Monday, August 28, 2017

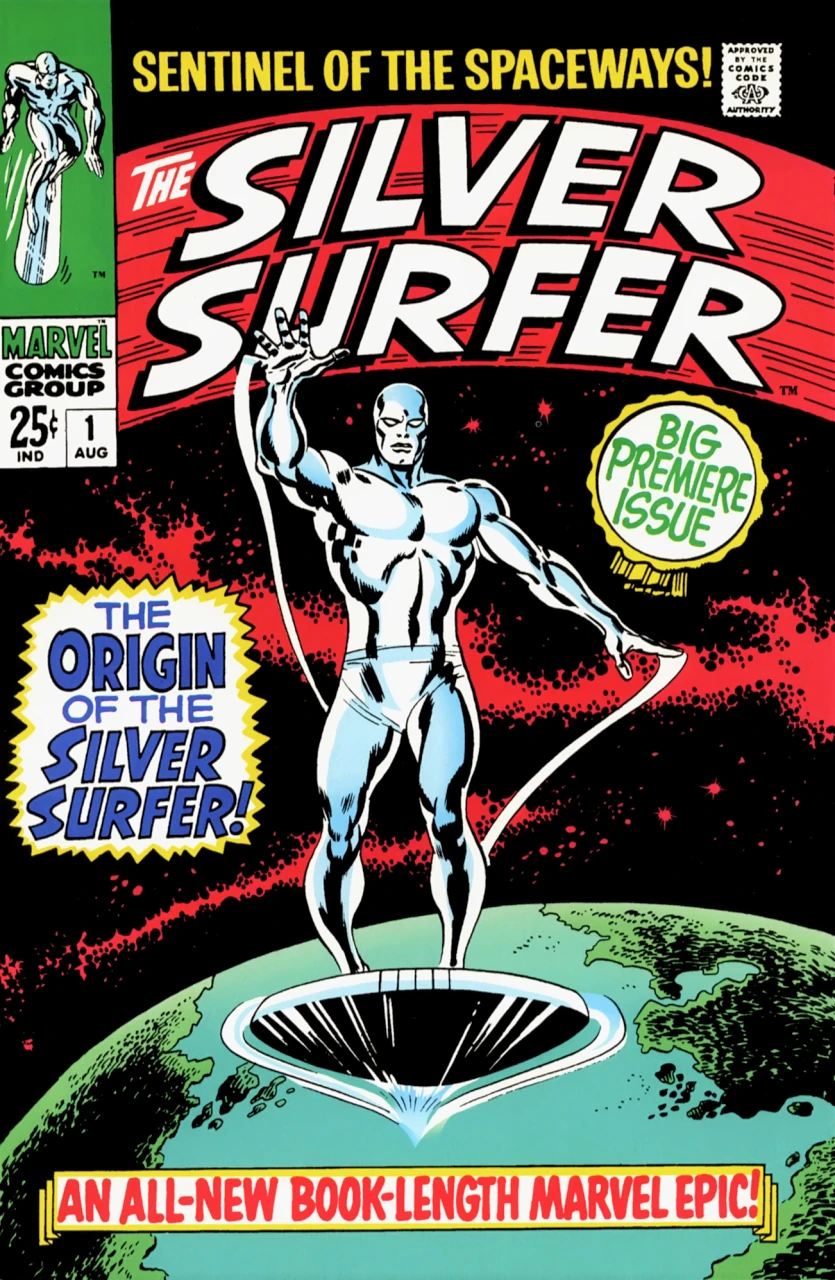

A Century Of Jack Kirby

I have some things to say about Houston, but I am going to let that wait. Instead, I'll just ask everyone to donate some money to the relief and rescue work going on right now.

Today I'd like to mark the centenary of Jacob Kurtzberg, better known to the world as Jack Kirby. His was a name I sort of knew, but I did not learn the true extent of his importance until very recently. Last year I got back into comics after a 25 year hiatus, and realized that they were exactly the escapist medium that my soul required to endure waking up in the morning frightened at living in a country falling into the abyss. I also started diving deep into the history of comics (one of my favorite things to read about), and then realized how much Jack Kirby meant.

It is hard for me to even summarize his accomplishments. He, along with Joe Simon, co-created Captain America in 1941, at the infancy of comics and before America had even gone to war. His famous first issue cover, showing Hitler getting punched, displayed the great kinetic nature of his art. If you look at other Golden Age stuff and then look at Kirby, the differences are impossible to miss. His art is just that much more exciting, and it set the template for what came later.

In the early 1960s he teamed up with Stan Lee to essentially create the Marvel universe, and had a hand in the origins of superheroes from Thor to Iron Man to Black Panther to the Hulk to the X-Men. He managed to create an huge array of iconic characters and "looks" in a very short period of time. With characters like Silver Surfer, he also added a new level humanity and emotion to superhero comics. After fighting with Lee he went to DC in the 1970s, where Kirby began his Fourth World universe, one of those things little known in the straight world, but idolized by comics fans. (You could even argue that he influenced George Lucas' notions of the Force.)

The fact that he created his magum opus a whole thirty years into his career is pretty amazing. Of course, part of the reason Kirby feuded with Stan Lee was that he was not compensated nearly what he was worth. This has to do the the comic book industry's work for hire structure, which did not give artists control over their creations. (That has changed somewhat at the independents, but is still an issue at the Big Two.) For that reason I consider him to be a patron saint of modern creatives, who are told that they can be paid with "exposure."

Movie theaters today are, for better or worse, dominated by characters created by Jack Kirby. This is an amazing thing considering that he was born into the immigrant slums of the 1920s Lower East Side, had little formal arts or literary education, and worked in an industry that for years treated their creations as disposable tripe. He helped make the medium meaningful, and in the process captured the imaginations of millions. Because he worked in a lowbrow medium that did not respect its artists, and was not a charismatic self-promoter a la Stan Lee, Jack Kirby is "the king" to comics geeks but unknown to the people who avidly pay to see his characters on the big screen. It's time that changed.

Friday, August 25, 2017

Memoirs Of A Lapsed Husker Fan, Part Two

Part one is here

Despite having my heart broken by the Huskers losing to the Sooners in November of 1987, my devotion to the team only increased. This is the kind of Stockholm Syndrome that most sports fans are familiar with. I still remember watching a big game as an adult with a group of friends, and as our team started losing and the curses and oaths started flying, a friend who was there to socialize and not as a fan simply asked "Aren't you supposed to like this?" to which another friend replied "Pleasure has nothing to do with it."

Like Job, the next few years would test me. In 1988 Nebraska lost early in the season to UCLA, giving up 41 points in a game where I spent a lot of time throwing a novelty foam brick that my sister had just bought at the screen. (After this game she declared the brick to be bad luck.) With national title hopes out of the way, however, the Huskers managed to go undefeated for the rest of the season. The best moment came at the end, when Nebraska beat Oklahoma on the road in Norman. The rain poured down, turning the astroturf into a slip n slide. Both defenses dominated, but Nebraska pulled out a win in a brutal slugfest, 7-3. It wasn't pretty, but it was the visiting fans in red that got to throw the oranges this time.

But then the Orange Bowl happened. Returning for the first time in five years, Nebraska had to play Miami again. The ghosts of the failed two point conversion haunted Huskerdom, and there was hope that the demons of Miami could be exorcised like those of Oklahoma. It was not to be. Miami won 23-3, but it might as well have been 63-3. They dominated the game, Nebraska never even threatened. This was the second bowl loss in a row, with five more to follow. This game was when the doubts began to be sowed in the minds of many a Husker fan. Was Osborne's running offense a relic of the past? Could Nebraska actually compete in recruiting with schools like Miami? Was the game passing Nebraska by?

The next season brought a new shock, namely the end of the old Big 8 order. For years it had been Nebraska and Oklahoma and six also rans. 1961 was the last time that neither team had won or tied for the championship. In the off season journalists and the NCAA uncovered a massive level of wrongdoing at Oklahoma, leading to the team getting put on probation for three years and Barry Switzer resigning. During the height of the War On Drugs it was especially damaging that Oklahoma players were using and dealing cocaine. For a Nebraska fan, this was vindication. We were good and moral, Oklahoma was degraded and evil, and they were now facing their reckoning.

While Oklahoma looked to be eclipsed for the forseeable future, the Colorado Buffaloes stepped into the breach. Their coach, Bill McCartney, had made defeating Nebraska the raison d'etre of his program. In 1986 the Buffs shocked the Huskers with an upset win, and he crowed that this was "our bowl game." (Remember, back then getting to a bowl game was actually difficult.) Nebraska had won in 1987 and 1988, but 1989 would be different. Colorado beat Nebraska, and looked confident in doing so. That was the hardest part to watch. The fact that they were running an option offense better than us was particularly galling. I still remember sitting on my aunt and uncle's shag carpet, the smell of tobacco and chili in the air, thinking that things were never going to be the same.

They weren't, for the Huskers or for me. I started high school in the fall of 1990, and my fall Saturdays were spent at marching band competitions and debate tournaments. This meant brining my Walkman along and stealing some time to listen on the radio in those pre-cellphone days. The Huskers played Colorado that season on the day of my very first debate tournament. A friend of the judge in one of my rounds sat in the room with us and listened to the game on his headphones, giving us updates on the score between speeches. This time around Colorado beat Nebraska on our own ground, and did it pretty handily. It seemed that McCartney had replaced Switzer as my chief tormentor. Things got worse when the Huskers traveled to play Oklahoma, and Husker quarterback Mickey Joseph broke his leg while being tackled out of bounds on the Oklahoma sideline. Rumors flew that it was a dirty Sooner player who pushed him into the bench.

The Sooners put up 45 points on Nebraska, as did their bowl opponent that year, Georgia Tech. Georgia freaking Tech! The Huskers finished the season ranked #24, barely in the top 25. 1991 had its high points, especially seeing former third stringer Keithen McCant rise to the top and do a capable job at quarterback. But this season also seemed to cement Nebraska's second rate status, and Colorado's ascendancy. The Huskers tied Colorado on the road, but should have won. The Buffs returned a blocked extra point for a safety, and the Huskers missed a game-winning field goal at the end, as snowballs rained down on the field thrown by Buffs fans. The refs did not call a penalty. Buffaloes fans were known for pelting Husker rooters with cups full of piss and snowballs with rocks inside of them. At least Oklahoma and Nebraska fans had a level of mutual respect in their rivalry, this was something else. Nebraska fans had always prided themselves on their decorum. There was a longstanding tradition that when the opposing team left the field at the end of home games, Husker fans would applaud them. The rivalry with Colorado brought out the worst, most soccer hooligan aspects of fandom.

The season ended cruelly, with another Orange Bowl against Miami. The Hurricanes were number one team in the country, the Huskers were merely a scrappy bunch happy to be there, and the 'Canes eviscerated them, winning 22-0. Getting shutout in a bowl game was pretty embarrassing, especially after four previous bowl losses, the last three lopsided. As I mentioned in the last installment, this game put me in a depression for about a week. I was a very lonely kid in high school, Nebraska football was one of my few escapes, and it had let me down. Even in my escapist pleasures I was a loser.

And then lo, in the off season, a star in the southeast led Tom Osborne to Bradenton, Florida, where he found Tommie Frazier, the chosen one destined to finally bring Nebraska to the Promised Land. Frazier was a quarterback with a cannon arm, strong legs, and the smarts to run Osborne's deceptively complicated offense. He managed to be recruited from Florida, home to the two teams -Florida State and Miami- that had been shellacking Nebraska on a yearly basis in bowl games. The new messiah was actually allowed to play starting quarterback as a freshman, something that the by the book Osborne never would have done in former times.

Even though the Huskers went 9-3 that season, which was not as good as their 9-2-1 the previous season, I could feel the winds of change. After an early hard loss on the road against Washington, the Huskers played with verve and fire. And then, on Halloween night, 1992, I experienced a level of schadenfreude that will never be topped in my life. Colorado came to Lincoln for an evening game, and Nebraska completely and utterly embarrassed the Buffaloes, winning 52-7. Frazier ran the offense to perfection, even pulling off a fumblerooski with the great lineman Will Shields. This would mark the beginning of nine straight wins against Colorado.

Of course, the Huskers still found a way to kill my buzz. They inexplicably lost on the road to Iowa State, a traditional doormat for Nebraska. I remember getting the news while at a debate tournament and assumed that I was being punked. Alas, it was true. While the Huskers still got to go to the coveted Orange Bowl, they had to face a powerhouse Florida State team. Nebraska was not blown out this time, but they looked overmatched, and never threatened to win. This was not a team that ever seemed capable of competing against the new powers of college football.

This is why what happened next year came as a complete surprise to me. Nebraska simply refused to lose. After a year under his belt, Frazier was even more competent. The defensive adjustments by coordinator Charlie McBride, criticized by Husker fans for being old-fashioned, starting paying off. He prioritized speed over power, turning defensive backs into linebackers and linebackers into defensive ends. The Blackshirts' blitz struck fear into the hearts of opposing quarterbacks. The season ended with a rematch, facing Florida State in the Orange Bowl, site of so much Husker misery. If Nebraska won this game, it would give them the national championship, their first real shot at the title in ten years.

Florida State had defeated Nebraska in bowl games after the 1987, 1989, and 1992 seasons. It felt like more of the same. It seemed like we didn't have a chance. This game also inflamed the Husker fan sense of self-righteousness like no other. The media said we didn't have a chance, and even seemed to dislike us, not giving the Cornhuskers the kind of scrappy underdog narrative that they would give other teams. Rather, they sneered and acted like Nebraska didn't actually belong there. What happened in the game only made things worse. It was a tense, low scoring affair, but late in the game some crucial officiating calls went against Nebraska, allowing FSU to score to go ahead late. With very little time left Frazier managed to get the team into field goal range for a winning shot, but the futile kicker line-drived his chance short of the goal posts. After the game FSU coach Bobby Bowden was gracious, saying that Nebraska had played the better game.

This was cold comfort. Nebraskans were anguished and enraged. A tee shirt making the rounds with a referee on a red background read "We Refuse To Be Screwed." A story circulated that Trev Alberts, an All-American linebacker who played the game with a cast on his right arm, was asked by referees to "take it easy" on Florida State quarterback Charlie Ward. (Alberts, a killer blitz artists, had sacked Ward three times.) Did this actually happen? Were those calls really botched? Did the national sports media actually dislike Nebraska? I do not have the objective standpoint necessary to answer those questions. All I can say that as a true devotee of the Husker religion my sect felt harried and persecuted.

The next year, 1994, would take all of that anger and resentment and turn it into a kind of righteous will to win. It also happened to be the year I started college, at Creighton University in Omaha. Although I had elected not to go to the University of Nebraska, I was still surrounded by Husker fandom. I also stayed with competitive debate, meaning that I was still having to find ways to keep up with the games in between arguing with other people while wearing a suit. One of the highlights of the season was going to a debate tournament at Colorado College, and breaking away to go to the student center to watch the Huskers manhandle the Buffaloes. Oh the glee I felt watching the Colorado fans squirm!

That game, however, came after a great deal of drama, the kind of drama that felt written by Hollywood. In the fourth game of the season, Frazier went down with a blood in his leg. This was shocking, not just for the season, but for how it threatened Touchdown Tommie's life. Remember, this was not long after Hank Gathers' death on the basketball court. It didn't help that there was a total bro on my debate team from Wyoming, Nebraska's opponent in their first game without Frazier. He would taunt me by holding his leg and saying "ooh, I got a blood clot." He also had sex with and then slut shamed a young woman I was in love with, so my dislike of this guy was off the charts. When backup Brook Berringer came in and led the Huskers to victory, I felt personally vindicated somehow.

Berringer would do a great job at quarterback, but more as a drop-back QB and less as an option quarterback. Unfortunately, he would suffer a collapsed lung during the next game against Oklahoma State, and Nebraska would be forced to call on Matt Turman, who would make his own Husker legend. Turman was an undersized walk-on from Wahoo, Nebraska. He looked so ridiculously small on the field, and had to start against a resurgent Kansas State team on the road. It was an ugly, rainy game that Nebraska won by riding its defense and its starting tailback, Lawrence Phillips, who would rush for over 1800 yards that season. (More on him later, obviously.)

Berringer came back, and the team never looked back. It was he who crushed number two ranked Colorado, humiliating them with one of my favorite all time Husker plays: a fake option then long bomb thrown for a touchdown. People had derided Nebraska' offense as slow and plodding and simple, but in that one play Berringer showed Tom Osborne's creativity and love of trickeration. I may have strayed from the Husker religion, but seeing that play has the same effect as playing "A Might Fortress Is Our God" for a Lutheran.

At one hour eleven minutes you can see the play that sums up Brook Berringer's brilliance in 1994

All of this lead to the bowl game. Once again, Nebraska was in the Orange Bowl. Once again, Nebraska was going to have to play Miami on their home turf. Like after the 1983 season, Nebraska was ranked number one and Miami number three. There is no way that a script writer could have conceived of such a situation. It was like something out of the movies. To make it even more theatrical, Tommie Frazier had recovered from his blood clot. Would he come in to play? This was a hard decision, considering how well Berringer had performed, and how high the stakes were for Frazier's health.

It was a fraught game for me personally, since I was not able to see it in Nebraska. I was at an international debate tournament being held at Princeton University. We arrived on January 1, game day. I wore my Husker gear out to dinner, and some waiter walked by me and said "Go Penn State." That year Penn State was also undefeated, and there was some controversy over the national championship, since there was no playoff or even championship bowl game. Nebraska was in the Orange as the Big 8 winner, Penn State in the Rose as the Big Ten winner, and nothing was going to change that. I saw the waiter's imprecation as a sign that I was in hostile territory. It also added to that prodigious Husker fan chip on my shoulder, which was inflamed by the thought that people in the rest of the country didn't like or respect my team.

Being 19, I could not watch the game in the hotel bar, and so watched it with two of my debate teammates in our hotel room. One of them was exhausted from New Year's Eve partying the night before, and when the Huskers fell behind, he decided to go to sleep and save himself the pain. The Huskers were down ten to nothing after the first quarter. Tommie Frazier started the game, but could not seem to do anything against the Miami defense. Osborne then brought in Berringer, who was able to hit some key passes and throw for a touchdown. Miami scored again, though, and Berringer also threw an interception in the endzone. That's the point when my friend went to bed, and the point that I thought that I was going to see yet another Nebraska embarrassment. I kept watching out of obligation, more than anything else.

Then, somehow someway, Nebraska's style of play, which I had lost faith in, was vindicated. McBride's aggressive blitzing paid off, as the Huskers sacked Miami quarterback Frank Costa in the endzone for a safety. Tommie Frazier came back into the game in the fourth quarter after Berringer's interception, and you could feel the game shifting. Nebraska had always prided itself on its offensive lines and their sturdy endurance. At the end of the game, Miami was wore out, and the dam broke loose in a very Husker way. Frazier moved the offense down the field, and they scored two touchdowns by running fullback Cory Schlesinger up the middle on a trap play. The 'Canes seemed powerless to stop the line's push, and caught flat-footed by the trickery. For a Husker fan it was as if the trumpets had sounded and the walls of Jericho had come crashing down. I could not believe my eyes.

My fandom has faded but I can't rewatch this game because the emotions are too strong

But neither touchdown was the most dramatic moment. After the first score, Osborne decided to go for two, to tie the score at 17. The ghosts of the 1984 Orange Bowl were hard to avoid, even if the stakes of this conversion were not as high. When Tommie Frazier connected on a pass to Eric Alford, I went nuts. It was a very similar play to the one in '84, but this time it worked! Turner Gill, who threw that pass back in '84, was on the sideline as Nebraska's quarterbacks coach. It was almost too perfect. I KNEW at the moment that there was no way that Nebraska was going to lose.

Alright, now I'm crying

Right after the game ended I got a knock on my hotel room door. It was one of my team's coaches, who had been watching the game in the bar. We jumped up and down and hooted and hollered. I was over a thousand miles away from home and wanted to be back there so bad. When our tournament was over and we went to the airport, I snagged the most recent Sports Illustrated, and basked in the victory, so long in coming. The national sports media seemed to actually be happy about Osborne finally winning. That chip on my shoulder suddenly shrank.

Little did I know that Nebraska would somehow better the 1994 season the next, or that the 1995 season would also begin my much more complicated relationship with my favorite team. More on that next time.

Wednesday, August 23, 2017

Memoirs Of A Lapsed Husker Fan, Part One

The game where I learned the truth about life

I do not think I will ever care about anything the way I once cared about the University of Nebraska Cornhuskers football. My absolute, fervent devotion to the Husker religion was such that when I finally got to go to a game at the age of 12 I considered it the highlight of my life up to that point. Four years later when they lost yet another bowl game in embarrassing fashion after a promising 1991 season, I fell into a depression for about a week.

Since then, things have changed. Like the lapsed Catholic who goes to mass only on Christmas and Easter, I have retained only a nominal membership in the Church of Husker. I will put no other football gods before it, but my connection is more a matter of identity and memory than any true devotion. Just as many of those at Christmas mass need assistance in reciting the Nicene Creed, I cannot tell you much about the team's starting lineup. At one time I could recite the entire roster down to the third string, now I can't even tell you who the starting quarterback is. Like Holy Week for Catholics, the beginning of the college football season is a heightened time for Husker fans, even the lapsed ones. Games start on Saturday, and every year, without me even trying, the memories of my Husker past will flood my mind.

Those who have never lived in Nebraska will have a hard time understanding the cultural significance that college football has in that state, and how much the Nebraskan identity is wrapped up in the university football squad. On gameday Memorial Stadium is the third largest city in the state, and every game has been sold out since 1962. In the 80s, at the height of shopping mall culture, they would pipe in radio play by play of games on Husker Saturdays over the PA instead of Muzak. I have been to many fall weddings in Nebraska where the attendees rushed out of the church to turn on their car radios and get the score.

Unlike in states like Texas and even Kansas, there is only one Division I team. Unlike Ohio and Michigan, there are no professional football teams. In fact, there are no pro teams in any sport whatsoever. In a sparsely populated and regionally diverse state that stretches almost 500 miles end to end, from the biggish city of Omaha in the east to the western rangelands of the Panhandle in the west, Cornhusker football has long been the state's one fixed commonality.

It was even more so in my youth. I was born and raised in Hastings, a town of 24,000 in south central Nebraska surrounded by farms. It also happens to be the hometown of Tom Osborne, and when I was a student visitors to the high school were treated to two giant Soviet cult of personality icons of Osborne in the front stairwell, one of him playing basketball, the other playing football. (He was throwing a ball in the latter picture, which was always the source of jokes considering Osborne's offensive philosophy.) The road from Hastings to nearby Grand Island was called Tom Osborne Expressway. All of this iconography was put in place well before he had even won a national championship.

Tom Osborne in his youth

I began my Husker fandom at a time when it seemed that a championship would never come. Not because of ineptitude like those sad sacks rooting for K-State, but due to the cruel whims of the football fates. In 1982 Nebraska went 12-1, winning the conference and the Orange Bowl against LSU. The one loss came against Penn State, and was enabled by a highly contentious pass interference penalty that Husker fans of a certain age will still grab your arm and bend your ear about. The whole off season all anyone seemed to talk about was how the refs cheated us out of a championship. (I was too young to follow the team in 1981, when it lost the national championship against Clemson in the Orange Bowl, another torturously just short of the line season.)

The following year in 1983 Nebraska had one of the most explosive offenses in the history of college football, blowing out the opposition en route to an undefeated regular season. Tailback Mike Rozier won the Heisman Trophy. Quarterback Turner Gill ran the option offense like a football magician. Wingback Irving Fryar would go first in the 1984 NFL draft. The season ended, however, with an infamous loss in the Orange Bowl against a rising Miami. After storming back from a halftime deficit, the Huskers scored a late touchdown, and could have tied the game with an extra point. If Nebraska had tied the game, the AP voters would still have elected the Huskers national champions.

At that point Tom Osborne, in a decision that was second-guessed more times than Napoleon's invasion of Russia, decided to go for two and the win. He thought that winning the national championship with a tie just wasn't honorable. The conversion failed, and the moment would replay itself in the minds of Husker fans for over a decade. While we wailed and gnashed our teeth, this decision also made Osborne into a Nebraska hero.

Nebraskans place an outsize emphasis on honesty and honor. In my experience, they tend to put a lot less stock in material "success" than people in other parts of the country. Cornhusker fans felt that winning "the right way" was the most important thing, and Osborne choosing an honorable loss over a cheap win made him the avatar of what many Nebraskans thought of as their best selves. That did not, however, dull the aching pain of a true gut punch loss. Rozier, Gill, and Fryar were all gone, and we all knew that it would be a long time before the planets would ever align like that again, if they ever did.

The next three seasons were full of frustration. Even though Nebraska had failed to win national championships after coming very close in 1981, 1982, and 1983, it had at least won the Big 8 conference and defeated hated rival Oklahoma. Back then the Nebraska-Oklahoma game was something like a high holiday, often scheduled the day after Thanksgiving. My abiding memory of those games is being at my aunt and uncle's house, the smell of my aunt's chili and uncle's pipe tobacco in the air. Both teams dominated the Big 8 conference, and the championship inevitably came down to this game every year. Fans of the winning team would throw oranges on the field, since in those days the winner of the conference automatically went to the Orange Bowl. (Stadium security was a lot less lax back then, too.) The sight of bright oranges flying through the chilly November air was always a surreal one, bringing happiness when tossed by Nebraska fans, and blinding rage when tossed by Sooner fans.

In 1984, 1985, and 1986, Nebraska lost to Oklahoma. This was not merely being defeated in a rivalry. For Nebraskans, this was a matter of good and evil. Tom Osborne was the ur-Nebraskan, quiet, steady, honest, doing things the "right way." Oklahoma was coached by Barry Switzer, the loud, brash, bootlegger's son whose program had been rung up for NCAA rules violations in the 1970s and who seemed like he would have shot his dog if it meant winning a championship. The most famous player on those teams was The Boz, Brian Bosworth, an even more brash athlete whose constant disrespect for authority somehow won him fame and adulation. There was nothing more dishonorable to a true Nebraskan than that.

I have never hated an athlete like I hated The Boz (glad to see in his 30 for 30 that he's gained some humility)

After three seasons of good but not great teams, the 1987 Cornhuskers suddenly seemed like the team of destiny. It was that year that I went to my first Husker game, against a Utah State team led by future Detroit Lions disappointment Scott Mitchell. Even though our seats were in the corner of the top row, probably the worst in the house, I had the time of my life. The Huskers returned two punts for touchdowns, and rushed for over 500 yards. Steve Taylor looked like the second coming of Turner Gill, running the option to perfection. In the next game, against UCLA, Taylor PASSED for five touchdowns. It seemed like there was nothing that could stop the Husker juggernaut from cutting through the Big 8 like a combine through a corn field.

Oklahoma was also undefeated that year, but before the big game was to happen, their quarterback Jamelle Holieway, a master of the wishbone offense who had led the Sooners to a national championship, got injured. He was replaced by a freshman, (something almost unheard of in those days) Charles Thompson. The Huskers had the Sooners at home that year. Broderick Thomas, future NFL linebacker and leader of the Blackshirts (the nickname for the Husker defense), had started a trend by proclaiming Memorial Stadium to be "Our House." (This led to some enterprising person making giant cardboard keys with the slogan printed on them that sold like hotcakes.) There was no way that we were going to lose.

Then, in what I thought was proof of the existence of God's grace, I was able to go to the game. My best friend Danny's father managed a local bank, meaning that he had the right connections to get tickets. We took the 100 mile trek to Lincoln with our dads on a brisk November day, but I spent the week before preparing my soul, as if I were about to go on pilgrimage. The local video stores starting renting tapes of Nebraska's glorious win over Oklahoma in 1971, the so-called "Game of the Century," which put the Huskers on the road to their last national championship. I watched that game multiple times, thrilling at Johnny Rodgers' amazing punt return, and Jeff Kinney just barely managing to stretch over the line for the winning touchdown. I believed with the belief that only a 12 year old sports fan could have that I was about to witness a similar moment of world historical importance.

Our seats were fantastic. My friend brought binoculars, and I was able to get a closeup view of the great Steve Taylor warming up before the game. In my eyes, he was invincible. Before the game my friend and I asked our dads if we could rush the field and help tear down the goal posts after Nebraska won, a statement that I should have understood to be a terrible jinx.

Neither team seemed able to get an edge until late in the first quarter, when Keith "End Zone" Jones busted loose for a 25 yard touchdown run. The Huskers went into the locker room at halftime up 7-0, and as he walked off the field Broderick Thomas led the crowd in the "Our House" chant. I have probably never been more innocently and naively happy in my entire life as I was in that moment. I say innocent because despite a constant stream of schoolyard bullying life had not yet taught me yet that pleasure is fleeting, that I should always expect the worst, and that disappointment is life's default setting. I first learned those truths in the second half of that football game.

Amazing that thirty years later I can watch this game on my computer

Nebraska never scored again. Oklahoma's offense moved down the field slowly but pitilessly. Every time their running backs got hit by a defender they seemed to fall forward for just enough extra yardage to keep the chains moving. It was like a kind of football crucifixion, a slow death. After grinding out a touchdown, Oklahoma scored a 65 yard touchdown on an outside run, making it 14-7. It might as well have been 70-7, since Oklahoma's defense shut Nebraska down and Steve Taylor threw three interceptions. In the fourth quarter I actually joined the other fans calling for Osborne to put in his more pass-happy backup, Clete Blakeman. In my anger and frustration I had, like some kind of football Judas turned on Steve Taylor, the player I was marveling over just a couple of hours before.

The game ended in darkness, literal and spiritual. Walking dejected from the stadium after the game, my friend Danny slammed his game program to the ground and gave it a swift kick down the street. We barely talked on the two hour ride back to Hastings. In a moment that every sports fan has at some point in their lives, I did not understand how something I loved so much could cause me so much pain.

[Editor's Note: Part two will soon follow, when I will discuss the seeming vindication of my love for my favorite sports team]

Tuesday, August 22, 2017

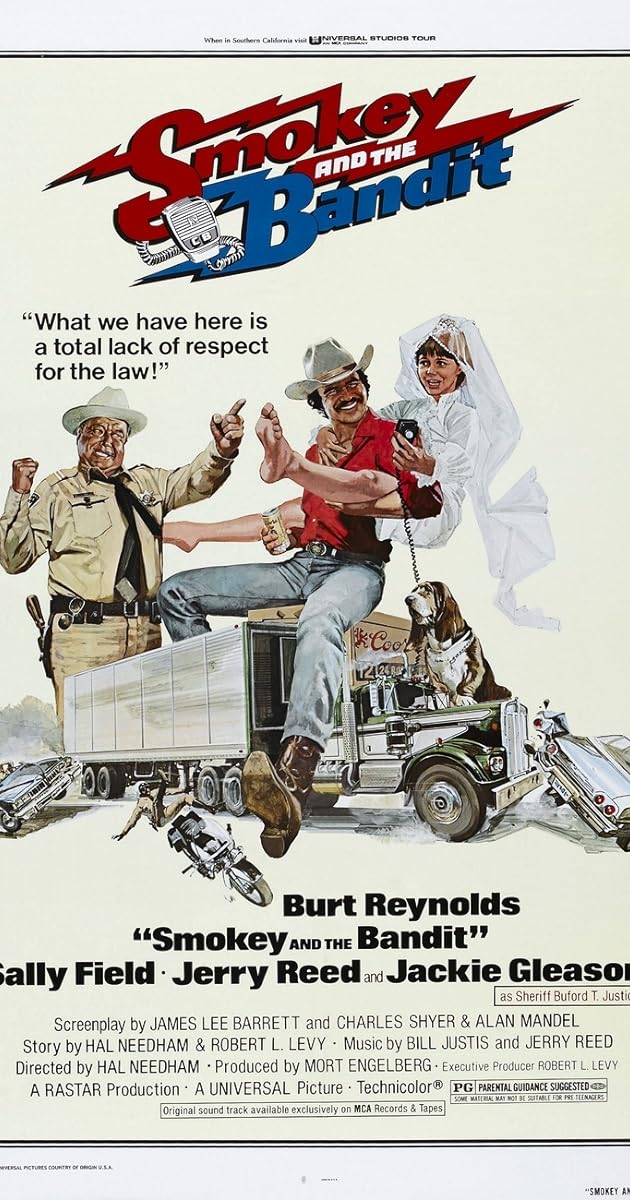

My Piece At Tropics Of Meta On Smokey And The Bandit

As loyal readers know, I am a contrarian in all things. This is why I am a Mets and White Sox and Everton fan. I just can't bring myself to embrace the bandwagon. So in a time when everyone is writing their hot takes about the political implications of the most recent blockbuster, I did my piece about a 40 year old trucker/car chase movie. At least the kind folks at Tropics of Meta were willing to publish it, and I am grateful for that.

I talk about how Smokey and the Bandit was an attempt to display a new, "post-racial" South to the country that had exorcised its demons, but had maintained its unique charms. Of course, recent events in Charlottesville and elsewhere show that the fraught racial history of the South, and the nation at large, refuses to be ignored.

Sunday, August 20, 2017

Episode 16 of Old Dad's Records

I just cut episode 16 of the Old Dad's Records Podcast. This time around I decided to make the theme prog rock, inspired by picking up Dave Weigel's The Show That Never Ends: The Rise And Fall Of Prog Rock. I've been reading lots of thick works of scholarship and long novels recently, it was good to burn through some brain candy. The book betrays the fact that Weigel is a reporter in his day job, meaning that there is a lot of information provided in a well-organized fashion but lacking broader commentary. I mean, if you're talking prog rock you've got to indulge yourself a little. (If you are into the topic it is still worth reading.)

Prog rock is a much-derided genre, and one that I avoided for years. However, I have learned to appreciate the musicianship, especially since I listen to a lot more jazz music than I once did. Also, I think it is important to listen to music that is "progressive," in that it is trying to advance the boundaries of art. If something fails, it should at least be an interesting failure.

In the podcast I talk about Styx's "Mr Roboto," and then do a full analysis of Genesis' Selling England By The Pound. After that I rave a bit about Sarah Shook & the Disarmers, a new and gutsy country band.

Wednesday, August 16, 2017

Media Talking Points From A Scholar Of Historical Memory

My dissertation was about historical memory, and I have written plenty of scholarship and taught classes about it. For that reason, it is extremely irritating to look at the discourse around the removal of Confederate monuments and not see any scholars of memory featured prominently in the media. Since I won't be asked to go on CNN, here are some handy talking points you can use in your conversations with other folks.

Monuments are about creating a "usable past."

Folks who are in the middle seem most convinced by the argument that taking down these monuments is somehow "denying history" or "eliminating history." It is easy to understand why this argument appeals to (white) people with a low-stakes interest in this issue, but it doesn't hold water. Monuments as part of public memory are an attempt to create a "usable past." They are a way to create an interpretation of the past that is given an official stamp of approval. This is why you don't see massive public monuments celebrating emancipation in this country, but plenty of them in Caribbean nations where the population is mostly black.

Confederate monuments created a white supremacist usable past.

Other people have written about this, but it bears repeating: the vast majority of Civil War monuments in the South were built during the height of Jim Crow. They were not immediate responses to the war. They are also intended to push a certain interpretation of the war, the "Lost Cause." This narrative essentially said that the white South was the superior side fighting for a just cause, and only lost due to the material superiority of the Union. These monuments defended the old slaveocracy at a time when lynchings and other incidents of racial violence were accelerating. By being erected after Reconstruction and during Jim Crow, they are not mourning a defeat in the Civil War, but actually celebrating the victory of white supremacy in its aftermath. Context matters.

There is plenty of precedent for tearing down monuments.

This is something we know, but it bears repeating. The same people today saying that tearing down Confederate monuments is "destroying history" did not complain when statues of Lenin and Stalin were eliminated during the revolutions in the Eastern Bloc. Those monuments were symbols of hated, repressive regimes. The same goes for Confederate monuments. They are the symbols of white supremacy. Hell, American colonists in New York famously tore down a statue of King George III, and melted it into cannon balls. This event was celebrated in my history textbooks in school. No one seems to be crying any tears over the loss of that statue. We are not bound to the usable pasts created by people who lived a hundred years ago.

We should view this moment as a time for positive change.

While it is good to tear down monuments to white supremacy, we should be thinking about the usable pasts of this country that would be preferable. For example, Union monuments built in the North were also built during a time of intense white supremacy. While these monuments obviously do not celebrate the defense of slavery, they rarely, if ever, mention it. This is due to the "reunionist" feeling at the time where the memory of the Civil War eliminated its political causes, and instead the reuniting of the country was emphasized. Of course, this meant erasing African Americans from this history, and essentially accept a reunited nation for white people only. In North and South we need more public memory of slavery, and the role of slavery in the Civil War. We should use this moment to create a usable past that is more inclusive and more honest about this country's history.

Sunday, August 13, 2017

What I Saw in Bedminster

Saturday morning I drove forty minutes out to rural western New Jersey to meet a group of people participating in the "People's Motorcade." This is a protest where protestors get around the lack of a nearby protest space by driving very slowly past the gates of Trump's golf course, their cars festooned with signs and noise blaring.

I had done it once before, back weeks before during the president's first visit. This time there were fewer cars, about twenty of them. Those participating were almost all from the immediate area, except for a family that, like me, had trekked from Essex County. This is a part of New Jersey that's rather conservative in its politics, especially compared to the rest of the state, so the locals really seemed to relish their event. It was begun by a single person, and is completely and totally grassroots.

In many ways this is a great thing. This kind of grassroots action is the necessary ingredient for successful political movements. However, I found it disheartening as well. Where was the institutional support? Why weren't larger groups coming in to bolster and support this? Since Trump has taken office there has been a massive tide of engagement by liberals and progressives, but the lack of institutional support and organization has made it difficult to sustain.

Our opponents do not make this mistake. Remember the Tea Party? It was astroturfed into relevance with massive infusions of conservative cash. It had a champion, Glenn Beck, on cable news spouting its talking points every day. We, on the other hand, are on our own.

This is why I am taking part in protests like the one I did yesterday. It's not only important as a political act, it is a reminder that I am not alone in this. Just standing there and chatting before we drove to the course was a kind of therapy. In a time when everything seems to be out of my hands, it felt like taking back some power. As I went past the entrance of Trump's golf course the first time I blared the Isley Brothers' "Fight The Power," on the second run it was Public Enemy. It felt good. Did it do anything? Not in the bigger picture, but it mattered for those of us who were there.

My good feeling died pretty quickly since right after I got home I started seeing the news out of Charlottesville. I'm still kind of reeling, to be honest. I only know that we have to get out there. We have to fight. If you ever wanted to know how you would have acted in in other times of moral crisis, now's the time to find out.

Thursday, August 10, 2017

August Dread

We put our daughters in camp this week and next, mostly because my wife's job starts up well before the school year. Last summer was her first in the new position and we didn't do this and I almost went nuts from having to wrangle two hyper and bored four year olds by myself for three weeks. This camp time has been nothing short of blissful. Today I sat on the back porch with a book and a cup of coffee, listening to Tusk as the leaves rustled in the gentle breeze. Earlier I started cranking out an essay for publication. In my relaxed state this week I had already written two others. I don't want these days to end.

But soon they will. For teachers August is the Sunday of months, a mix of relaxation and dread.

Those jerkoffs who always think teachers have their summers "off" never understand that our work is akin to being front line soldiers. Without leave we would lose our minds and the ability to keep fighting. Summer feels less like a break than a rotation out of the trenches. Like a World War I soldier, I am keenly aware when I am away that I will have to go back.

This is not meant to be a complaint. I love my current job more than any other job I've had. This year, as in the others, there were hugs and tears at graduation, and the kind of gratitude that warms my heart like nothing else. But getting to that point requires a truly monumental expense of mental, emotional, and physical energy. In my case I dread not the demands of teaching as much as my commute. It's an hour each way if everything goes right, which would be bad enough, but lately that hasn't been the case. Just getting to the train on time each morning requires a ritual of clockwork precision which includes walking the dog, preparing breakfast for my children, and getting a couple of headstrong toddlers out of bed and out the door before the sun comes up. I am usually worn out even before I get to my train, a train so crowded that half the time I do not even get to sit down.

Between my work, commute, and child care responsibilities on an average work day I get about two hours of free time if I am lucky. Some days it's none. I used to expand that time by staying up too late, but that had a lot of bad side effects, from fatigue to crankiness. Last year I resolved to get seven hours of sleep a night, and I mostly held to that. (Watching the World Series made that difficult, though.)

Soon the cycle will start all over again. As much as I am feeling the dread, I know that on that first day of class that I will answer the bell and will be full of energy and enthusiasm. At the end of the day, that's what you have to do if you want to be a teacher, and why so few people make it past their first few years, even with their "summer off."

Tuesday, August 8, 2017

Old Dad's Records Episode 15

This episode of Old Dad's Records is a "five" episode, meaning that I get to dissect one of my more prized records. In this case, it's Bruce Springsteen's Nebraska. With the president threatening nuclear war and tearing apart the social safety net, it seemed pretty appropriate.

https://soundcloud.com/jason-tebbe/old-dads-records-15-nebraska

Sunday, August 6, 2017

Life On Mars

Well, it's been six months since inauguration, meaning that we are only one eighth of the way through the first term of Trump's presidency. Every now and then I force myself to stop and look at what surrounds me and to remind myself the subtle changes that have already happened. We have already come to accept the fact that the leader of our country will go on Twitter to denounce his enemies, intimidate the press, and spew a torrent of lies and bullshit. That has become normal. Hell, it's become the daily entertainment for a lot of people. It reminds me of Kierkegaard's tale about a clown who rushes out to the stage of a theater to tell the crowd that the theater is on fire and they must leave. The crowd thinks it's a joke, and just laughs harder the more that the clown implores them, before it's too late.

We have made the destruction of our own democracy a kind of true life reality show. As I wrote about before, America went through a long Brezhnev period of rot, where the masses stopped actually believing in the system they were living under. I know more than one person who voted for Trump out of a kind of nihilistic glee. (At least one of them regrets it, but too late.) Even people who oppose Trump get fascinated by the show, forgetting the stakes involved. Back in the 2016 election, too many media voices treated him as a joke, and they still do. After all, they're not the ones getting deported, and it drives up their ratings and ad revenue. I get the feeling that Neil Postman's Amusing Ourselves To Death will be seen as a work of great prophecy by future generations.

And you what, I play my role in this. I watch Hayes and Maddow way too much. I spend a lot of time on Twitter. There is a difference between being engaged and being distracted, and I think I am becoming the latter. This morning I got a good reminder of that. I went to a nearby town to get some bakery bread, and there were folks setting up what looked like a protest in the small town square against Trump's immigration policies. At that moment I realized that while I had been diligently calling and writing lawmakers for the past three months, I had not been doing anything communal, not since I joined a protest for transgender rights in Austin, Texas, that I happened to run into back in March. That's not good enough.

Salvation is not going to come from anyone near the top. The top-level media still equivocates and still, after all these years, tries to play the false equivalency game. The Republican Party has signed a blood pact with the criminal in chief, and will not turn against him until maybe the 2020 election, if then. On the other side, if political smarts was TNT the Democrats could not blow their nose. Change is only going to come from those of us who take the time and make the sacrifices to act. That's a fact that I am going to try to keep in mind as the world around me becomes increasingly unbearable.

Thursday, August 3, 2017

Dialing Back

Let me give y'all a peek behind the curtain.

If have kept myself to a very strict pace of posting something every other day. I've been blogging at this pace for most of the past thirteen years. Back when I started, blogs were the cool new thing. Now they have been replaced by tweetstorms and articles on innumerable websites, from the big to the small. I have come to realize that my concentration on this blog has been spurred by a certain amount of cowardice. Here I am my own editor, here no one can reject my work. After years of the hell of the academic job market and publishing worlds, I am still very much afraid of rejection. I need to get over that.

Like the person who cleans their house when they need to be meeting a work deadline, this blog has allowed me to keep intellectually busy in a way that allows me to feel less guilt about my slacking in other areas. I have been working on a book length project for over six years, for example, where I have written over a hundred pages, but none in the past year. I have been able to get things published on much more renowned sites like Jacobin, but my pace of writing things for the outside has really slowed down.

It's not 2004 anymore, and very few people are reading blogs. Nobody is going to read this and decide to promote me out of the minor leagues. The fact of the matter is that deep down I am a plugger who still believes that excellent work is its own self-promotion. I am aware that in the current climate that is a phenomenally wrong-headed approach.

So I am going to still keep writing here, but I will be writing less for this blog and more for my other projects, which I will be doing more to integrate into this blog. I'm also going to keep up with the podcast, since that's been providing me with a direly needed creative outlet. And if you are a regular reader, please let me know what kind of stuff you prefer to hear from me, just so I know what to concentrate on. Thanks as always for listening.

Tuesday, August 1, 2017

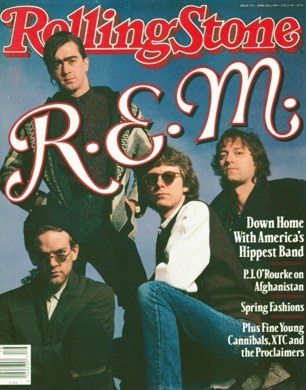

REM, "You Are The Everything"

1989, When the cover of the Rolling Stone mattered

Back when I was 15-16 years old, no band mattered more to me than REM. In my isolated Nebraska hometown they were pretty much the only band from the postpunk underground that I could hear on my local radio station and see on MTV outside of 120 Minutes until "Smells Like Teen Spirit" dropped like bomb in the late autumn of 1991.

During the preceding summer a great chunk of my summer job money went to buying the band's entire back catalog. Of all of their albums I purchased that summer, Green is perhaps my least favorite (though I still like it.) At that point in REM's career they had graduated out of the college rock circuit into the arenas due to "The One I Love" off their previous album and "Stand." Green was the last of a trilogy of more straight ahead rock albums (also including Life's Rich Pageant and Document), turning away from the stranger sounds on their early records.

The band would turn from the rock to folky and, ironically, greater fame with 1991's Out of Time and 1992's Automatic for the People. I call those the "mandolin albums" due to Peter Buck's infatuation with that instrument at the time. This missing link is a song on Green, "You Are The Everything."

It is one of my all time favorite REM deep cuts, and brings out an element of the band that always spoke to me: their rural vibe. Much was made of the fact that they hailed from and continued to live in Athens, Georgia, rather than the big city. The Gothic weirdness of rural America is embedded in their best music, and having grown up in a small town, that really grabbed me.

"You Are The Everything" starts with the sound of insects chirping in the dark, and I have always pictured the sound of my parents' back patio on a summer night whenever this song plays. There is an air of mystery in the haunting harmonium and mandolin. For lack of a better word, REM perfected the use of mystery in their music, of creating an uncanny feeling. Michael Stipe's poetic lyrics, never straight-forward and always open to interpretation, were a key element in this. In the early days he mumbled them, making it obvious that feel and impression, and not literal meaning, were what he was going for. By the late 80s the lyrics were easier to make out, but not always to interpret. This song expresses a kind of despair and fear, and has great evocative Stipe lines like "all you hear is time stand still in travel" and "eviscerate your memory." The "you" in the song is amorphous. Is he talking to his sister about a childhood road trip? A friend? A lover? Despite the talk of despair, there is warmth in the music and Stipe's voice. The talk of finding comfort and hope amidst the fear makes this song pretty apt for these times.