Saturday, May 31, 2014

Track of the Week: Allman Brothers Band, "Midnight Rider"

Summer's here and the time is right for listening to my favorite summer records. I don't know that it is, but some songs just sound so much better in the summertime. Perhaps my all-time favorite in this regard is "Midnight Rider" by the Allman Brothers Band, which is tailor-made for summer road trips. It was on one of these road trips that my deeper affection for "Midnight Rider" began. I was driving with my friends Debbie and Paul down to Augusta, Georgia, from Illinois. We were there for a wedding, and took the whole long trip in Debbie's tiny Toyota Tercel in a shade of teal not seen since the mid-90s, an appropriate ride for a troika of grad students.

It was quite a trip, driving through the flatlands of central Illinois, the eerie, verdant emptiness of southern Illinois' "little Egypt," over the scenic Tennessee mountains on down to Atlanta by way of Chattanooga. In the pretty drive across the north Georgia plains from Atlanta to Augusta, we put an Allman Brothers CD on, and staring out of the window at the tall trees wrapped in kudzu, there didn't seem to be a more perfect song in the world than "Midnight Rider."

Over the next few years it became a staple of mine on summer road trip mix CDs and playlists, both for the song's theme and for its almost perfect execution. The Allman Brothers had an amazing knack for having great musicianship without making it showy or ostentatious. The chops suit the song, including the laid-back yet masterful solo in the middle that somehow turns the feeling I get on a lazy drive on a country road into music.

Little did I know at the time "Midnight Rider" put its hooks in me that one of my other friends attending the wedding would get a job in the Allman Brothers' hometown of Macon, or later that he would show me the graves of band members Duane Allman and Berry Oakley. Life has its twists and turns, some good, some bad, but listening to those beloved summer records reminds me that there are a few small pleasures I can still count on in this world.

Thursday, May 29, 2014

Something Missing From The Elliot Rodger Discourse

As always happens after the all too common mass shootings in this country, there has been a national dialogue opened on a variety of issues, from gun control to misogyny. These conversations, especially those inspired by the #YesAllWomen hashtag have been revealing and important. However, there has been less discussion of the killer's racism, particularly on his animus against Asians. (Folks like Chauncey DeVega have been highly notable exceptions.)

This point was brought home to me yesterday at lunch where I was talking to a work colleague who is an immigrant from China. She had been following the story in the Chinese news, and was particularly alarmed that the killer had targeted Asian students, stabbing his three Chinese-American roommates to death. To her it was obvious that Rodgers' hatred of Asian-Americans motivated his actions as much as his misogyny, something that ought to be plain as day. After all, these were his first victims, and half of those who tragically died.

Sadly, they don't fit into the narrative that has been built around Rodger, which sees him solely as a shooter who targeted women. He certainly did shoot, and he certainly did target women, I don't dispute that, obviously, or that this event ought to prompt us to think deeply and seriously about sexism and gun laws. It should also, however, be just as important for us to discuss racism's role in all of this, specifically anti-Asian racism, and particularly how internalized racism can have violent consequences, considering that Rodger had an Asian mother. Perhaps this is because racism against Asians is rarely discussed in this country, or because of our country's typical hesitance to broach the subject of race when the dynamics are more complicated. (As Chauncey DeVega has written, a lot of folks just seem to be unable to understand how whiteness works or that race is a social construct.) In any case, it's a topic that ought to be getting more discussion in the current public discourse.

This point was brought home to me yesterday at lunch where I was talking to a work colleague who is an immigrant from China. She had been following the story in the Chinese news, and was particularly alarmed that the killer had targeted Asian students, stabbing his three Chinese-American roommates to death. To her it was obvious that Rodgers' hatred of Asian-Americans motivated his actions as much as his misogyny, something that ought to be plain as day. After all, these were his first victims, and half of those who tragically died.

Sadly, they don't fit into the narrative that has been built around Rodger, which sees him solely as a shooter who targeted women. He certainly did shoot, and he certainly did target women, I don't dispute that, obviously, or that this event ought to prompt us to think deeply and seriously about sexism and gun laws. It should also, however, be just as important for us to discuss racism's role in all of this, specifically anti-Asian racism, and particularly how internalized racism can have violent consequences, considering that Rodger had an Asian mother. Perhaps this is because racism against Asians is rarely discussed in this country, or because of our country's typical hesitance to broach the subject of race when the dynamics are more complicated. (As Chauncey DeVega has written, a lot of folks just seem to be unable to understand how whiteness works or that race is a social construct.) In any case, it's a topic that ought to be getting more discussion in the current public discourse.

Tuesday, May 27, 2014

Academia's Day Of Reckoning May Be Upon Us

Well, it looks like it might finally be happening. After decades of rising tuitions, rock climbing walls, and decreasing educational quality, the federal government is stepping in to give our universities a dose of the whuppin' stick. It will start rating schools based on a variety of factors, including student debt, tuition prices, graduation rates, and student earnings after graduation. Schools that perform poorly will see their funding cut. The DOE seems pretty confident in its ranking abilities, with one of its officials saying that it was no different than rating blenders. Look out, higher ed, you're about to get hit by tidal wave of the kind of standardization already laying waste to K-12 education.

That's because many facets of this proposal are repeating the failed "reform" strategies enacted there. By depriving money from "low-performing" schools, you effectively make it impossible to improve, since that costs money. By creating a ratings system based on imperfectly compiled quantitative data, everything important about education that can't be put on a spreadsheet (which is most of it) will simply be crushed into dust. If you don't believe me, up in Boston they are essentially eliminating history as the study of the past so as to better boost reading test scores. I can tell you now that the administrative fat cats who will have to come up with a response to this new policy will not respond by reducing administrative bloat, in fact I am sure they will hire more people to put in compliance regimes. To boost graduation statistics they will become more selective (i.e. classist) and encourage profs not to give failing grades. If you create major incentives based around pushing numbers around, people will find the easiest way to make that happen. The people who run the universities are master bullshit artists, so they will find a way to preserve the status quo as much as possible.

Despite the fact that I think this initiative by the Obama administration is a terrible idea, our university leaders brought it on themselves. They have spent the last few decades on a building spree and shoveling money into a metastasizing administrative layer while hiring an army of untenured adjuncts with (justifiably) little to no investment in the institutions where they teach. This means that students are not getting the optimal education, and scholars are not getting to reach their full potential. While universities are not to blame for the horrific cutbacks in higher education dollars at the state level, their inability to respond by cutting back on the building boom, big time college sports, and administrative bloat, along with their policy of just jacking up tuition (and presidents' salaries) instead of making the right cuts has led to this situation.

It's high time that the profession cleaned house internally in order to protect the people about to swamped by the quantified regime about to be put in place. Profs who aren't pulling their weight need a stern talking to from their peers, and to be told to either get their act together, or find another line of work. With higher ed in a crisis, everyone needs to be doing their job, if not they are letting everyone else down. It's also high time for students, parents, and faculty to hold the feet of administrators to the fire. When I was a professor I discovered a lot of student discontent with institutional priorities, discontent that could meaningfully be transformed into action. Administrators tend to exile faculty voice to powerless faculty senates; if the customers (that's how the university leaders see them) and their parents start to revolt, things will change. They need to change now, or else the change will soon be coming in the form of a one-size-fits all policy administered from the outside that will make the current troubles faced by the liberal arts look like a walk in the park.

That's because many facets of this proposal are repeating the failed "reform" strategies enacted there. By depriving money from "low-performing" schools, you effectively make it impossible to improve, since that costs money. By creating a ratings system based on imperfectly compiled quantitative data, everything important about education that can't be put on a spreadsheet (which is most of it) will simply be crushed into dust. If you don't believe me, up in Boston they are essentially eliminating history as the study of the past so as to better boost reading test scores. I can tell you now that the administrative fat cats who will have to come up with a response to this new policy will not respond by reducing administrative bloat, in fact I am sure they will hire more people to put in compliance regimes. To boost graduation statistics they will become more selective (i.e. classist) and encourage profs not to give failing grades. If you create major incentives based around pushing numbers around, people will find the easiest way to make that happen. The people who run the universities are master bullshit artists, so they will find a way to preserve the status quo as much as possible.

Despite the fact that I think this initiative by the Obama administration is a terrible idea, our university leaders brought it on themselves. They have spent the last few decades on a building spree and shoveling money into a metastasizing administrative layer while hiring an army of untenured adjuncts with (justifiably) little to no investment in the institutions where they teach. This means that students are not getting the optimal education, and scholars are not getting to reach their full potential. While universities are not to blame for the horrific cutbacks in higher education dollars at the state level, their inability to respond by cutting back on the building boom, big time college sports, and administrative bloat, along with their policy of just jacking up tuition (and presidents' salaries) instead of making the right cuts has led to this situation.

It's high time that the profession cleaned house internally in order to protect the people about to swamped by the quantified regime about to be put in place. Profs who aren't pulling their weight need a stern talking to from their peers, and to be told to either get their act together, or find another line of work. With higher ed in a crisis, everyone needs to be doing their job, if not they are letting everyone else down. It's also high time for students, parents, and faculty to hold the feet of administrators to the fire. When I was a professor I discovered a lot of student discontent with institutional priorities, discontent that could meaningfully be transformed into action. Administrators tend to exile faculty voice to powerless faculty senates; if the customers (that's how the university leaders see them) and their parents start to revolt, things will change. They need to change now, or else the change will soon be coming in the form of a one-size-fits all policy administered from the outside that will make the current troubles faced by the liberal arts look like a walk in the park.

Sunday, May 25, 2014

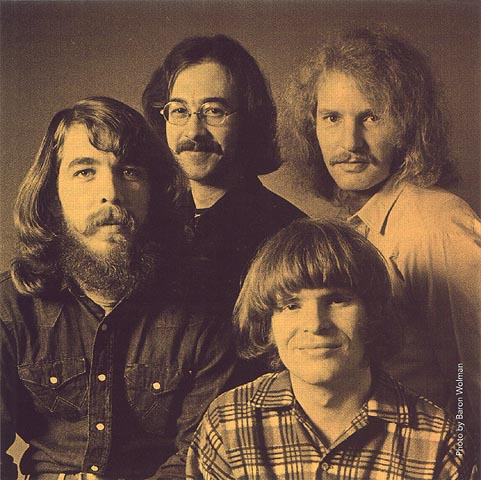

Track of the Week: Creedence Clearwater Revival "Ramble Tamble"

This Memorial Day weekend has been pretty rainy, but today we got a burst of unadulterated sunshine and blue skies here in the Garden State, as if to say that summer was indeed here. While cleaning up the house en familie I cranked up my summer music playlist, knowing that I can now more fully enjoy songs like "Ramble Tamble" by Creedence Clearwater Revival. It's a song bursting with jangly enthusiasm, pretty much how I feel in late May when school's almost out and the last of winter's chill has passed. (My moods are unusually in tune with the changing seasons.)

"Ramble Tamble" also happens to be a song that really took me by surprise the first time I heard it. I'd loved CCR from a young age, along with the Beatles, Monkees, and Motown they were my entree into the world of sixties music, a fine antidote to the dreck dominating the charts circa 1986. I knew them mostly as a singles band and only through compilations until one day I was trolling through the back of an antique store in Texas and found a copy of Cosmo's Factory on vinyl. I brought it home, dropped the needle, and out came "Ramble Tamble," a groovy, loud, exhilarating piece of rock greatness stretched out to seven minutes, well past the usual 2-3 minute length of CCR's many single.

The next day I talked to a musically-inclined friend like a religious convert, asking if he had heard the good news that is "Ramble Tamble." I just smiled wide and said "I KNOW!" with great enthusiasm. Usually when I find out, after many years, that a musical artist is not who I thought they were, it's negative. For example, I find my deep teenage love of The Doors a little embarrassing these days. In the case of CCR, I discovered that a great singles band could also sound like Velvet Underground if they had come from the swamp instead of New York City. "Ramble Tamble" will definitely be there this summer, as I drive down the highway on a road trip, grill some hot dogs, or sip an IPA on the back porch. I can't wait.

Saturday, May 24, 2014

Memorial Day Weekend Memories Of Valentine, Nebraska

Memorial Day weekend's meaning has faded quite a bit over the years. Nowadays it just happens to be a weekend when I have an extra day off, and that's about it. On Tuesday I'll go back to teaching school. When I was in the academic world, my school year was over already, so it was not all that momentous. Growing up, however, it was one of the most glorious times of the year.

Back home the last day of school was always the Friday before Memorial Day. As an adult I really don't have anything in my life like the last day of school, even though I'm a teacher. I just remember the feeling of absolute, complete freedom on that day with summer stretched out before me, and the knowledge that there would never be a day on the calendar when I was more free. This feeling was especially pronounced from the ages of 10-12, when I was old enough to able to go out and do things by myself or with friends, but still too young to have a summer job.

My family usually took to the great outdoors on Memorial Day weekend, and we started an important tradition when I was twelve years old. We drove up to Valentine, in the northern extremity of Nebraska, which became the location of most of our Memorial Day weekends for the following years. We had been there before one Labor Day weekend, but this time around we went canoeing on the Niobrara River for the first time. The Niobrara is not a wide or mighty river, but in the vicinity of Valentine it is absolutely beautiful and only a couple of feet deep, perfect for canoeing and inner-tubing. It cuts majestic cliffs into the sandy soil as it gently winds to the Missouri River. Three years ago I took my wife there for some kayaking, and I was amazed at the river's beauty and warmed by the peaceful feeling I still get while on its waters.

My first time was not so peaceful, since my mother and I tipped our canoe twice, both of us being inexperienced and me being the kind of kid so uncoordinated and lacking confidence in physical activity that I was always picked last in gym class. (My dad and sisters fared better in their canoe.) For the next few years I preferred to tube instead of canoe, which involves sitting on an inflated tractor tire inner tube with canvas stretched across the top of it. This means no steering, no tipping, and a lazy day soaking in the sun and taking in the sights. Once I got a little older, and more confident, I went back to the canoe. By that time we had started going to Valentine with two other families that we were close to, and the trip had become one of the highlights of my year.

After the first couple of trips we established a pretty regular routine, hitting each point along the way like Lenten penitent doing the stations of the cross. For that reason my memories of specific trips are rather blurry, but the regular elements are very vivid in my mind. The first thing to know is that the trip to Valentine involved moving from one world into another. I grew up in the town of Hastings, Nebraska, nestled in the heart of the fertile farm belt, full of corn and flat as a pancake. To get to Valentine meant crossing through the Sandhills, a much less stereotypical Nebraska landscape. The Sandhills are breathtaking in their emptiness, rolling from horizon to horizon under a limitless sky. Whenever I come home to Nebraska I make an attempt to at least drive to the outer fringes of the Sandhills, since there is no landscape quite like it anywhere else.

We often left for our trip on Friday afternoon, after my dad got off work. This meant loading up our 1984 Chevy conversion van, a massive beast of a vehicle with a sliding door and brown/beige interior that would be stocked to the gills with cans of soda and sunflower seeds, my Dad's preferred methods of staying awake on the road. (He doesn't drink coffee.) We typically drove up north to Grand Island and took state highway 2, perhaps the prettiest road in Nebraska, until we hit the Nebraska National Forest, right outside of the hamlet of Halsey. Once there we would have a picnic at the campground built by the Civilian Conservation Corps underneath the tall trees. The forest itself is an experience, located as it is amidst the barren Sandhills. Whenever I go there I feel almost as if I have landed on another planet, the groves of trees are that incongruous with the surrounding landscape. Until the fire tower got so rickety that they closed it down, we would take the stairs to the top, and look out on an emerald expanse of forest amidst the brown scrub of the Sandhills. It's a sight I'll never forget.

From there we drove to Valentine across the rolling hills, occasionally spying alkali lakes in the hollows, so ghostly in such a dry place. Valentine itself has only a couple thousand souls, but it is a metropolis by the standards of that region. It's the seat of Cherry County, so massive that it's the size of Rhode Island but home to fewer than six thousand people. My father, being the skin-flintiest man west of the Mississippi, always had us staying in a cheap motel with me sleeping on the floor in a sleeping bag, rather than springing for a rollaway bed. (My parents had one bed, my sisters another.) It's a living situation I endured for years of family road trips, but it has given me an ability to sleep easily on the floor, which served me well in my bohemian 20s.

The next day would be spent on the river, a leisurely few hours that ended with us driving back to the hotel via some beat up country gravel roads. In between we might stop at the wildlife refuge and see some buffalo. At night us kids (with our friends from the other families) would eat pizza ordered by our parents, play cards, and watch some HBO, something my dad sure as hell never sprung for back home. While we had a little party, our parents all went out of a bar and grill downtown called the Peppermill. I was always intrigued by this, since it was all part of an adult world that I wasn't able to participate in. When my wife and I returned to Valentine, I made sure to have a beer and steak at the Peppermill (now in a new location), just to be able to experience what I'd been missing out on that whole time.

The following day we'd go back home, usually stopping at one of the local natural wonders, like Snake River Falls, on the way, or in some cases make a stopover in North Platte and enjoy the water slide and go karts there. As I got older, I started to think I was too cool for these family trips and too dignified to sleep on the floor, and once I was in college, I let my family go on the trip without me (except for a memorable last hurrah before my senior year, when one of my college friends luckily happened to be in town at the same time.) Once my adolescent angst faded, my memories of these trips became more treasured with each passing year. Nowadays I only wish I can give my own children memories half as cherished when they get older.

Back home the last day of school was always the Friday before Memorial Day. As an adult I really don't have anything in my life like the last day of school, even though I'm a teacher. I just remember the feeling of absolute, complete freedom on that day with summer stretched out before me, and the knowledge that there would never be a day on the calendar when I was more free. This feeling was especially pronounced from the ages of 10-12, when I was old enough to able to go out and do things by myself or with friends, but still too young to have a summer job.

My family usually took to the great outdoors on Memorial Day weekend, and we started an important tradition when I was twelve years old. We drove up to Valentine, in the northern extremity of Nebraska, which became the location of most of our Memorial Day weekends for the following years. We had been there before one Labor Day weekend, but this time around we went canoeing on the Niobrara River for the first time. The Niobrara is not a wide or mighty river, but in the vicinity of Valentine it is absolutely beautiful and only a couple of feet deep, perfect for canoeing and inner-tubing. It cuts majestic cliffs into the sandy soil as it gently winds to the Missouri River. Three years ago I took my wife there for some kayaking, and I was amazed at the river's beauty and warmed by the peaceful feeling I still get while on its waters.

My first time was not so peaceful, since my mother and I tipped our canoe twice, both of us being inexperienced and me being the kind of kid so uncoordinated and lacking confidence in physical activity that I was always picked last in gym class. (My dad and sisters fared better in their canoe.) For the next few years I preferred to tube instead of canoe, which involves sitting on an inflated tractor tire inner tube with canvas stretched across the top of it. This means no steering, no tipping, and a lazy day soaking in the sun and taking in the sights. Once I got a little older, and more confident, I went back to the canoe. By that time we had started going to Valentine with two other families that we were close to, and the trip had become one of the highlights of my year.

After the first couple of trips we established a pretty regular routine, hitting each point along the way like Lenten penitent doing the stations of the cross. For that reason my memories of specific trips are rather blurry, but the regular elements are very vivid in my mind. The first thing to know is that the trip to Valentine involved moving from one world into another. I grew up in the town of Hastings, Nebraska, nestled in the heart of the fertile farm belt, full of corn and flat as a pancake. To get to Valentine meant crossing through the Sandhills, a much less stereotypical Nebraska landscape. The Sandhills are breathtaking in their emptiness, rolling from horizon to horizon under a limitless sky. Whenever I come home to Nebraska I make an attempt to at least drive to the outer fringes of the Sandhills, since there is no landscape quite like it anywhere else.

We often left for our trip on Friday afternoon, after my dad got off work. This meant loading up our 1984 Chevy conversion van, a massive beast of a vehicle with a sliding door and brown/beige interior that would be stocked to the gills with cans of soda and sunflower seeds, my Dad's preferred methods of staying awake on the road. (He doesn't drink coffee.) We typically drove up north to Grand Island and took state highway 2, perhaps the prettiest road in Nebraska, until we hit the Nebraska National Forest, right outside of the hamlet of Halsey. Once there we would have a picnic at the campground built by the Civilian Conservation Corps underneath the tall trees. The forest itself is an experience, located as it is amidst the barren Sandhills. Whenever I go there I feel almost as if I have landed on another planet, the groves of trees are that incongruous with the surrounding landscape. Until the fire tower got so rickety that they closed it down, we would take the stairs to the top, and look out on an emerald expanse of forest amidst the brown scrub of the Sandhills. It's a sight I'll never forget.

From there we drove to Valentine across the rolling hills, occasionally spying alkali lakes in the hollows, so ghostly in such a dry place. Valentine itself has only a couple thousand souls, but it is a metropolis by the standards of that region. It's the seat of Cherry County, so massive that it's the size of Rhode Island but home to fewer than six thousand people. My father, being the skin-flintiest man west of the Mississippi, always had us staying in a cheap motel with me sleeping on the floor in a sleeping bag, rather than springing for a rollaway bed. (My parents had one bed, my sisters another.) It's a living situation I endured for years of family road trips, but it has given me an ability to sleep easily on the floor, which served me well in my bohemian 20s.

The next day would be spent on the river, a leisurely few hours that ended with us driving back to the hotel via some beat up country gravel roads. In between we might stop at the wildlife refuge and see some buffalo. At night us kids (with our friends from the other families) would eat pizza ordered by our parents, play cards, and watch some HBO, something my dad sure as hell never sprung for back home. While we had a little party, our parents all went out of a bar and grill downtown called the Peppermill. I was always intrigued by this, since it was all part of an adult world that I wasn't able to participate in. When my wife and I returned to Valentine, I made sure to have a beer and steak at the Peppermill (now in a new location), just to be able to experience what I'd been missing out on that whole time.

The following day we'd go back home, usually stopping at one of the local natural wonders, like Snake River Falls, on the way, or in some cases make a stopover in North Platte and enjoy the water slide and go karts there. As I got older, I started to think I was too cool for these family trips and too dignified to sleep on the floor, and once I was in college, I let my family go on the trip without me (except for a memorable last hurrah before my senior year, when one of my college friends luckily happened to be in town at the same time.) Once my adolescent angst faded, my memories of these trips became more treasured with each passing year. Nowadays I only wish I can give my own children memories half as cherished when they get older.

Wednesday, May 21, 2014

Nebraska, The Pipeline, And Red State Progressives

I haven't been writing much about politics recently because I don't really see much of a point. Antarctica's ice is crashing into the sea with potentially catastrophic consequences and the party that looks primed to control Congress acts as if the facts of climate change are somehow in dispute. I have taken to shrugging my shoulders and wondering what the point is. That's even the case locally, where the Essex County Democratic machine (led by Joe DiVincenzo) has stood behind Chris Christie, even though he's a Republican, mostly to keep the graft and patronage flowing.

However, I did see an article this weekend that gave me hope. It's about Jane Kleeb, a Nebraska progressive living in my hometown of Hastings who has been organizing locals against the XL pipeline. Nebraska has not been too friendly to progressive causes in recent years. My home state has always been conservative, but recently when I've visited it seems to have been sliding into whacko conservatism. Towns like Fremont have been passing anti-immigrant laws, the governor has pushed a massively regressive taxation policy, and half the folks living in rural Nebraska's aging towns talk as if they've been spending their idle hours glued to Fox News.

It was not always thus. In my youth Nebraska was conservative, but it was a state that supported its public institutions, and its old populist suspicion of corporate power still held strong. I have felt like the land of my birth has become foreign to me, but maybe the current Tea Party resurgence is actually an aberration, mostly because it has led to some not very populist outcomes. ALEC-style corporate shenanigans don't go down well in a state distrustful of outsiders and big shots. TransCanada, as the article points out, has been strong-arming ranchers and farmers, people who are used to doing business based on trust, and who massively resent those messing around with their property, be it the government or a corporation. If the pipeline should break, which we can practically assume will happen at some point, it could very well pollute the Ogallala Aquifer, the water resource the state's farmers depend on.

The GOP has been pushing a cookie-cutter, one size fits all approach to state-level governance: austerity, erosion of labor rights, regressive taxation, and corporate giveaways. In the case of the pipeline, that corporate power uber alles approach might be backfiring. The modern Republican party is fundamentally ideological, it has become a mere vehicle for the conservative movement. Ideologues are typically incapable of adjusting their precious theology to human conditions on the ground, and that's where red state progressives can make some headway. This has already been happening in Kentucky, where the Republican ideologues calling for Obamacare's repeal have to contend with the fact that the state's management of the program has been very popular. Having health care trumps empty words and free market religion. In Nebraska protecting the interests of farmers will inevitably be more popular than promoting the bottom line of a foreign corporation.

Of course, many voters are yellow dog Republicans, so it might be extremely hard to get their vote. Red state progressives also have to steer clear of issues like abortion and guns, and progressives in other parts of the country are going to have to be understanding of that fact. All that said, I am quietly confident that the conservative gambit to completely take over red America may have drastically overplayed its hand. I can only hope.

Monday, May 19, 2014

Obi-Wan Kenobi, Existential Postmodernist Hero

In my opinion, it would also be good for filling in plot points unaddressed by the prequels, but which I greatly care about. Before the prequels came out, I assumed that Obi-Wan Kenobi's arc would be just as important as Annakin Skywalker's; I sort of figured that the three films would play out as a the story of their tangled relationship. Instead, Skywalker is a little tot when they meet, and their relationship seems rather shallow. Their lightsaber duel on the lava planet was epic, and Obi-Wan's bitter words for the burned up, defeated Skywalker provided maybe the one moment of true goosebumps in all of the prequels. However, I had thought that this would come at the end of the second movie, and the third would be an adventure where Obi-Wan had to figure out how to protect the Skywalker twins while living with the horrible guilt of seeing his Jedi friends hunted down and murdered by the very man he had trained. Instead that whole story is tossed off in about five minutes at the end of the third prequel. I'd really love to see a Star Wars film about Obi-Wan's struggle to survive the Jedi massacres and come to grips with his own responsibility via his failure to keep Anakin on the right path.

From the earliest days I watched Star Wars flicks, I thought Kenobi was an extremely compelling and complex character. In many respects he was a broken man, a once great person reduced to being a hermit on an isolated planet. He obviously carried around a great deal of personal guilt, evident when he admits to Luke that he thought he could train his father as well as Yoda, and was wrong. (He is still feeling this guilt in the afterlife!) After all, his failure contributed to the destruction of the Jedi and the Old Republic. He then had to spend years, alone, thinking about this. I can't imagine what that does to a man's soul.

In the end, however, he redeems himself. He manages to introduce Luke to the Force before sacrificing himself to save Luke's life. He guides Luke to Yoda, and gives him the strength to confront the man he now knows is his own father. For some reason, George Lucas became obsessed with making the Star Wars films into the redemption story of Darth Vader, when it is Obi-Wan who has a much more interesting path to redemption. He is not some kind of prodigy or chosen one, he is a person who made bad decisions out of good intentions, and has to live with the pain and suffering those decisions have caused. That's something a lot of us can relate to.

Perhaps it is this experience that makes him a bit of a moral relativist, especially for a supposedly pure Jedi. For example, he tells Luke that Vader killed his father, and when Luke comes back to Dagobah to confront him, Kenobi tells him that what he had said before was true, "from a certain point of view." He goes further, and explains that "many of the truths that we cling to depend upon our point of view." Kenobi also chides Anakin during their duel, rebuking him by saying "only Sith deal in absolutes." He has a remarkably postmodern perspective, considering the binary good vs. evil story told in the Star Wars films. That perspective makes Kenobi much more relatable to us than any of the other Jedi.

What kinds of films about Obi-Wan from the time of Darth Vader's creation until his first meeting with Luke could be made? How about My Dinner With Yoda, which follows a two-hour philosophical conversation between Kenobi and Yoda in the latter's Dagobah hovel? Like the characters in My Dinner With Andre, they are on hard times, and are trying to figure out what life is all about. Or perhaps the film could be Old Ben, a character study where Kenobi is known as the eccentric old man of Anchorhead while hiding his secret past that he must confront. I know this all sounds silly, but if Disney is going to produce a film in the Star Wars universe every year, why not go for broke? Why not make something arty? At the very least, why not feature the character whose damaged soul most resembles our own?

Saturday, May 17, 2014

Track Of The Week: Eddie and the Hod Rods, "Do Anything You Wanna To Do"

Three years ago this week I accepted my current high school teaching job, leaving behind my academic career. It was a heady time, and as usual for me, I incorporated music into it. For example, when I left my old town for Jersey, I cued up "Thunder Road" by Bruce Springsteen as my car hit the city limits, and had a big old grin on my face when the Boss cried "It's a town full of losers/ I'm pulling out of here to win."

Another important song for me in that moment was much more obscure, "Do Anything You Wanna Do," by 70s English pub rockers Eddie and the Hot Rods. I'd first heard of the group years before as a punching bag for John Lydon nee Rotten, who attacked them as poseurs jumping on the punk bandwagon. That impression changed in the late 90s, when I picked up a Rhino comp of 70s British new wave, and "Do Anything You Wanna Do" put its hooks in me.

The band and the song are hard to categorize, especially since the "pub rock" scene that spawned them shared punk's DIY ethos, but involved a certain reverence for the very old rocknroll and R&B idols that punk sought to smash. Eddie and the Hot Rods are not punk rock, but you can't really blame the Rods for that, since they never claimed to be such. (After all, it's not their fault if other people wanted to lump them into that category.) "Do Anything You Wanna Do" nevertheless has a fast tempo and rocks hard. Instead of punk's spittle and spite, however, the song contains an earnest message of everyday defiance. The singer says he's "tired of doing day jobs/ with no thanks for that I do/ I'm sure I must be someone/ Now I'm gonna find out who." It's a song about about telling your boss off, leaving your crummy town, and going off to find yourself. I used to drive around with this song cranked on my car stereo, and sing along in my own tuneless warble.

As much as I loved it as a 35-year old, I can't think of a better song this side of Alice Cooper that better encapsulates what it's like to be 18 and itching to finally live your own life. It's also been twenty years since my high school graduation, and while I didn't know this song yet, it pretty much nails how I felt at the time. In an ideal world, this song would be played at graduations all over the country this month, not the usual treacly crap.

Thursday, May 15, 2014

Remember: An Academic Job Is Just A Job

Three years ago this week I got offered my current job teaching at an independent high school in New York City. From the moment I stepped foot in the place, I knew it would be a great fit and a great place to work. (Thankfully my first impression has proven to be correct.) Taking that job meant leaving my academic job on the tenure track, a job I had fought long and hard to get, enduring two years in VAP purgatory and three nerve-fraying shots at the job market.

Back then I saw an academic job as a kind of Holy Grail, an almost divine object that would lift me up into the comforting bosom of academia's inner circle. I happily envisioned the years ahead, when I would be able to craft a second project that would make me a name in my field, where I would be a known fixture on campus, where I would eventually possess the knighthood of tenure and other delights. I made a cardinal mistake that so many others have fallen prey to: I failed to remember that an academic job is just that, a job.

In another line of work one would more quickly question going through seven years of intense schooling followed by two years in the contingent trenches only to secure a low-paid, high-workload position in a backwater hostile to academics and working in a dysfunctional department and commonly subject to the cruel whims of capricious colleagues and administrators. I was supposed to feel grateful at this turn of events because "at least you have a job." On top of everything, I was living a thousand miles from my spouse and going crazy. My academic dream had turned into a nightmare.

At some point, I don't know when, I had the epiphany that an academic job is just a job like any other job. If your job is ruining your life, it's time to find another one. A job is not worth sacrificing everything to. Your job does not define you, or give you worth, or give you integrity. It mostly gives you a paycheck, and everything else is just gravy.

There is an unhealthy and ultimately destructive tendency among academics to conflate one's job and one's life. (I'm hardly the first to say it.) The mantra goes like this: "I am doing what I love, so it's not really work. If I work 80 hours a week that's okay, since it's doing what I love and what defines me as a human being." This attitude is why you will often hear academics compete in the martyrdom sweepstakes in their conversations, each person bragging about how many hours they spent researching, how little sleep they had, how they don't have time for TV or pleasure reading, etc. This attitude is why spouses are expected, no questions asked, to relocate to isolated university towns where they will have no chance of finding employment in their fields. This attitude is why people who get paid a pittance compared to most other professionals will still work twelve hours a day without any pay increases for their labor. If you ever say no to anything, if you ever question the need to be working all day all the time, you'll be branded weak, unworthy, and somehow lacking in the fibre to do your job right.

It's all bullshit. A job is a job is a job is a job. It is big part of our lives, it should never be our life, unless you're a monk. Life is bigger than any job. I certainly love my job and put a lot of work and a huge chunk of my soul into it, but if my job turned sour (which I doubt it ever will), I'd leave for a better one, not tenaciously cling to it and call it "my precious!" a la Gollum. I had been brainwashed for so long, and been beholden so long to the norms of the profession, that it took me years to realize the error of my ways. I am glad I finally did, and I hope others do too.

Monday, May 12, 2014

What I Miss About Being A Professor

I have spent a lot of time on this blog talking about how I left academia and why I'm better off. Of that there can be no doubt. However, I have had some very powerful flashbacks recently that have deeply reminded me of what I liked about being a professor. Some of this was caused by recent conversations with academic friends, but also by my inexplicable decision to look up my published articles on JSTOR, which seem like they were written by a completely different person.

If anything, I miss being an expert and a researcher. I miss getting 19th century steamship guides from interlibrary loan and taking them back to my office and spending hours reading them. I miss having the time to do research, as limited as that time was with a 4/4 load and 160+ students a semester without a TA. I have tried to maintain my research agenda, but in the three years since leaving academia I have only managed to squeeze out two and a half chapters of a book project that will likely never see the light of day. Of course, more people will probably read this blog post than have read all of my articles combined, so it's not like I was ever some kind of meaningful scholar. This summer I do plan on being a little more productive on that front, though. I must say that it at least feels good to do research because I want to, not because I need tenure or a longer CV to take with me on the job market.

I also miss the resources and trappings of academia, like access to a research library and my own office. As a lowly teacher, I've got a desk and a bookshelf to myself, and that's it. I research at the New York Public Library, but that's different than having a library a few hundred feet from my office. I still remember the day I finally moved my books into my first, small office as a visiting assistant professor. I felt like I had finally "made it" and become someone.

At times I long for the flexibility of time that professors have. As a teacher, I probably work a few fewer hours per week then I did as a prof. However, I had a great deal of flexibility over how to use those hours, even at an institution that demanded ten office hours per week amidst a heavy teaching load. I never had classes on Friday afternoons, which I usually spent poring over research and writing articles at the local coffee house. It's different being a teacher. From 8:30 to 3:15 every single day, I have to be ON. It's a physically and mentally exhausting job, I normally pass out on the train on my ride home. We don't have summer "off," we have summer so that we are able to survive the next school year without dying or going insane.

Last and certainly not least, I miss the prestige. While administrators and politicians sometimes treat humanities professors at the enemy, there is probably no more besieged and denigrated profession today in America than teaching. I dread telling strangers what I do, lest they expound on their ignorant opinion of schools, displace their hostility for their own former on me, or act like I am some kind of layabout loser. ("I'd just love to be a teacher and get three months off" is something you should never say to me.) When I was a professor, revealing that information often meant that people treated me like someone special, even when I was a VAP. Now what I do is looked down on, not least by folks in academia.

I keep hearing people promoting post-academic careers saying things like "you can do more than 'just teach' with your PhD." That's right "just teach," as if shaping the minds of America's youth was some kind of piddly, useless job, as if all the work, care, and mental, physical, and spiritual labor it takes to reach teenagers is not all that meaningful or difficult to do. I'll let you in on a secret: teaching high school is harder than being a professor, at least on a day-to-day basis. Sure, I don't have to read antiquated sources in a second language and lead discussions of academic monographs with grad students, but those were all things that years and years of grad school had prepared me for. It is difficult to prepare for a room of engaged yet hyper teenagers going in a million directions at once. In fact, nothing can really prepare you for that. Anyone who says I "just teach" can just kiss my ass.

Make no mistake, I am a lot happier than I was before. I am living in a place where I actually want to live, I am with my beloved wife, I am getting paid more, I am treated as if I have value by my employer, and I am a father, something that might not have happened had I stayed in academia. It's not like I want to go back to being a prof, I think I've managed just to see it as an interesting job that didn't work for me, not a religious calling demanding infinite sacrifice, as so many seem to treat it.

If anything, I miss being an expert and a researcher. I miss getting 19th century steamship guides from interlibrary loan and taking them back to my office and spending hours reading them. I miss having the time to do research, as limited as that time was with a 4/4 load and 160+ students a semester without a TA. I have tried to maintain my research agenda, but in the three years since leaving academia I have only managed to squeeze out two and a half chapters of a book project that will likely never see the light of day. Of course, more people will probably read this blog post than have read all of my articles combined, so it's not like I was ever some kind of meaningful scholar. This summer I do plan on being a little more productive on that front, though. I must say that it at least feels good to do research because I want to, not because I need tenure or a longer CV to take with me on the job market.

I also miss the resources and trappings of academia, like access to a research library and my own office. As a lowly teacher, I've got a desk and a bookshelf to myself, and that's it. I research at the New York Public Library, but that's different than having a library a few hundred feet from my office. I still remember the day I finally moved my books into my first, small office as a visiting assistant professor. I felt like I had finally "made it" and become someone.

At times I long for the flexibility of time that professors have. As a teacher, I probably work a few fewer hours per week then I did as a prof. However, I had a great deal of flexibility over how to use those hours, even at an institution that demanded ten office hours per week amidst a heavy teaching load. I never had classes on Friday afternoons, which I usually spent poring over research and writing articles at the local coffee house. It's different being a teacher. From 8:30 to 3:15 every single day, I have to be ON. It's a physically and mentally exhausting job, I normally pass out on the train on my ride home. We don't have summer "off," we have summer so that we are able to survive the next school year without dying or going insane.

Last and certainly not least, I miss the prestige. While administrators and politicians sometimes treat humanities professors at the enemy, there is probably no more besieged and denigrated profession today in America than teaching. I dread telling strangers what I do, lest they expound on their ignorant opinion of schools, displace their hostility for their own former on me, or act like I am some kind of layabout loser. ("I'd just love to be a teacher and get three months off" is something you should never say to me.) When I was a professor, revealing that information often meant that people treated me like someone special, even when I was a VAP. Now what I do is looked down on, not least by folks in academia.

I keep hearing people promoting post-academic careers saying things like "you can do more than 'just teach' with your PhD." That's right "just teach," as if shaping the minds of America's youth was some kind of piddly, useless job, as if all the work, care, and mental, physical, and spiritual labor it takes to reach teenagers is not all that meaningful or difficult to do. I'll let you in on a secret: teaching high school is harder than being a professor, at least on a day-to-day basis. Sure, I don't have to read antiquated sources in a second language and lead discussions of academic monographs with grad students, but those were all things that years and years of grad school had prepared me for. It is difficult to prepare for a room of engaged yet hyper teenagers going in a million directions at once. In fact, nothing can really prepare you for that. Anyone who says I "just teach" can just kiss my ass.

Make no mistake, I am a lot happier than I was before. I am living in a place where I actually want to live, I am with my beloved wife, I am getting paid more, I am treated as if I have value by my employer, and I am a father, something that might not have happened had I stayed in academia. It's not like I want to go back to being a prof, I think I've managed just to see it as an interesting job that didn't work for me, not a religious calling demanding infinite sacrifice, as so many seem to treat it.

Sunday, May 11, 2014

Track of the Week: Ray Charles, "Mess Around"

Yesterday I was listening to WFMU, and that most blessed moment of grace occurred: the right song came on the radio at exactly the right moment without me anticipating it. That song is Ray Charles' "Mess Around," one of my personal favorites, and I song I associate with letting the good times roll.

At my local bar in Michigan, which was by far the best local bar I've ever had, there was a CD jukebox of impeccable quality, including a Ray Charles compilation. Practically every time I dropped in after work or on a sunny summer eve I would put some tunes on, and almost always play "Mess Around" by Ray Charles and "Cocaine Blues" as performed by Johnny Cash at Folsom Prison. The hours spent at that bar with my friends were absolutely therapeutic, and I remember them fondly.

The song is like nothing else in Charles' catalog due to its frenetic barrelhouse rush and New Orleans influence, and it never fails to bring a smile to my face. Not only is the piano an absolute joy, Charles' sax player, David "Fathead" Newman, probably laid down his sickest solo on this track. Every time the song is over I feel exhilarated, like I used to after sledding down a hill as a child. It's good to know I can still get that feeling without looking ridiculous trying to sled down a hill at my age.

Friday, May 9, 2014

Metal Video Mania

For some reason my head's been in the 1980s these last few weeks. In some ways in might be a kind of return of the repressed, since I tried so hard for so long to forget much of my early past. It is shocking to me when I view films and television from the time, and see the world presented being both so familiar and entirely foreign to me. No relic reminds of that gulf more than the music video, a touchstone of the time's youth culture which is practically meaningless today as a cultural force. Also, while heavy metal still lives, it is now far, far away from the mainstream, unlike in the 1980s. Just for kicks, here's a list of 80s metal videos worth watching.

Motley Crue, "Looks That Kill"

Someone seems to have watched one too many B-level post-apocalyptic movies. I am still sure how they managed to have all of those flaming torches around all of that hairspray.

Scorpions, "Rock You Like A Hurricane"

Ironically, it took metal gods from Germany to find the right tune to rock monster truck rallies all across America. This video might have more synchronized guitar rocking and musical grimaces for the camera per minute than any other in existence.

Dio, "Holy Diver"

There has perhaps never been any soul in existence more metal than Ronnie James Dio. This pint-sized wonder had more rocking in his pinky than most people have in their whole bodies. The video for this song looks like Dungeons and Dragons cosplay with guitars.

Accept, "Balls to the Wall"

Sludgy guitars: check. Simultaneous guitarist rocking: check. Demonically dwarfish frontman: check. Ridiculous song title: double check. 80s metal awesomeness: no doubt.

Autograph, "Turn Up The Radio"

Lasers. Robots. Catchy hooks. Still sucks, but my, what a cultural artifact.

Metallica, "One"

I was not into metal back in the day, but I loved this video. The plot and footage lifted from Johnny Got His Gun were darker and much more politically meaningful than just about anything out there on MTV. The lush, almost classical guitars at the start also made Metallica less threatening to me and millions of others before they really cashed in with the "black album" a few years later.

Wednesday, May 7, 2014

David Brooks, Ross Douthat, And Cultural Conservatism's Contradictions

Conservatives are always bemoaning the cultural fallout caused by the very political economy they so rabidly support, but never seem to make the connection. Case in point are recent columns by Ross Douthat and David Brooks on the culture of college students.

Douthat's piece discusses "party culture" on campus, wherein he highlights a study showing that affluent students at state universities benefit from a culture where they can be comfortably decadent and at the top of the social heap while working-class students find themselves isolated. Having worked on such campuses, I've seen this dynamic at work. However, Douthat does not see classism at work here, but the perniciousness of "cultural permissiveness." As we say back home in Nebraska, Douthat has it bass ackwards. The "permissiveness" by itself isn't what causes class disparities, it's the fact that party culture fits within a pre-existing class structure, a structure that Douthat would never question. He says we'd be better off with an upper class that maintained "bourgeois values" of "thrift, diligence, sobriety, and chastity."

Douthat and other cultural conservatives never seem to wonder whether the dearth of these values has anything to do with the increasing dominance of consumer capitalism over our society. Capitalism and the market care nothing for traditional values, in fact, they are the biggest forces against tradition in the world today. The fundamental contradiction between cultural conservatism's professed values and conservative support for unfettered capital also bedevils David Brooks' most recent column. He discusses how surveys of college freshmen show that they are much less interested in developing a philosophy of life than they used to be in the 1960s, and much more likely to see college education merely as a stepping stone to making money. That's certainly what I've seen in my time on campus, but Brooks is oddly silent on the causes of this cultural shift. He might be silent because the growing materialism among the youth reflects the ever-increasing hegemony of neoliberal economic thinking.

Brooks and Douthat love wagging their finger at what they consider the loss of traditional values, even though they support the biggest force for the destruction of tradition that the world has ever known: capitalism. In a lot of ways, I think this reflects a fundamental contradiction at the heart of modern conservatism, one that should not be allowed to continue unnoticed. Those who wish to destroy every human value except the cash nexus should not be allowed to stand in moral judgement over the rest of us.

Douthat's piece discusses "party culture" on campus, wherein he highlights a study showing that affluent students at state universities benefit from a culture where they can be comfortably decadent and at the top of the social heap while working-class students find themselves isolated. Having worked on such campuses, I've seen this dynamic at work. However, Douthat does not see classism at work here, but the perniciousness of "cultural permissiveness." As we say back home in Nebraska, Douthat has it bass ackwards. The "permissiveness" by itself isn't what causes class disparities, it's the fact that party culture fits within a pre-existing class structure, a structure that Douthat would never question. He says we'd be better off with an upper class that maintained "bourgeois values" of "thrift, diligence, sobriety, and chastity."

Douthat and other cultural conservatives never seem to wonder whether the dearth of these values has anything to do with the increasing dominance of consumer capitalism over our society. Capitalism and the market care nothing for traditional values, in fact, they are the biggest forces against tradition in the world today. The fundamental contradiction between cultural conservatism's professed values and conservative support for unfettered capital also bedevils David Brooks' most recent column. He discusses how surveys of college freshmen show that they are much less interested in developing a philosophy of life than they used to be in the 1960s, and much more likely to see college education merely as a stepping stone to making money. That's certainly what I've seen in my time on campus, but Brooks is oddly silent on the causes of this cultural shift. He might be silent because the growing materialism among the youth reflects the ever-increasing hegemony of neoliberal economic thinking.

Brooks and Douthat love wagging their finger at what they consider the loss of traditional values, even though they support the biggest force for the destruction of tradition that the world has ever known: capitalism. In a lot of ways, I think this reflects a fundamental contradiction at the heart of modern conservatism, one that should not be allowed to continue unnoticed. Those who wish to destroy every human value except the cash nexus should not be allowed to stand in moral judgement over the rest of us.

Monday, May 5, 2014

When Cross-Town Baseball in Chicago Mattered, And Why It Doesn't Now

Right now I am watching the first game of the inter league series between the Cubs and White Sox being played at Wrigley Field. I can distinctly see some empty seats, which never would have been the case fifteen years ago, even on a cold night such as this. The Cubs-Sox games used to have a kind of elevated, carnival atmosphere to them and an intensity one normally associates with the World Series. The house was packed, the fans went bananas, and some serious bragging rights were on the line.

Of all the interleague games, these were the craziest and the most meaningful. The Yankees-Mets rivalry, for instance, is not nearly so fraught. You will find fans of both teams in all parts of the Tri-State area, but the Yankees are so dominant that the Mets are the one team in the country that does not have a majority of fans in any zip code. Chicago, however, is different. Cubs vs. Sox is really about North Side versus South Side, with all of the class, cultural, and racial divisions that the geographic division implies. (Of course, there are plenty of working class Cubs fans and effete White Sox fans.)

Back when the crosstown series mattered, it was White Sox fans who approached it with particular fervor. The Cubs are Chicago's dominant team in terms of number of fans and media coverage, and their fans also tend to be more affluent. For many White Sox fans, beating the Cubs wasn't just a baseball victory, it was a rare victory in life against the larger forces that bear down on them on a daily basis. In fact, I would say that White Sox fans are much too concerned with the Cubs and getting revenge on them and what they stand for. I remember going to White Sox games in the aftermath of Sammy Sosa's corked bat controversy, and seeing mocking T-shirts for the "Sosa Cork Company" sold by vendors outside of the game. The Sox were playing well that year and in playoff contention, which made the focus on a National League team rather strange.

Since that time, however, the rivalry has dimmed. Some of this can probably be attributed to the fact that interleague play has lost its novelty. (Are you listening, Mr. Selig?) However, a lot of it has to do with the fortunes of the Cubs and Sox since their first crosstown series in 1997. Back then both teams were pretty lame. Sammy Sosa could sock the ball, but the Cubs only won 68 games that year, while the Sox finished just under .500 and their management had traded away veteran pitching in the infamous "White Flag Trade." It was the end of July, and the Sox were only 3.5 games out when management decided not to contend. Needless to say, that didn't exactly excite the fan base. With both teams not threatening to win the pennant, it's only natural that fans could channel their energy into a crosstown series.

That situation didn't last forever. In 1998 the Cubs won the wild card, and in 2000 the Sox won the division. The Cubs' postseason ordeal in 2003, exemplified by the Bartman Game, gave Cubs fans something much worse to rue about that losing a single regular-season interleague series. Then, two years later in 2005, the Sox won the World Series, something that mattered a whole helluva a lot more than who won in May or June between the two teams. The White Sox had finally won a championship for the first time since 1917, while the Cubs' last victory, in 1908, has now gone well past its centennial. Winning the Series has made most sane Sox fans drop their obsessive Cubs hatred (or at least mitigated it), and the Cubs' current problems are so deep that winning games against the South Siders is cold comfort. There was one last gasp of the old rivalry in 2006, when an aggressive play at the plate by AJ Pierzynski led to a benches-clearing brawl. Since then it's seemed like just another series, and that might not be such a bad thing.

Saturday, May 3, 2014

Track of the Week: Mudhoney, "Touch Me I'm Sick"

I've read a lot of books about music, and one that's stuck with me over the years is Michael Azerrad's Our Band Could Be Your Life, a history of 1980s underground rock told through profiles of its most important bands. I was too young and too distant from any musical underground in those years, but in the 1990s I listened to groups like the Minutemen, Husker Du, Minor Threat, Black Flag, and Sonic Youth because I all of my grunge rock heroes praised them and their influence. I've been revisiting that music recently, and am amazed at how vital and fresh it still sounds today.

Mudhoney was one of the first of these bands to cross my radar due their song "Overblown" on the Singles soundtrack and the fact that articles about the Seattle grunge explosion always mentioned them as godfathers of the scene. "Overblown" drew me in with its uptempo, frantic ranting, and the fact that lead singer Mark Arm was so bold as to attack the hype surrounding the Seattle scene to the point of declaring it "over and done" right at the time it was exploding. On the basis of that song alone I picked up their next album (and first for a major label), Piece of Cake. It's not a bad record, but not a particularly good one, either, and after that didn't really pay much mind to Mudhoney for awhile.

Azerrad's book piqued my curiosity about them, however, I luckily managed to find a used copy of Superfuzz/Bugmuff Plus Early Singles at my local record store. I took it home, put it on, and was immediately blown away by the first track, "Touch Me I'm Sick." It was the closest thing I'd ever heard to a Stooges song not bashed out by Iggy and the boys. Brutal, loud, and trashy while still catchy, "Touch Me I'm Sick" is a reminder of the brilliance of those 80s underground acts that lived left of the radio dial. It is entirely unfit for mainstream consumption in that the song takes the point of view of a creep, contains profanity, and features Mark Arm's yelpy scream-singing. I hear the whole thing as a kind of parody of the macho braggadocio and posturing so beloved of the hair metal frontmen who dominated MTV back in 1988 when this song came out.

I still listen to and even love contemporary independent rock music, but it has become increasingly less dangerous and less threatening. I can't stop listening to the newest War on Drugs Record, for example, but it's also something I would be totally comfortable playing around my parents. "Touch Me I'm Sick" would mortify them. Modern independent rock music has its origins in punk, and indie music's punk roots were much more apparent in the 80s than they are today, where they appear to be totally absent. It is more and more the music of hipsters with refined tastes, not the disaffected and angry. It's scarves and waxed mustaches, not flannel shirts and greasy hair. "Touch Me I'm Sick" is a good reminder that truly underground music ought to make us uncomfortable.

Friday, May 2, 2014

Real Rural America On Film

When I wrote my post a couple of weeks ago about the state of the "heartland," it inspired a conversation on Twitter about the movie Nebraska. That got me thinking about how rural life is shown in the movies, and those films that get it right. Nebraska is a film that really moved me, mostly because I had never seen the land of my birth rendered so vividly on celluloid. It captured the good, bad, and downright cringe-worthy without resorting to the usual filmic stereotypes about rural America. Most movies in a rural setting fall into one of two tropes: rural America as bucolic repository of all that is good in American life (Field of Dreams) or a backwards, violent hellhole full of bloodthirsty bigots (Deliverance). There are precious few movies that can capture the reality that lies in between. Here's my picks for the best sticks flicks:

The Last Picture Show

The book's great too, of course. This film is Peter Bogdanovich's masterpiece, and one of the few coming of age stories that's completely bereft of sentimentality. The end is perhaps the most accurate rendering I've seen of what it's like to feel trapped in a small town and unable to get out.

Nebraska

I was truly moved by this film, and not just because it made me homesick. Alexander Payne skillfully captured the desolate beauty of the Plains, and also dug deep into that world's social mores. I have been to family gatherings where men sat in the living room, silently drinking beer while watching football. I have hung out in small town bars that double as the local agora, and have seen people sit their lawn chairs in the yard to watch the cars go by. My rural Nebraska homeland is literally dying off, and Nebraska presents that painful truth well.

What's Eating Gilbert Grape?

I saw this one while still living in my hometown. There are baroque elements, like the morbidly obese mother and mentally challenged younger brother, but Gilbert's feeling of being trapped and chained down by his small town ties is a kind of quiet desperation found quite often in places like that.

Smokey and the Bandit

I know it might not seem like this one fits, since it's not social realism, but the tall tale of a hot rod driver and shipment of illegal beer. I have it on this list not only because it is a guilty pleasure of mine, but also because most of the chases are in backwoods places, and the film is full of backwoods characters who are heroic, but not in a simpering, moralistic way. The stereotypical authoritarian Southern sheriff is the foil, but he's played for laughs. It all adds up to a great time.

The Last American Hero

This forgotten gem of 1970s realism was adapted from a story by Tom Wolfe. It's about Junior Johnson, a moonshiner's son who takes his skills at outrunning the revenuers while transporting illegal hooch into the world of stock car racing. Jeff Bridges turns in a helluva performance with a character who faces a common rural dilemma: how to get to a better life without leaving behind who you are.

Breaking Away

Yet again, another film from the 1970s with a realistic view of rural life. The main character is obsessed with cycling and has become alien to his father in his quest to "break away" from his background. There is perhaps no better American film about social class dynamics in rural America, or the difficulty of striving for something beyond the rural confines without walling off one's family.

The Last Picture Show

The book's great too, of course. This film is Peter Bogdanovich's masterpiece, and one of the few coming of age stories that's completely bereft of sentimentality. The end is perhaps the most accurate rendering I've seen of what it's like to feel trapped in a small town and unable to get out.

Nebraska

I was truly moved by this film, and not just because it made me homesick. Alexander Payne skillfully captured the desolate beauty of the Plains, and also dug deep into that world's social mores. I have been to family gatherings where men sat in the living room, silently drinking beer while watching football. I have hung out in small town bars that double as the local agora, and have seen people sit their lawn chairs in the yard to watch the cars go by. My rural Nebraska homeland is literally dying off, and Nebraska presents that painful truth well.

What's Eating Gilbert Grape?

I saw this one while still living in my hometown. There are baroque elements, like the morbidly obese mother and mentally challenged younger brother, but Gilbert's feeling of being trapped and chained down by his small town ties is a kind of quiet desperation found quite often in places like that.

Smokey and the Bandit

I know it might not seem like this one fits, since it's not social realism, but the tall tale of a hot rod driver and shipment of illegal beer. I have it on this list not only because it is a guilty pleasure of mine, but also because most of the chases are in backwoods places, and the film is full of backwoods characters who are heroic, but not in a simpering, moralistic way. The stereotypical authoritarian Southern sheriff is the foil, but he's played for laughs. It all adds up to a great time.

The Last American Hero

This forgotten gem of 1970s realism was adapted from a story by Tom Wolfe. It's about Junior Johnson, a moonshiner's son who takes his skills at outrunning the revenuers while transporting illegal hooch into the world of stock car racing. Jeff Bridges turns in a helluva performance with a character who faces a common rural dilemma: how to get to a better life without leaving behind who you are.

Breaking Away

Yet again, another film from the 1970s with a realistic view of rural life. The main character is obsessed with cycling and has become alien to his father in his quest to "break away" from his background. There is perhaps no better American film about social class dynamics in rural America, or the difficulty of striving for something beyond the rural confines without walling off one's family.