genre of Coen films, mostly because they lack the depth that animates their other work and the streak of cruelty (pun intended) that gives their work their bite.

Raising Arizona

Intolerable Cruelty

The Ladykillers

Burn After Reading

Dark Noir Murder Tales

In many ways these films are superficially darker than their films of personal despair, and also probe the horrors of this world we live in. At the end of Fargo, when Frances McDormand's character sits in her bed after a harrowing hunting down of the killers, she contemplates the awful world she is bringing a child into. It is one of the most quietly devastating scenes in cinema history, and sums up the Coens' worldview.

Blood Simple

Fargo

No Country For Old Men

Existential Despair

Barton Fink

The Man Who Wasn't There

A Serious Man

Inside Llewyn Davis

Historical Genre Flicks

The Coens love to set their films in the 20th century past, and also to recall older historical genres. They sometimes do this for laughs, as in O Brother, Where Art Thou, which gets its name from a reference to the Depression Era-film Sullivan's Travels while using the Depression as a backdrop. (Superficially The Man Who Wasn't There, which strongly recalls 1940s noir, could be put in this category, but the storyline of a man whose life falls apart puts it in the personal despair genre for me.) I put the almost impossible to categorize Lebowski here because it is a takeoff on Raymond Chandler.

Miller's Crossing

The Huduscker Proxy

O Brother, Where Art Thou

The Big Lebowski

Labels:

cinema,

Coen Brothers,

existential despair

Saturday, March 22, 2014

Track of Week: Radiohead, "Go to Sleep"

Radiohead were obviously upset by this state of affairs, and let it show on the more explicitly political Hail to the Thief. It came out in 2003, after the invasion of Iraq, in the midst of intense concern about the future and a feeling by people like me that world events were taking a dark turn. While it is a good album by any band's standards, it's not quite as impressive as the amazing run they had leading up to it. I liked it, but it never really achieved heavy rotation in my personal listening habits, and soon got dusty.

Last year I listened to it again, and realized that I had not given Hail to the Thief a proper hearing the first time around. While there are some weak moments, the best songs are really great, and belong with the best on Radiohead's other records. I developed a real love of "Go to Sleep," with its catchy acoustic riff in a Dave Brubeck-esque time signature segueing into moody electric guitar and later some of Johnny Greenwood's best experimentation on the solo. The lyrics are typical Thom Yorke dread and anxiety, and I love the ominous way he croons "over my dead body" in a high voice. Hearing this song today takes me back to 2003 and my own feelings of dread and anxiety about the world. Perhaps it's hearing the usual neo-con suspects beating the drums of war over the Crimea crisis that's got me thinking about that time eleven long years ago.

Thursday, March 20, 2014

Atwater, Ailes, Rove, and Nixon's Long Shadow

After having recently read a biography about Roger Ailes and seen a film about Lee Atwater, I am more convinced than ever of Richard Nixon's long shadow over our political discourse. While modern-day right wingers might disdain his big government conservatism, Nixon gave the Republican party its blueprint for success. Nixon saw himself as a kind of dirty-faced paladin who did nasty things to protect the nation from the forces of change that he felt were out to destroy America. Nixon broke the law and abused power, but felt that the ends of saving America justified the underhanded means. Beyond his illegalities, he exploited growing social divisions by claiming to represent the "Silent Majority" and he played on white racial fears with his Southern Strategy, which also played well in Northern communities wary of bussing and changing demographics.

Three men who cut their teeth with Nixon have ruthlessly used the Nixonian vision and turned it into a political approach based around demonizing their opponents and playing on bigotry and hatred: Lee Atwater, Karl Rove, and Roger Ailes. Atwater and Rove ran the College Republicans during the Nixon years (and used their own dirty tricks), while Ailes helped turn Nixon into a TV-ready politician. This troika's immersion in Nixon's world manifested itself later in divisive yet effective campaign strategies. Case in point: in the 1988 election George HW Bush looked like a dead duck after the Democratic convention. At that point Atwater and Ailes made it their mission to paint Dukakis as a radical liberal, and were involved in constructing the Willie Horton ad, one of the most shameful episodes in recent electoral history. The personal attacks and playing on racism worked and continue to pay off on Ailes' Fox News to this day.

From the Atwater doc it's obvious to see that he had zero ideological commitment to politics, and got a a major kick out of manipulating a corrupt system, even if it meant engaging in lies and hate-mongering. Ailes, on the other hand, really seems to think that liberals want to destroy the country, and Rove appears to be somewhere in the middle. Since their approach in 1988 paid off so well, they have engaged in similar shenanigans to similar effect. Rove pushed state-level anti-gay marriage referenda in order to get Christian conservatives to the polls for Bush in 2004, effectively exploiting homophobia for his benefit. Ailes has used Fox News to attack the president at every turn, from keeping the phony Benghazi conspiracies brewing to providing the Tea Party with support and propaganda. The Nixonian approach is all over Fox programming, just as it permeates talk radio, in that liberals are constantly and unceasingly demonized. They paint the president as a foreigner, a usurper, illegitimate and un-American. Their politics is less about ideas than a certain kind of tribalism whereby "real Americans" must combat internal enemies.

We're fooling ourselves if we don't think this kind of political discourse is going to have bad longterm consequences. More and more politics seems less about issues than cultural identity, where one's opponents don't just think differently, but somehow embody everything that is wrong in the world. As the so-called "Silent Majority" of older rural and suburban whites keeps dwindling, it gets increasingly inflamed and paranoid, stoked by the notion that they must hold the line by any means necessary else "real America" perish. This is a recipe for disaster, because that former majority will easily see any solution, including violence, as necessary to defend the nation. Cynics like Rove, Atwtater, and Ailes have learned how to maintain power by exploiting the worst of this nation's impulses, but in doing so they are contributing to a polarized society which very well may be impossible to hold together.

Three men who cut their teeth with Nixon have ruthlessly used the Nixonian vision and turned it into a political approach based around demonizing their opponents and playing on bigotry and hatred: Lee Atwater, Karl Rove, and Roger Ailes. Atwater and Rove ran the College Republicans during the Nixon years (and used their own dirty tricks), while Ailes helped turn Nixon into a TV-ready politician. This troika's immersion in Nixon's world manifested itself later in divisive yet effective campaign strategies. Case in point: in the 1988 election George HW Bush looked like a dead duck after the Democratic convention. At that point Atwater and Ailes made it their mission to paint Dukakis as a radical liberal, and were involved in constructing the Willie Horton ad, one of the most shameful episodes in recent electoral history. The personal attacks and playing on racism worked and continue to pay off on Ailes' Fox News to this day.

From the Atwater doc it's obvious to see that he had zero ideological commitment to politics, and got a a major kick out of manipulating a corrupt system, even if it meant engaging in lies and hate-mongering. Ailes, on the other hand, really seems to think that liberals want to destroy the country, and Rove appears to be somewhere in the middle. Since their approach in 1988 paid off so well, they have engaged in similar shenanigans to similar effect. Rove pushed state-level anti-gay marriage referenda in order to get Christian conservatives to the polls for Bush in 2004, effectively exploiting homophobia for his benefit. Ailes has used Fox News to attack the president at every turn, from keeping the phony Benghazi conspiracies brewing to providing the Tea Party with support and propaganda. The Nixonian approach is all over Fox programming, just as it permeates talk radio, in that liberals are constantly and unceasingly demonized. They paint the president as a foreigner, a usurper, illegitimate and un-American. Their politics is less about ideas than a certain kind of tribalism whereby "real Americans" must combat internal enemies.

We're fooling ourselves if we don't think this kind of political discourse is going to have bad longterm consequences. More and more politics seems less about issues than cultural identity, where one's opponents don't just think differently, but somehow embody everything that is wrong in the world. As the so-called "Silent Majority" of older rural and suburban whites keeps dwindling, it gets increasingly inflamed and paranoid, stoked by the notion that they must hold the line by any means necessary else "real America" perish. This is a recipe for disaster, because that former majority will easily see any solution, including violence, as necessary to defend the nation. Cynics like Rove, Atwtater, and Ailes have learned how to maintain power by exploiting the worst of this nation's impulses, but in doing so they are contributing to a polarized society which very well may be impossible to hold together.

Tuesday, March 18, 2014

A Reply to David Brooks' Column About Newark

I have long stopped reading David Brooks' columns, along with most of the Times' op-ed writers, because they have become rather stale and predictable. (Even Krugman has lost his edge.) However, this morning I noticed that David Brooks, the paper's resident neo-con Pangloss, had weighed in on the current mayoral election in Newark.

Like a lot of people in the media, Brooks just can't resist writing about a place he doesn't know and doesn't understand because it helps him score points talking about charter schools, "reform," and the "culture of poverty." In case you don't know, the race is now between two candidates, Shavar Jeffries and Ras Baraka. Both hail from Newark, although Jeffries made his name elsewhere as a high-powered lawyer and later as assistant attorney general for New Jersey. (He also heads a charter school.) Baraka (son of the late poet) is a school principal in Newark and a political activist. While he occasionally invokes more radical, populist rhetoric, he has done a fine job of reassuring local business elites and building relationships with them. Jeffries is more of a technocrat, and is pushing the kinds of corporate style "reforms" (charter schools, etc) favored by elites.

I do not doubt either Jeffries' talent or his genuine desire to make Newark a better place, but I think his priorities are badly misplaced and reflect his immersion in the corporate policy world. Baraka isn't perfect, but I think he cares a lot more about making life better for Newarkers in concrete ways. Anyway, Brooks doesn't really deal with the real Shavar Jeffries or the real Ras Baraka. As he always does, his column devolves into a lazy, simplistic false dichotomy. In this case, it is the "regular vs. the reformer," with charter schools as the focal point (as if that's the issue Newarkers care about most. It isn't, but I'll get to that later.) He describes their differences on education in a typical sweeping generalization wrapped in a false dichotomy:

"Then there is the split, which we’re seeing in cities across the country, between those who represent the traditional political systems and those who want to change them. In Newark, as elsewhere, charter schools are the main flash point in this divide. Middle-class municipal workers, including members of the teachers’ unions, tend to be suspicious of charters. The poor, who favor school choice, and the affluent, who favor education reform generally, tend to support charters."

Brooks makes no mention of the fact that thousands of students in Newark have engaged in walk-outs protesting the neglect of public schools. These students are not "middle-class municipal workers." He has not mentioned the fact that the schools themselves are not run by the city, but by the state of New Jersey, which is proposing to eliminate several schools and fire large numbers of teachers and replace them with Teach For America scabs. He does not mention that Baraka and other high school principals were suspended for the crime of daring to criticize this scheme. He also fails to consider whether charter schools are actually all that effective in the first place, considering that recent research argues that they are not. In Newark they are self-selecting, because parents have to be assiduous enough to apply in the first place, and schools can easily kick out low-performing or disruptive students, an option public schools don't have. (The easiest way to improve test scores is to get weak students out of the testing pool.)

Brooks spends a lot of time burnishing Jeffries' record and biography while disparaging Baraka. For instance, this is how he describes Baraka:

"Baraka has the support of most of the major unions and political organizations. Over the years, he has combined a confrontational 1970s style of racial rhetoric with a transactional, machine-like style of politics. Baraka is well known in Newark and it shows. There are Baraka signs everywhere there."

What does Brooks mean by "confrontational 1970s style of racial rhetoric"? As far as I can tell, it means that Baraka is openly and publicly talking about how racism has harmed and continues to harm Newark, something of which there can be no doubt. A lot of white New Jerseyans like to dispense the lie that Newark was a great place to be until the riots in 67 changed everything. Of course, the truth is that riots were the result of poverty related to deindustrialization, red-lining, and racism, and that the city was horribly oppressive to its black population. After the riots, the rest of America and New Jersey wrote Newark off and just hoped it would die in a gutter somewhere. I have no doubt that if Newark fell of the face of the earth that many in suburban New Jersey would be relieved. When Baraka talks about Jeffries being supported by outside forces hostile to Newark, he's not just blowing hot air or being demagogic, he's drawing on the very real knowledge that Newarkers have of their own abandonment of and exploitation by outsiders. The city has not been able to run its own schools for two decades, and now neighborhood schools are being destroyed and the classrooms filled with TFA neophytes. The parents who are mad about this are not mad because they are union members, they are mad because their children are guinea pigs for corporate "reformers" and they have had their democratic voice over their schools, which people in most communities take for granted, stolen away from them.

By fighting for these parents and students Baraka is not fighting for the status quo, he is actually representing what the majority of people in Brick City actually want, a democratic impulse that has intentionally been repressed. That, Mr. Brooks, is why you see Baraka signs all over Newark. That, Mr. Brooks, is why when I came across Baraka workers or canvassers in Newark I could really feel the emotional weight and momentum behind his candidacy. You see, that's the messy thing about democracy, the people, not the self-appointed experts like yourself, get to have the final say.

As ridiculous as Brooks' attempts to turn Baraka into a modern-day Eldridge Cleaver might be, his talk of "machine politics" is even more ridiculous. Baraka is not a political fixer, he is an activist and an educator. In fact, the biggest political fixer in the area, Democratic boss and Essex County commissioner Joseph DiVincenzo, has thrown his weight behind Jeffries. Baraka threatens Joe D because he is an independent source, and Baraka is instead allying himself with another promising young urban New Jersey politician, mayor Steve Fulop of Jersey City. Of course, Brooks doesn't know that, because he doesn't actually seem to know anything about Newark or Essex County politics. He does however know his usual neo-con narrative, and he tries and fails to cram Newark into it.

Brooks basically lets the cat out of the bag with his last paragraph, a masterpiece of sophistry and cant:

"These contests aren’t left versus center; they are over whether urban government will change or stay the same. Over the years, public-sector jobs have provided steady income for millions of people nationwide. But city services have failed, leaving educational and human devastation in cities like Newark. Reformers like Jeffries rise against all odds from the devastation. They threaten the old stability, but offer a shot at improvement and change."

So basically Brooks thinks Newark is in the state it's in because it pays its city employees too well. Never mind the deindustrialization that destroyed the city's entire economic foundation. Never mind the red-lining and "urban renewal" that obliterated neighborhoods or made them impossible to renovate and replaced them with unlivable, inhumane housing projects. Never mind the fact that suburbanization financed by the federal government via the FHA and interstate highways effectively abetted the disintegration of the city's tax base. Never mind the fact that much of the destruction during the riots in 1967 was caused by the heavy-handed National Guard response.

With that last paragraph Brooks revealed his true intentions. Like so many others, he simply does not give a shit or care at all about the real people of a very real city that I happen to love very dearly. No, he cares about Newark as a symbol, as a political talking point, as an exotic locale whose streets he would never walk in a million years. Newark has a lot of problems, but its biggest problem just might be the people who don't live there.

Like a lot of people in the media, Brooks just can't resist writing about a place he doesn't know and doesn't understand because it helps him score points talking about charter schools, "reform," and the "culture of poverty." In case you don't know, the race is now between two candidates, Shavar Jeffries and Ras Baraka. Both hail from Newark, although Jeffries made his name elsewhere as a high-powered lawyer and later as assistant attorney general for New Jersey. (He also heads a charter school.) Baraka (son of the late poet) is a school principal in Newark and a political activist. While he occasionally invokes more radical, populist rhetoric, he has done a fine job of reassuring local business elites and building relationships with them. Jeffries is more of a technocrat, and is pushing the kinds of corporate style "reforms" (charter schools, etc) favored by elites.

I do not doubt either Jeffries' talent or his genuine desire to make Newark a better place, but I think his priorities are badly misplaced and reflect his immersion in the corporate policy world. Baraka isn't perfect, but I think he cares a lot more about making life better for Newarkers in concrete ways. Anyway, Brooks doesn't really deal with the real Shavar Jeffries or the real Ras Baraka. As he always does, his column devolves into a lazy, simplistic false dichotomy. In this case, it is the "regular vs. the reformer," with charter schools as the focal point (as if that's the issue Newarkers care about most. It isn't, but I'll get to that later.) He describes their differences on education in a typical sweeping generalization wrapped in a false dichotomy:

"Then there is the split, which we’re seeing in cities across the country, between those who represent the traditional political systems and those who want to change them. In Newark, as elsewhere, charter schools are the main flash point in this divide. Middle-class municipal workers, including members of the teachers’ unions, tend to be suspicious of charters. The poor, who favor school choice, and the affluent, who favor education reform generally, tend to support charters."

Brooks makes no mention of the fact that thousands of students in Newark have engaged in walk-outs protesting the neglect of public schools. These students are not "middle-class municipal workers." He has not mentioned the fact that the schools themselves are not run by the city, but by the state of New Jersey, which is proposing to eliminate several schools and fire large numbers of teachers and replace them with Teach For America scabs. He does not mention that Baraka and other high school principals were suspended for the crime of daring to criticize this scheme. He also fails to consider whether charter schools are actually all that effective in the first place, considering that recent research argues that they are not. In Newark they are self-selecting, because parents have to be assiduous enough to apply in the first place, and schools can easily kick out low-performing or disruptive students, an option public schools don't have. (The easiest way to improve test scores is to get weak students out of the testing pool.)

Brooks spends a lot of time burnishing Jeffries' record and biography while disparaging Baraka. For instance, this is how he describes Baraka:

"Baraka has the support of most of the major unions and political organizations. Over the years, he has combined a confrontational 1970s style of racial rhetoric with a transactional, machine-like style of politics. Baraka is well known in Newark and it shows. There are Baraka signs everywhere there."

What does Brooks mean by "confrontational 1970s style of racial rhetoric"? As far as I can tell, it means that Baraka is openly and publicly talking about how racism has harmed and continues to harm Newark, something of which there can be no doubt. A lot of white New Jerseyans like to dispense the lie that Newark was a great place to be until the riots in 67 changed everything. Of course, the truth is that riots were the result of poverty related to deindustrialization, red-lining, and racism, and that the city was horribly oppressive to its black population. After the riots, the rest of America and New Jersey wrote Newark off and just hoped it would die in a gutter somewhere. I have no doubt that if Newark fell of the face of the earth that many in suburban New Jersey would be relieved. When Baraka talks about Jeffries being supported by outside forces hostile to Newark, he's not just blowing hot air or being demagogic, he's drawing on the very real knowledge that Newarkers have of their own abandonment of and exploitation by outsiders. The city has not been able to run its own schools for two decades, and now neighborhood schools are being destroyed and the classrooms filled with TFA neophytes. The parents who are mad about this are not mad because they are union members, they are mad because their children are guinea pigs for corporate "reformers" and they have had their democratic voice over their schools, which people in most communities take for granted, stolen away from them.

By fighting for these parents and students Baraka is not fighting for the status quo, he is actually representing what the majority of people in Brick City actually want, a democratic impulse that has intentionally been repressed. That, Mr. Brooks, is why you see Baraka signs all over Newark. That, Mr. Brooks, is why when I came across Baraka workers or canvassers in Newark I could really feel the emotional weight and momentum behind his candidacy. You see, that's the messy thing about democracy, the people, not the self-appointed experts like yourself, get to have the final say.

As ridiculous as Brooks' attempts to turn Baraka into a modern-day Eldridge Cleaver might be, his talk of "machine politics" is even more ridiculous. Baraka is not a political fixer, he is an activist and an educator. In fact, the biggest political fixer in the area, Democratic boss and Essex County commissioner Joseph DiVincenzo, has thrown his weight behind Jeffries. Baraka threatens Joe D because he is an independent source, and Baraka is instead allying himself with another promising young urban New Jersey politician, mayor Steve Fulop of Jersey City. Of course, Brooks doesn't know that, because he doesn't actually seem to know anything about Newark or Essex County politics. He does however know his usual neo-con narrative, and he tries and fails to cram Newark into it.

Brooks basically lets the cat out of the bag with his last paragraph, a masterpiece of sophistry and cant:

"These contests aren’t left versus center; they are over whether urban government will change or stay the same. Over the years, public-sector jobs have provided steady income for millions of people nationwide. But city services have failed, leaving educational and human devastation in cities like Newark. Reformers like Jeffries rise against all odds from the devastation. They threaten the old stability, but offer a shot at improvement and change."

So basically Brooks thinks Newark is in the state it's in because it pays its city employees too well. Never mind the deindustrialization that destroyed the city's entire economic foundation. Never mind the red-lining and "urban renewal" that obliterated neighborhoods or made them impossible to renovate and replaced them with unlivable, inhumane housing projects. Never mind the fact that suburbanization financed by the federal government via the FHA and interstate highways effectively abetted the disintegration of the city's tax base. Never mind the fact that much of the destruction during the riots in 1967 was caused by the heavy-handed National Guard response.

With that last paragraph Brooks revealed his true intentions. Like so many others, he simply does not give a shit or care at all about the real people of a very real city that I happen to love very dearly. No, he cares about Newark as a symbol, as a political talking point, as an exotic locale whose streets he would never walk in a million years. Newark has a lot of problems, but its biggest problem just might be the people who don't live there.

Labels:

David Brooks,

new jersey,

Newark,

politics

Monday, March 17, 2014

An Incomplete Guide to the Best New Jersey Hot Dog Joints

I must admit to having a love of hot dogs, which in our slow-food, locavore times marks me as both an apostate and a philistine. They are in many ways the symbol of a food culture gone wrong, the chemically-enhanced product of ground-up lips, assholes, and God knows what else. A vegetarian colleague of mine recently said of hot dogs that food shouldn't bounce when you drop it. I understand all these things, but I am also a child of the Midwestern lower-middle class, and thus a great a appreciator of cheap pleasures. I also happen to live in New Jersey, which is an embarrassment of riches for hot dog lovers.

I am lucky to be married to someone with similar predilections, and we have been to many hot dog joints. The New York Times put out their own guide to Jersey dogs awhile back, one I found to be wanting, especially since the author took the usual anthropological tone when crossing the Hudson, as if New Jersey were some kind of exotic land. I'd rather give an insider's perspective, with the caveat that I prefer hot dogs with snap when you bite 'em, a la Grey's Papaya in New York City or The Grand Coney, my old haunt in Grand Rapids, Michigan. Also, based on my time in Chicago, I consider putting ketchup on a hot dog to be a true sign of philistinism. I haven't been to all of the hot dog places in New Jersey, so consider this an incomplete list, and one that I hope to make some additions to.

Rutt's Hut (Clifton)

Rutt's Hutt holds a sentimental place in my heart for having been my first Jersey hot dog experience. Going there is like entering some kind of time portal, which is appropriate since it is hard to get to, perched amidst various ramps and frontage roads for Route 21. There's a hot dog stand area in front, but the best bet is to sit on the bar in the back. The interior is has decorative railings and is paneled with dark wood straight out of 1972. During the summer baseball games will be on the TV, and the conversation at the bar will be interesting. (You can also get regular Coors from the tap, which is a rare treat.) Rutt's Hutt is best known for the "ripper," a deep fried hot dog. It actually tastes a lot lighter than you might think. It also should be topped off with their homemade mustard relish, which I wish I could take trunkload home with me.

Dickie Dee's (Newark)

Regular hot dogs just weren't enough for New Jersey, so back in the 1930s, at least according to the folks who run Jimmy Buff's, the Italian hot dog was created. It's not so much a hot dog as a giant sandwich full of potatoes, onions, and two hot dogs, all of which have been fried together in oil. I have yet to go to Jimmy Buff's, but I have been to Dickie Dee's, a Newark institution. It's probably the only hot dog joint with signed celebrity photos on the wall (including Joe Torre's.) I took a close look at the fryer, and there are many mansions of flavor trapped in the decades of absorbed into it. One Italian hot dog is pretty much all you need to eat to stay full for a whole day.

Libby's Lunch (Paterson)

Some parts of New Jersey have their own local variations of the hot dog, and my favorite is the "Texas weiner." (I am aware of the mis-spelling.) The Texas weiner is a spicy hot dog with meat chili (Texas style) and onions on top. It was invented about a century ago in Paterson, America's first industrial city and home to some beautiful waterfalls of the Passaic River. Go to Paterson to check out the history and the falls, then stop over to Libby's, a small diner whose decor looks like it was last updated in 1983. You will get your Texas weiners on a paper plate, which is probably that cuisine's ideal delivery system, and you will not be disappointed.

Manny's Texas Weiners (Vauxhall)

Luckily for me, I no longer have to drive all the way to the Paterson area to get a good Texas weiner. Right down the road from me is Manny's Texas Weiners, which not only makes a fine dog, but is also a great place to eat. I do not think I have ever been to a restaurant attracting a more diverse clientele, both in terms of race and class. That befits its location, since Manny's sits at the confluence of bourgeois Millburn, working class Vauxhall, and middle and working class Union. Folks are in a good mood there, mostly because they're eating some awesome dogs. It is impossible to leave there without being happy.

Rahway Grill (Rahway)

This is a grungy hole in the wall befitting gritty, blue collar Rahway. Don't let the aged decor and musty atmosphere turn you off, though, these are some fantastic chili dogs, more in line with Coney style that the spicier Texas weiner. Like Rutt's Hut, it's got wood panelling from bygone times, and some talkative characters at the lunch counter. A place this good can easily survive on word of mouth.

Galloping Hill Grill (Union)

This is a favorite stop of my wife's family, and two things put it over the top. First, the buns are made of thick bread, not the white chemical goop that so many hot dog buns are constructed out of. Furthermore, they have birch beer on draft, more flavorful than your average root beer, and the perfect thing to go with the dogs. You can go sit inside, but we always just eat at the tables by the stand in the back, and then walk to the front to get ice cream. Yep, they've got dogs, birch beer, and ice cream in the same location, which pretty much makes it one of my favorite summertime destinations in these parts.

I am lucky to be married to someone with similar predilections, and we have been to many hot dog joints. The New York Times put out their own guide to Jersey dogs awhile back, one I found to be wanting, especially since the author took the usual anthropological tone when crossing the Hudson, as if New Jersey were some kind of exotic land. I'd rather give an insider's perspective, with the caveat that I prefer hot dogs with snap when you bite 'em, a la Grey's Papaya in New York City or The Grand Coney, my old haunt in Grand Rapids, Michigan. Also, based on my time in Chicago, I consider putting ketchup on a hot dog to be a true sign of philistinism. I haven't been to all of the hot dog places in New Jersey, so consider this an incomplete list, and one that I hope to make some additions to.

Rutt's Hut (Clifton)

Rutt's Hutt holds a sentimental place in my heart for having been my first Jersey hot dog experience. Going there is like entering some kind of time portal, which is appropriate since it is hard to get to, perched amidst various ramps and frontage roads for Route 21. There's a hot dog stand area in front, but the best bet is to sit on the bar in the back. The interior is has decorative railings and is paneled with dark wood straight out of 1972. During the summer baseball games will be on the TV, and the conversation at the bar will be interesting. (You can also get regular Coors from the tap, which is a rare treat.) Rutt's Hutt is best known for the "ripper," a deep fried hot dog. It actually tastes a lot lighter than you might think. It also should be topped off with their homemade mustard relish, which I wish I could take trunkload home with me.

Dickie Dee's (Newark)

Regular hot dogs just weren't enough for New Jersey, so back in the 1930s, at least according to the folks who run Jimmy Buff's, the Italian hot dog was created. It's not so much a hot dog as a giant sandwich full of potatoes, onions, and two hot dogs, all of which have been fried together in oil. I have yet to go to Jimmy Buff's, but I have been to Dickie Dee's, a Newark institution. It's probably the only hot dog joint with signed celebrity photos on the wall (including Joe Torre's.) I took a close look at the fryer, and there are many mansions of flavor trapped in the decades of absorbed into it. One Italian hot dog is pretty much all you need to eat to stay full for a whole day.

Libby's Lunch (Paterson)

Some parts of New Jersey have their own local variations of the hot dog, and my favorite is the "Texas weiner." (I am aware of the mis-spelling.) The Texas weiner is a spicy hot dog with meat chili (Texas style) and onions on top. It was invented about a century ago in Paterson, America's first industrial city and home to some beautiful waterfalls of the Passaic River. Go to Paterson to check out the history and the falls, then stop over to Libby's, a small diner whose decor looks like it was last updated in 1983. You will get your Texas weiners on a paper plate, which is probably that cuisine's ideal delivery system, and you will not be disappointed.

Manny's Texas Weiners (Vauxhall)

Luckily for me, I no longer have to drive all the way to the Paterson area to get a good Texas weiner. Right down the road from me is Manny's Texas Weiners, which not only makes a fine dog, but is also a great place to eat. I do not think I have ever been to a restaurant attracting a more diverse clientele, both in terms of race and class. That befits its location, since Manny's sits at the confluence of bourgeois Millburn, working class Vauxhall, and middle and working class Union. Folks are in a good mood there, mostly because they're eating some awesome dogs. It is impossible to leave there without being happy.

Rahway Grill (Rahway)

This is a grungy hole in the wall befitting gritty, blue collar Rahway. Don't let the aged decor and musty atmosphere turn you off, though, these are some fantastic chili dogs, more in line with Coney style that the spicier Texas weiner. Like Rutt's Hut, it's got wood panelling from bygone times, and some talkative characters at the lunch counter. A place this good can easily survive on word of mouth.

Galloping Hill Grill (Union)

This is a favorite stop of my wife's family, and two things put it over the top. First, the buns are made of thick bread, not the white chemical goop that so many hot dog buns are constructed out of. Furthermore, they have birch beer on draft, more flavorful than your average root beer, and the perfect thing to go with the dogs. You can go sit inside, but we always just eat at the tables by the stand in the back, and then walk to the front to get ice cream. Yep, they've got dogs, birch beer, and ice cream in the same location, which pretty much makes it one of my favorite summertime destinations in these parts.

Saturday, March 15, 2014

Track of the Week: Jackson C. Frank, "Blues Run the Game"

I finally got around to watching Inside Llewyn Davis, a film I'd put off seeing despite anticipating it so much. I love the Coen brothers and classic folk music in equal measure, but knowing that its story concerns the trials of someone who must suffer because he is good but not good enough to make it at what he loves meant that I was hesitant to rekindle certain regrets of my own.

It's a great film, of course, not least because of a fine soundtrack of modern versions of the type of songs that defined the folk genre back in its early-60s Greenwich Village heyday. Today we tend to remember the great artists that came out of that scene, like Bob Dylan, or the cheesy popped-up folk hits from the likes of the Kingston Trio or the New Christie Minstrels. In recent years I have been looking deeper into the genre at great performers who don't quite fit either category, since they are too genuine for pop, but never achieved the fame of Dylan or Gordon Lightfoot. Some cherished examples are Richard and Mimi Farina, the Jim Kweskin Jug Band, and Jackson Frank.

Frank had a tragic and difficult life, a tale of woe that makes for some painful reading. It's hardly surprising that a man with these experiences could pen a song as melancholy as "Blues Run The Game." I find its matter of factness to be its most striking element. Frank sings of a broken world where nothing ever turns out right, but does so with a tone of voice that implies that we could hardly expect any better in this life. "Are you really surprised that the blues run the game?" is what he's really asking here. Because if we were to be honest, with all the of the cruelty and suffering in the world, there's no way we could say no.

The earnestness of folk music is easy to parody, and some performers can turn the genre into an exercise in solipsistic emoting. However, when put in the hands of poet, it is capable of beauty and meaning that few other forms of music can match.

Thursday, March 13, 2014

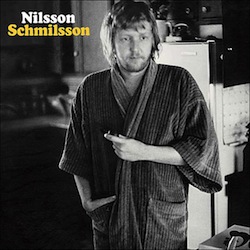

Classic Albums: Harry Nilsson, Nilsson Schmilsson

Harry Nilsson has got to be one of the most unique figures in musical history. He was a great songwriter who made hits for others (as in There Dog Night's version of "One"), yet he was also a fantastic singer with a multi-octive range and the ability to wring the pathos out of a song. That's perhaps why his biggest hit, "Everybody's Talking" was a cover, one his many stellar interpretations of others' compositions. He is also unfortunately known for the squandering of his talent through alcohol and a drunken screaming contest with John Lennon that shredded his vocal cords.

Nilsson put out a lot of good records, but none can really compare to his apex, 1971's Nilsson Schmilsson. It's an album that feels comfortable and homey, a tone set by the cover, showing Nilsson in a bathrobe, and the back, displaying the inside of his fridge. The first song, "Gotta Get Up" is about that most quotidian of tasks, getting up in the morning to get to work. The narrator hurries and hustles to get to his job, but dreams about his lost youth and the good times he had. The next, "Driving Along," continues the theme of observing daily life, and might be this album's secret weapon. Nilsson really reaches the stratosphere with his voice, a moved matched by some great, soaring guitar. It's a reminder that for this album Nilsson had great session musicians and studio magic contributing their best to his songs. The theme of morning continues with the next song, "Early in the Morning," a wonderfully spare cover of the Louis Jordan blues tune, with only a minimalist organ backing Nilsson, allowing his voice to really take over. When I lived in Newark and walked from my apartment to Penn Station down Ferry Street each morning, I loved to listen to this song with the sun barely peaking out over the horizon.

Showing off his impressive versatility, the fourth track, "The Moonbeam Song," is a beautiful ballad complete with strings, languid as a cool June breeze. Suddenly, on the muscular and soulful "Down," the last song on side one, Nilsson shifts into a higher gear. One thing that makes Schmilsson so great is that it never gets stuck in a rut or sticks to a formula. Each song a gem in itself.

Side two opens with the biggest hit on the record, a cover of Badfinger's "Without You." I will admit that it is a little overwrought and overdramatic, but that being said, it has some of Nilsson's best singing. What has always fascinated me about his singing is that he makes it sound so effortless, even while he is belting out the last chorus with such overwhelming force. It is a song obviously intended for the AM radio waves, and while it is not one of my favorite Nilsson tunes, its emotional power seems overwhelming next to tunes like "Love Grows Where My Rosemary Goes." And then, like some kind of mad scientist, he moves on to "Coconut," a silly, catchy number with Caribbean overtones, as if we were not supposed to take the overblown pathos of "Without You" seriously.

Mirroring the first side (remember, we're talking about LPs here, folks) the third song on side two is another cover, this time of the R&B standard "Let The Good Times Roll." He gives it a kind of laid-back vibe, which makes it sound like something that The Dude in The Big Lebowski would listen to while sipping a white Russian. That mellow feeling disappears on the seven-minute long "Jump Into the Fire," a bona fide rock and roll jam. It starts, incongruously, with a heavy bass line that forms the basis of a great, propulsive groove. (There's a reason Scorsese used this song in the frenzied end to Goodfellas when Henry Hill is coming unraveled.) Interestingly, the instruments matter most here, and Nilsson's voice takes a back seat. It's almost as if after backing him so well elsewhere, that Nilsson wanted to let the studio musicians have a chance to really cut loose.

It's really hard to follow such an extended moment of rocknroll exuberance. The next song, "I'll Never Leave You" dials back the energy in favor of piano, horns, and strings balladeering. The horns are ominously minor-key and discordant, not bright and shiny, the strings plucked instead of soaring. It sounds like a sad circus calliope, with Nilsson singing in a forlorn way, his voice somewhat buried. It is a daringly ominous way to end such a catchy, poppy album and hints at Nilsson's own struggles with the dark side.

Albums rarely come any better than this, and the diversity of styles always keeps getting me to come back. I find Schmilsson to be an especially great album for March, a month with unpredictable weather that jumps all over the place (sometimes in the same day), but with the hope for spring always present underneath it all. This album is the same way, the windy lion of "Jump Into the Fire" giving way to the calm lamb of "The Moonbeam Song."

Tuesday, March 11, 2014

Self-Promotional Interlude

In case you guys don't know, I have a new piece up on the Professor Is In about my decision to leave academia for a teaching at a private school. I am honored to be featured there, and happy to be a member of the PII crew to offer advice for others wanting to make the same transition. To be honest, I have had multiple panic attacks today due to the intense memories writing the piece has sparked, which stem my old fears of being attacked again by those who wronged me in the past. I have been heartened by the support and kudos from so many friends on social media that those fears are subsiding. Soon I will be writing some follow-up pieces, so stay tuned.

Monday, March 10, 2014

The Psychological Toll of Contingency

I've happened to talk to a lot of my friends from my time in academia over the last two weeks. Some are contingent faculty, some have moved on to other fields, some are on the tenure track, and some are tenured. The conversations have given me some pretty powerful flashbacks to what my life used to be like, especially on the contingent path.

Contingency is not just common in academia, of course. The proliferation of adjuncts and "visitors" is indicative of a general trend towards disposable, replaceable, and poorly compensated labor in our economy. I have friends and family members in other fields who have had to contend with a lack of job security and crummy pay. They work 35 hours a week at "part-time" jobs that don't provide them with health care. They face lay-offs and "flex time," their certainty and security held hostage by capricious employers who only care about squeezing every last cent out of their workforce.

Those awful attributes of contingency are well known, but I am coming to see that the psychological damage is much worse. When you are contingent, in whatever field, you cannot plan for the future. With each passing year you have no clue if you will have employment in the next year, or whether you might have to move halfway across the country. It is next to impossible to hold down long-term relationships, raise children, and plan for the future when the future is always so uncertain. Life gets put on hold, then seems out of reach. You end up blaming yourself for being unable to do things that forces beyond your control won't let you do.

Even worse, it is easy when you are contingent to internalize self-hatred, because you are constantly told that you are worthless. Your employer holds you at arm's length, and metaphorically (or even literally) asks you to go in the servants' entrance. Your employer doesn't compliment you on a job well-done, but cracks the whip whenever there's the slightest student or customer complaint, no matter how ill-founded. You are there to perform menial tasks, do as you're told, and do as little as possible to be seen or heard. It is no way to live, and it makes those subjected to it feel as if they are completely lacking in value. They might explode in occasional flashes of anger, or they may merely slowly die inside. Either way they do not have the power to change their situation.

Sometimes when you're contingent you feel as if you're going crazy. You follow all the rules, you do a great job, and then after proving yourself time after time, you're still stuck on the treadmill, or even given the boot. You try to apply for a full-time job at the place that employs you full time, and despite your track record, they won't even call you back. The university that you have given your blood, sweat, tears, and weekends to seems to have no problem turning around and cutting your classes or even laying you off when it reaches a slight bump in the fiscal road. Hell, after three years of perfecting your craft they just might turn you loose because they only hire contingent labor for three years because the churn drives down wages and ends any uncomfortable questions about why some people have tenure and some people don't.

Why? Because the powers that be simply do not give a shit about you or any of the other contingent laborers. You are a line on a ledger, a replaceable part, a gear in the machine to be tossed out capriciously for another. Deep down you know this, you take it to heart, and it makes your soul sick because there isn't a goddamned thing you can do about it.

Too many people I care too deeply about are trapped in this world, be they contingent professors, corporate employees, or in the creative fields. The lack of compensation and security is bad enough, but the psychological hell contingency creates is intolerable, and ought to be a call to arms.

Contingency is not just common in academia, of course. The proliferation of adjuncts and "visitors" is indicative of a general trend towards disposable, replaceable, and poorly compensated labor in our economy. I have friends and family members in other fields who have had to contend with a lack of job security and crummy pay. They work 35 hours a week at "part-time" jobs that don't provide them with health care. They face lay-offs and "flex time," their certainty and security held hostage by capricious employers who only care about squeezing every last cent out of their workforce.

Those awful attributes of contingency are well known, but I am coming to see that the psychological damage is much worse. When you are contingent, in whatever field, you cannot plan for the future. With each passing year you have no clue if you will have employment in the next year, or whether you might have to move halfway across the country. It is next to impossible to hold down long-term relationships, raise children, and plan for the future when the future is always so uncertain. Life gets put on hold, then seems out of reach. You end up blaming yourself for being unable to do things that forces beyond your control won't let you do.

Even worse, it is easy when you are contingent to internalize self-hatred, because you are constantly told that you are worthless. Your employer holds you at arm's length, and metaphorically (or even literally) asks you to go in the servants' entrance. Your employer doesn't compliment you on a job well-done, but cracks the whip whenever there's the slightest student or customer complaint, no matter how ill-founded. You are there to perform menial tasks, do as you're told, and do as little as possible to be seen or heard. It is no way to live, and it makes those subjected to it feel as if they are completely lacking in value. They might explode in occasional flashes of anger, or they may merely slowly die inside. Either way they do not have the power to change their situation.

Sometimes when you're contingent you feel as if you're going crazy. You follow all the rules, you do a great job, and then after proving yourself time after time, you're still stuck on the treadmill, or even given the boot. You try to apply for a full-time job at the place that employs you full time, and despite your track record, they won't even call you back. The university that you have given your blood, sweat, tears, and weekends to seems to have no problem turning around and cutting your classes or even laying you off when it reaches a slight bump in the fiscal road. Hell, after three years of perfecting your craft they just might turn you loose because they only hire contingent labor for three years because the churn drives down wages and ends any uncomfortable questions about why some people have tenure and some people don't.

Why? Because the powers that be simply do not give a shit about you or any of the other contingent laborers. You are a line on a ledger, a replaceable part, a gear in the machine to be tossed out capriciously for another. Deep down you know this, you take it to heart, and it makes your soul sick because there isn't a goddamned thing you can do about it.

Too many people I care too deeply about are trapped in this world, be they contingent professors, corporate employees, or in the creative fields. The lack of compensation and security is bad enough, but the psychological hell contingency creates is intolerable, and ought to be a call to arms.

Sunday, March 9, 2014

Have The Sixties Finally Faded?

Growing up in the 1980s meant I knew a lot about the 1960s. That might sound strange to you, but the second half of the 1980s featured a strong and intense wave of sixties nostalgia. Reruns of The Monkees on MTV were so popular that the Pre-Fab Four (minus Mike Nesmith) made a successful comeback. Other groups followed suit to cash in on the reunion circuit, from Jefferson Airplane to The Who. Classic rock radio began to take form, meaning that I soon knew the music of that era just as well of the hits of my own day. Not an hour of cable television viewing could go by without seeing the commercial for the "freedom rock" compilation. Films about Vietnam, from Platoon to Missing in Action came fast and furious as the country began to grapple with the war's legacy. Growing up I seemed surrounded by that conflict, from the touring version of the wall memorial I saw in a nearby town to television commercials for the Time-Life book series about the war. Twentieth anniversaries of events like Woodstock and the "Summer of Love" got massive coverage in the media.

At the time the 1960s looked like a much more interesting time to be alive than the reactionary, frivolous eighties. I remember a stand-up comic of the time making the same comparison, saying that "sex, drugs and rock n' roll" had regressed to "AIDS, crack and Madonna." There didn't seem to be any hope that I would get to live in as interesting times as my parents did, or that the Baby Boomers would ever relinquish their hold on popular culture.

The sixties' grip on the public imagination continued into the 90s. JFK assassination theories, culminating in Oliver Stone's film, drenched popular culture. When The Beatles' Anthology appeared in 1995, it was one of the last great television events of the pre-internet age. In every presidential election from 1992 to 2008, service in Vietnam (or its avoidance) was an issue in presidential elections. Much of the animus against Bill Clinton seems to have stemmed from the notion that he represented all the aspects of the sixties that conservatives despised. The culture wars waged bright and hot in the 1990s, and those battles were really a referendum on the social and cultural changes wrought by the 1960s.

It is with this in mind that I have been surprised to see the inevitable: the fading of the 1960s from popular consciousness. President Obama was a just a child at the time, and not a participant in those heady years, even if the very fact of his presidency was enabled by the changes of that time. Potential foreign policy entanglements are never criticized as the potential to be "another Vietnam." We have now fought plenty of other wars and have our own new quagmire in Afghanistan to worry about. The culture wars are not over, but recent events, such as sweeping acceptance of gay marriage, seem to show that the reactionary side is bound to face ultimate defeat in the culture wars. Recent anniversaries, like those of the JFK assassination and the Beatles coming to America, don't seem to have resonated very deeply. There is perhaps a sense that our times, which have witnessed international revolution, war, political polarization, and economic volatility, are plenty interesting enough.

Labels:

history,

politics,

popular culture,

sixties

Thursday, March 6, 2014

Vintage MTV Videos: Phil Collins, "Sussudio"

It's been far too long since I've added a new entry in my old series on MTV videos of the 80s. The urge to write about that topic has been inspired by recent shopping trips, where the songs of my childhood have been apparently reborn as inoffensive musical wallpaper.

In the realm of inoffensive musical wallpaper, Phil Collins is king. This is rather odd for a man who started his career as the drummer for Genesis, an avant-garde prog rock band that composed concept double albums like The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway. Back in that time Collins played drums on Brian Eno's Another Green World, art rock's peak in the polyester decade. In the 80s this arty musician, now middle-aged and balding, improbably became one of the world's biggest pop stars, a feat that would be completely impossible today.

His success was due primarily to his talent for composing catchy pop hooks (just check out Genesis' "That's All"), but secondarily, I would argue, because of his music videos. Even though he was not as charismatic as Prince, Michael Jackson, or Madonna, Collins had a kind of funny, goofy everyman charm. His videos revealed a man who didn't take himself too seriously, who was accessible. Case in point is "Sussudio," whose conceit is that Phil is fronting a bar band at some club. It perfectly encapsulates his "I'm just a regular guy who sings" persona. At the start his group sounds clunky and Phil seems resigned to a lukewarm crowd. That is until 1980s video magic kicks in, the same magic that allowed ZZ Top to turn a crummy clunker into a badass hot rod.

All of a sudden the formerly tepid band is swinging, and Phil's got a big horn section of guys in pristine white suits with the crowd grooving along. The song itself is a silly, stupid amalgamation of 1980s pop tropes, from the synthesized horns to the metronomic rhythm. It hurtles along nicely, so fast that you don't bother to ask the question "what the hell kind of word is Sussudio?"and your brain resigns itself to playing it on a permanent loop for the rest of the day.