Thursday, December 27, 2018

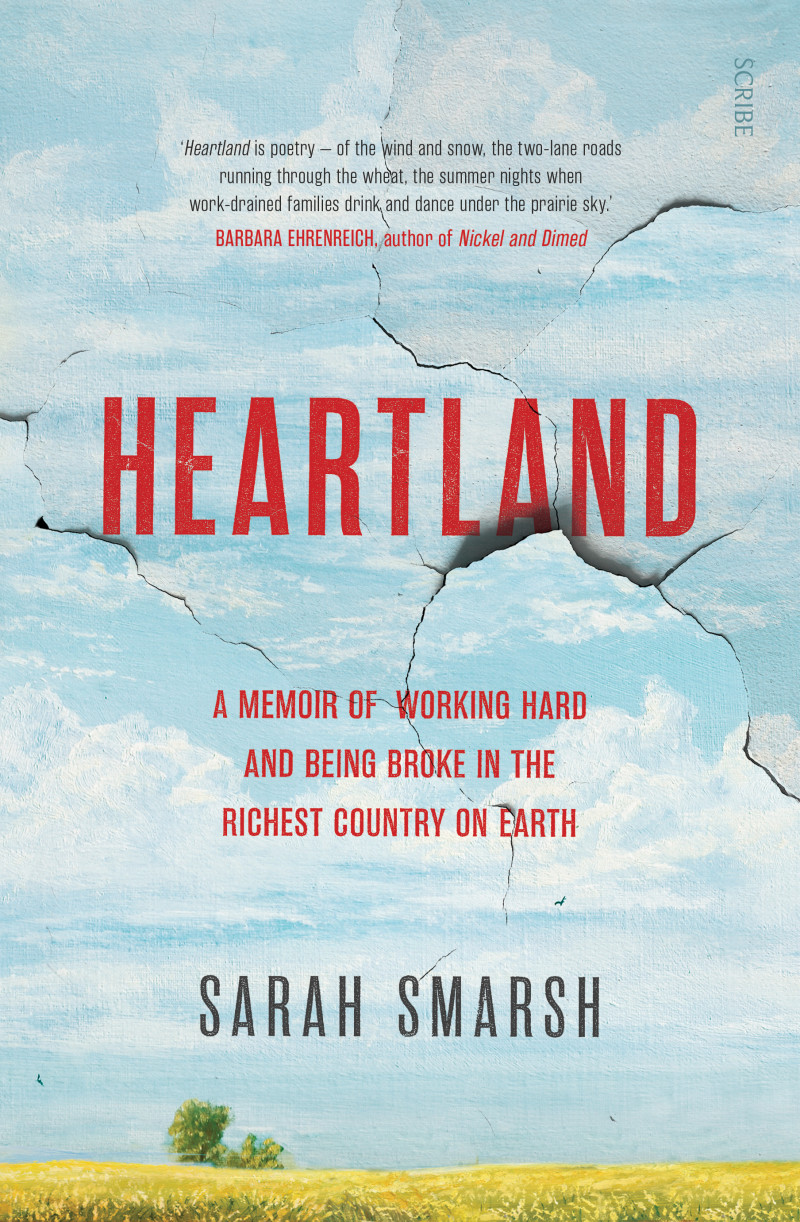

Thoughts On Sarah Smarsh's Heartland

I've just returned from a Christmas visit to my Nebraska homeland and on the way there and back got to read Sarah Smarsh's excellent book Heartland: A Memoir Of Working Hard And Being Broke In The Richest Country On Earth. As a fellow Great Plainsian raised in a rural German Catholic milieu with farming in my family the book was pretty much destined to find its way into my hands. Even closer to home, the author is from the same corner of Kansas where one of my sisters and her husband farm. He evidently once went to the same school as her, too.

The main difference in my experience and the author's is that she grew up poor in an unstable home environment, whereas I grew up lower-middle class in a very stable home environment. Unfortunately, families like mine tended to look down on families like hers in the never-ending quest for respectability. What's interesting about the book is that she explicitly connects her family's poverty to the broader social and political forces around their lives. Smarsh was born in 1980, and sees her life being profoundly shaped by the post-Reagan onslaught of neoliberalism. In her part of the world and mine the farm crisis of the 1980s came in like a wrecking ball. Once small farming ceased to be viable, it tore out the basic economic foundation of so many rural areas. Once her father could finally afford to buy a house in 2007, the housing bubble would burst and that house would become a millstone. This happened to countless other working class families.

Her main point is to use this more systemic understanding to undermine the cherished American idea that we are all the masters of our circumstances, and that simply through working hard we can get ahead. She shows in painful detail how hard her family members had to work throughout their lives, wrecking their bodies in the process. I fear that only people who understand that the American Dream mythology is a lie will actually read the book. Instead folks on the prairie will complain about people buying steak with food stamps and refuse to see how the government, from farm subsidies to backing inexpensive mortgages, has made their existence possible. (I heard plenty of this kind of talk on my trip home.)

This brings me to a question that the book touches on, but does not answer because it lies outside of the main thrust of the narrative: how did this political false consciousness take root in this community? Or is it even false consciousness? (For many folks "saving the unborn" to them is more important than whether they are voting for corporate plutocrats.)

It's a dynamic I've seen a lot in my own circle. My grandfathers, like Smarsh's, were staunch New Deal Democrats. Their children, and most of their grandchildren, are conservative Republicans. Not only that, the nature of conservatism in this region has radically changed in the past thirty years. My home area has always been conservative, but with a small "c." There was still support for public institutions, and guns were pretty non-controversial in my youth. Now schools and universities are being gutted as proposals are made to arm teachers. Kansas famously endured the misrule of Sam Brownback, whose libertarian tax policies have starved Kansas' public schools, once among the nation's best.

I don't have all of the answers either. As near as I can tell, it's a bitter stew of racial resentment, white nationalism, the radicalization of talk radio and Fox News, Boomer narcissism mediated through consumer capitalism, the rise of fundamentalist Christianity, and in how party identity has become closer tied to personal identity. (Being a Democrat marks you as one of "those people," essentially.) The next question that remains, of course, is if that any of the rural white conservatives out there can be swayed by a new economic populism from the left, or whether the aforementioned resentments and religiosity make that a fool's errand.

Another, more personal issue was on my mind as a I read the book, however. Smarsh talked about the difficulty of leaving the world she was brought up in, getting an education, and rubbing shoulders with people of privilege who have open contempt for "flyover country." This hit home for me because I have had to make the exact same transition. Unlike her, however, I have opted to leave for good, instead of to come back. I will get very defensive about my homeland when people around here in the New York area said dumb and ignorant things about it, but I am much more likely to rant against that homeland than Smarsh is. This balancing act is something that all internal exiles must face up to at some point. When I visited home this week I was glad to be there but also reminded that it's a place I could never live in anymore, from its awful politics to its bland food to its suffocating conformity. Standing beneath that all-encompassing, beautiful Plains sky does make my heart leap, but that's not enough for my anymore. Reading Heartland I wished I could feel the same closeness to that world I once felt. Maybe I'll get it back someday, or maybe I will just give up on trying to have it anymore.

No comments:

Post a Comment