When our descendants look back on our present day, they will surely judge us harshly. Here's what I imagine a textbook (or more likely e-text) on American history will say in a century.

Like the fall of the Roman empire, America's collapse took place over a long period of time, and there are conflicting interpretations as to how and why it happened. Different historians have stressed factors such as imperial overreach, the erosion of America's education system, unsustainable income inequality, and a long term decline in the production of goods. However, scholars almost totally agree that irresponsible political leaders made the nation ungovernable at a crucial point when changes could have been made to avert collapse.

Traditionally America's two political parties had hewed close to the center, but from the 1970s onward, the conservative wing of the Republican party exerted greater control, exemplified by the administrations of Ronald Reagan and George W. Bush. (See chapter 19) During the early 21st century, a group of ultra-conservative Republicans dubbed the "Tea Party," far to the right of even conservative heroes like Reagan and Bush. went from being the fringe of the GOP to its dominant force.

Unlike politicians of times past, this group refused to compromise or play by the normal rules of behavior. It took radical moves entirely unprecedented in America's history. During the presidency of Barack Obama, it commonly threatened government shut-downs and even to default on the nation's debt. This reflected the Tea Party's longer term tendency to deny the legitimacy of any Democratic president. A precursor to Congress's fight came in the late 1990s, when many future Tea Partiers had attempted to remove Bill Clinton from power over charges of sexual misconduct. Just as in the 1990s, in the early 21st century conservatives had a power propaganda network on the now obsolete media of talk radio and cable television. The "talking points" on Fox News, which acted as a mouthpiece for conservatives, had a large influence on narratives in the broader media. For that reason, as well as the corporatization of the media landscape, most Americans were told that "both sides" were extreme, and saw the Republican party as it had once been: a center right institution. Most Americans blamed the ungovernability of Washington on all politicians in general, allowing the newly radicalized Republican party to get the votes of moderates and not pay the price at the polls for their behavior.

By mid-century, however, the Tea Party would be an irrelevance, and once the Baby Boomer generation passed on, Fox News and conservative media greatly declined in popularity, much like the Hearst empire of the 20th century. Demographic and generational changes in America weakened the strength of the older rural and suburban whites who made up the Tea Party's base. Despite that fact, three decades of chaos at the high level of government had left the nation poorer, less able to pay off its debts, and unable to stop the rot that had set into an economy that was increasingly unsustainable in its inequality. While the name of the Tea Party has faded from popular consciousness, the effects of its extremism are still being felt today.

Monday, September 30, 2013

Saturday, September 28, 2013

Track of the Week: The Kinks, "Autumn Almanac"

As I have mentioned a few times before, I cherish the changes in the seasons, especially the transition from summer to autumn. When the night air gets a little chill and the leaves start to fall, I get a thrill. I've already been going back to my old seasonal rituals, including making giant pots of chili, drinking pumpkin beer, taking long walks, and watching hours of football. (Luckily having children works well with most of these activities.) Having the redhead's curse of weak skin, the summer sun is less a delight and more a painful annoyance, and so after months of suffering, I welcome days like this, when the sun shines, but a cool breeze blows.

The older I get, the more these seasonal rituals matter to me. They provide a kind continuity and security, and much comfort besides. My delight in the safety of repetition and routine is likely a sign of my descent into middle age, but with my back aching more and my metabolism slowing down rather alarmingly, I guess it's time to face facts. Ray Davies of the Kinks was an old soul himself at quite a young age, and thus the only rocker capable of penning a song like "Autumn Almanac," which is an ode to the same old simple seasonal pleasures. The character in the song opines about "football on Saturday, roast beef on Sunday" and how "this is my street, and I'm never gonna leave it, even if I live to be 99." It's one of the Kinks' jauntier tunes, clearly influenced by old music hall numbers and for that reason insanely catchy. I often find myself humming it while putting the cumin in the chili, kicking a pile of leaves, or strolling down to the Passaic River. And why not? Big things will always go wrong in our lives, it's the small things that sustain us.

Thursday, September 26, 2013

Last Week Taught Us That Some Americans' Lives Are Cheap

Remember last week? In our 24-hour news cycle world events of great import are quickly forgotten. Our nation keeps lurching forward, like a stumbling amnesiac easily distracted by bright, shiny baubles and incapable of recalling the recent past. Horrors and tragedies occur, but are quickly assigned to oblivion with all deliberate speed.

In our quest to forget we enable the same horrific crimes to be repeated. Last week brought three truly awful examples of how certain people's lives are cheap: the Navy Yard shooting, the police shooting of Jonathan Ferrell for the crime of being black, and the lonesome death of Margaret Mary Vojtko, adjunct professor.

In the aftermath of the Navy Yard shooting, where a mentally deranged man with an inexplicable access to firearms and security clearance killed twelve people, we did not even bother having a real conversation about gun control. A pile of dead first graders in Newtown didn't do the trick, so nothing will. We will continue stumbling along until the next mass killing, and afterwards the same usual suspects will spout their same usual platitudes, and nothing will get changed and more slaughters will follow.

In the case of Jonathan Ferrell, he was unarmed, yet shot dead by the police for the crime of seeking help after an accident while black. Evidently running to get assistance was some kind of threat to the officer who pulled the trigger. Funny, I don't seem to recall this ever happening to white people.

Last but not least, the plight of adjuncts briefly entered the national conversation after the death of Margaret Mary Vojtko, a longtime Duquesne University adjunct who died penniless, buried in a cardboard box. Heaven knows how many other people like her have or will soon suffer similar fates. While plenty of people in the academic world have been using her case to argue against the current adjunct system, I fear that the wider world has already stopped caring.

All of these stories affected me, not least because I know in my heart that more adjuncts will die penniless, more unarmed black men will be killed by the police, and more mass shootings will happen. What kind of society do we live in that human lives are so cheap, and that their loss barely even registers?

In our quest to forget we enable the same horrific crimes to be repeated. Last week brought three truly awful examples of how certain people's lives are cheap: the Navy Yard shooting, the police shooting of Jonathan Ferrell for the crime of being black, and the lonesome death of Margaret Mary Vojtko, adjunct professor.

In the aftermath of the Navy Yard shooting, where a mentally deranged man with an inexplicable access to firearms and security clearance killed twelve people, we did not even bother having a real conversation about gun control. A pile of dead first graders in Newtown didn't do the trick, so nothing will. We will continue stumbling along until the next mass killing, and afterwards the same usual suspects will spout their same usual platitudes, and nothing will get changed and more slaughters will follow.

In the case of Jonathan Ferrell, he was unarmed, yet shot dead by the police for the crime of seeking help after an accident while black. Evidently running to get assistance was some kind of threat to the officer who pulled the trigger. Funny, I don't seem to recall this ever happening to white people.

Last but not least, the plight of adjuncts briefly entered the national conversation after the death of Margaret Mary Vojtko, a longtime Duquesne University adjunct who died penniless, buried in a cardboard box. Heaven knows how many other people like her have or will soon suffer similar fates. While plenty of people in the academic world have been using her case to argue against the current adjunct system, I fear that the wider world has already stopped caring.

All of these stories affected me, not least because I know in my heart that more adjuncts will die penniless, more unarmed black men will be killed by the police, and more mass shootings will happen. What kind of society do we live in that human lives are so cheap, and that their loss barely even registers?

Tuesday, September 24, 2013

The Academic Misery Index Quiz

A couple of years ago, when this blog had yet to find much of an audience beyond my friends, I put together something I called the Academic Misery Index Quiz. It was a light-hearted way to present the question of whether one should stay in their academic position or try to get out of it, and I had a lot of fun putting it together. Two years on, I know a lot more people who are doing the mental math and trying to figure out whether they ought to stick with the profession or not. If possible, the level of academic misery has actually risen rapidly in the last two years, which makes me think an updated version of the quiz is necessary. If you take the quiz, let me know what tweaks are still necessary.

Part One

Each "A"answer is worth zero points, each "B" answer one point, each "C" answer two points, and each "D" answer five points.

1. How would you describe your university?

A. A nationally recognized institution with a stellar reputation.

B. A solid school that's not quite the big time, but with plenty of name recognition.

C. A "first rate second rate" college/university with plenty of faults but a basic commitment to upholding the standards of the profession.

D. A dysfunctional, bottom-feeding fly-by-night operation so obscure that when you go to conferences and tell people where you're from, they give you a blank stare or judgemental glare.

2. How would you describe the students at your university?

A. They are self-motivated, mature adults with a love of learning.

B. They are smart yet entitled children of privilege who need some prodding.

C. They are middle of the road intellectually and see their classes with a mostly vocational understanding, i.e., "why do I have to take this class?"

D. They are barely literate and seem to have no clue whatsoever as to why they are in college in the first place. The few brain cells they have left after nightly games of beer pong are devoted to texting.

3. How would you describe the town where your university is located?

A. A world-class city brimming over with fine dining, cultural events, and like-minded individuals.

B. An idyllic college town with a relaxed atmosphere and lots of cultural amenities/good but not great city with plenty to do.

C. A non-college town, mid-sized city that's a little boring, but at least has all the stuff you need, and the occasional cultural event.

D. A backwoods 'burg lacking a decent sit-down restaurant where the locals actively resent the university community for making them look like the countrified rubes that they are.

4. What are the politics of your department like?

A. What politics? We all love each other and most of us are good friends.

B. There are minor disputes, and we aren't all that close, but mostly because we're too busy to fight.

C. The silverbacks and the young'uns clash from time to time, but mostly inside departmental and committee meetings. We all know the two people who hate each other's guts, but the rest of us stay out of that mess.

D. They make Renaissance Florence look like an eight year old girl's tea party. Long-held grudges, character assassination, and intentional sabotage are the norm.

5. How would you describe your chair?

A. A far-sighted leader who listens well and tirelessly strives to protect the best interests of the department.

B. A competent technocrat who gets the job done but lacks vision. No real complaints.

C. A well-meaning buffoon who mostly tries to avoid doing work.

D. A malicious control-freak who plays favorites and considers any alternative viewpoint to be treason.

6. What is your institution doing with assessment?

A. What's assessment?

B. Writing the standard boilerplate to keep the accreditation people happy but little that faculty have to deal with.

C. There's lots of pointless meetings and discussion and it's a big annoyance, but profs are not really told what to do in the classroom, and feel free to ignore the assessment regime's dictates.

D. Faculty have lost control over what material is taught in their courses and spend a great deal of their time filling out asinine forms and getting reprimanded for failing to follow hopelessly labrynthine policies to the letter.

7. What happens when you report a plagiarism case?

A. I have to hold back the chair and dean from nailing the student to a cross.

B. There's lots of paperwork and I am asked to give the student the benefit of the doubt, but if I want to punish a student, I am able to do it.

C. I am reluctant to push cases because I am usually asked to lessen my penalties.

D. The chair and other higher-ups immediately take the student's side, and get irritated with me for taking up their time.

8. How would you describe your university's priorities?

A. To achieve educational excellence and foster world-class scholarship.

B. To provide a quality education for its students and give some support to research.

C. Mostly football and manipulating the categories in the US News rankings.

D. To keep distracting outsiders from the fact that the place is a complete joke and ought to be shut down.

9. What's the financial outlook of your institution like?

A. We are a wealthy private school with a huge endowment that our regents swim in like Scrooge McDuck.

B. We have had to make some cutbacks in course offerings and travel budgets, but faculty have mostly been spared.

C. Our state government is run by anti-intellectual GOP blockheads who force us to make do with less with each passing year OR (if a private school) our endowment is weak but the school is above water. There's less money for research and few raises, but our jobs are relatively safe.

D. We have a psychotic governor hell-bent on destroying whole programs and firing tenured professors with budget cuts/we are a poor private school running on a showstring budget always begging alumni for money which is only barely keeping us afloat for just one more year.

10. When you talk to your faculty friends outside of class, what sentence are you most likely to utter or hear?

A. "Wasn't the pinot grigio at the faculty reception last night delightful?"

B. "With the cutbacks it looks like I won't be able to get the library to order all of the books on my list."

C. "I don't know how they expect me to teach more students with these increased tenure and service requirements."

D. "If I can't get a job somewhere else this year I will end up dying of alcohol poisoning."

11. How would you describe a typical departmental faculty meeting?

A. A welcome opportunity to get everyone together and be collegial.

B. A minor annoyance that is usually blessedly brief.

C. A prolonged, unorganized exercise in silverback resentment and junior scholar superkeenerism that rarely solves anything.

D. A horrifying parade of stupidity and malice so nerve-wracking that I have to take a xanax to be able to endure it without crying or running out screaming.

12. What is your school's attitude towards office hours?

A. We are supposed to hold them at some point, but I'm not sure when they are, exactly.

B. We have three mandated office hours, but it isn't much of a burden.

C. We have five office hours a week and are expected to keep our doors open at all times during them.

D. We have ten office hours a week, and the chair will call me at home if I happen to duck out five minutes early on a slow day.

13. How does your department handle academic advising?

A. Not sure, but I think we have peons for that.

B. A couple of poor saps do it as part of their service, but get a course reduction.

C. We all have to pitch in and do it, but at least we share the burden.

D. I am one of the people press-ganged into doing it without a course reduction, and typically have two weeks of my semester rendered unproductive by a constant stream of slackjawed idiots who want me to figure out their schedules for them.

14. How would you describe your dean?

A. A wonderfully engaging ally who is always willing to listen.

B. A careerist looking to climb the ladder to another school, but at least competent.

C. A meddling dolt who spends meetings mouthing every trendy administrative catchphrase, from "accountability" to "sustainability."

D. A ruthlessly authoritarian presence constantly forcing departments to conform to their vision of the university.

15. Which type of conversation among faculty are you most likely to hear as you pass down the hallway?

A. A witty and engaged discussion of the finer points of research and/or pedagogy.

B. The usual small talk.

C. Lots of complaining about the latest administrative initiative.

D. Resentful white men decrying their own supposed marginalization with plenty of borderline racist, sexist, and homophobic comments thrown in.

Part Two

These questions have more points at stake because they make the difference between a tolerable situation and soul-crushing anomie. Each "A" answer is worth 0 points, each "B" answer is worth five points, each "C" answer ten points and each "D" answer fifteen points.

1. Which best describes the kind of academic job that you currently have?

A. You possess the great golden ring of tenure.

B. A tenure track position with the tenure clock ticking away.

C. A "visitor" or lecturer position with limited appointment and substandard pay.

D. A temporary adjunct position with no security paid by the course.

2. How far away does your job force you to live from your significant other?

A. You get to live with your significant other.

B. You have to live in different towns, but are able to see each other on the weekend.

C. You live so far apart that you cannot see each other more than once a month.

D. You used to have a significant other until your forced separation destroyed your relationship/you are forced to live in such a benighted rural outpost that Ron Paul has a better chance of getting elected president than you do of finding a suitable partner.

3. When you show up at work on Monday morning, what statement best describes your thought process?

A. It's great to be back to doing the thing that I love.

B. This week will be good if I don't have any more bullshit excuses from my students and just plain bullshit from my administrators.

C. I'd like this job a lot more if I was on the tenure track.

D. How can I get to my office without crossing paths with the colleagues who make me want to stab myself with a dull butter knife?

Scoring:

After tallying up your scores, look the misery index below:

0-15 points: Shangri-La

Congratulations, you are living the academic dream! The next time you think about complaining about your job, please remember that you've got some serious First World Problems.

16-30 points: The Good Life

You have the right to the occasional gripe, but things are looking good. If you can avoid the tendency in this profession never to be satisfied, you'll have a happy and fulfilling time at your institution.

31-50 points: The Danger Zone

If you don't absolutely love academic work with all of your heart and soul, it might be time to explore other options.

50+ points: Soul-sucking Misery

Get the hell out while you are still young and relatively sane. If not you will end up like the senior colleagues you respect who always have looks of bemused sadness on their faces.

Monday, September 23, 2013

Track of the Week: The Monkees, "Pleasant Valley Sunday"

I picked up the most recent issue of Weird N.J. yesterday, and was interested to find out that songwriters Carole King and Gerry Goffin had lived for a time in suburban West Orange, New Jersey. I was even more intrigued by the fact that "Pleasant Valley Sunday," one of the hits they penned for the Monkees, was inspired by West Orange, and Pleasant Valley Way in particular. This fact hit home, since my wife and I are in the process of looking for homes, and it is likely that we will soon be leaving Newark's urban grit for the leafier environs of suburban Essex County.

It's a move that I am deeply ambivalent about, and my feelings can be neatly summed up by listening to "Pleasant Valley Sunday." The song details a lazy weekend day in suburbia marked by consumerism, boredom, and complacency. The narrator concludes, "I need a change of scenery," which is evidently what Gerry Goffin thought at the time about West Orange. I am a little ashamed to admit this, but I was into the Monkees before I liked the Beatles, and this song was one of the first social commentary songs that I "got." Even as an eleven-year old, I understood the message loud and clear.

As I aged into my teen years, I began to eagerly await the day I would leave my rural hometown and live a more bohemian lifestyle. I read the Beats and Hunter S. Thompson, and even though I didn't drink or smoke weed or rebel in any real outward way, I saw myself living an unconventional life where I would be as likely to become a suburban homeowner as I would to become the king of France. Currently I live in a densely populated immigrant neighborhood in a city that has become a byword for blight where the local white suburbanites fear to tread, so I guess I accomplished my mission.

It's not sustainable, though. My wife used to live in our apartment by herself, now we've got the two of us, two children, a dog and a cat. It's simply way too cramped to stay here, and buying in this neighborhood is surprisingly pricey. I'd love to move to New York City, but the state law mandating that New Jersey teachers must live in state is an impediment, as well as the fact that NYC is becoming a playground for the wealthy where it is simply too expensive for two teachers to have a middle class family and live a tolerable life. So we look west to the suburbs, where I hope to at least find a tribe of like-minded people there who don't buy into the values of "status symbol land"so that I won't be left looking for a "change of scenery."

Saturday, September 21, 2013

How to Travel in Nebraska

Last month I visited my Nebraska homeland, which apart from my alarm at the political climate there, was a great, relaxing time. Apart from seeing my family, it was great to be underneath the wide plains sky and gaze out upon the beautiful prairies. We also took some cool trips into the country, and spent some time in Omaha, a seriously up-and-coming city with lots to offer. I mention this because over the years, when I tell people I am from Nebraska, they often respond by calling it flat, boring, and desolate. I soon discover that the only experience they have to back up this perception came from a one-time car trip across the state on Interstate 80. This means that the supposed coastal sophisticates who register this opinion are actually incredibly ignorant. (I wouldn't blame them, if not for the arrogance with which they run down a place they never really saw or understood.)

Instead of getting mad at such slights, I thought, as a public service, I would offer a guide on how to travel in Nebraska. This is meant both for those passing through, as well as those looking to stop. One nice thing about the places I will mention is that they are bereft of out of state tourists, meaning that a visitor will find them to be inexpensive, uncrowded, and patronized by friendly locals. Below are some tips and rules for having a great travel experience in Nebraska

The Flat is Not Universal

Yes, many parts of Nebraska are very flat. However, most of the state is not. The perception problem stems from the fact that Interstate 80, the only one in the state, mostly follows the Platte River valley, by far the state's flattest section (and where I happened to grow up.) Nuckolls County, where my dad hails from, is so hilly that a family legend says that my great-great-grandmother from the swampy flatlands of northern Germany died in despair once her immigrant daughter's family paid for her passage over the Atlantic. On the wagon trip from the train station to the farm she supposedly whimpered "not another hill!" and died soon afterward. The northwestern third of Nebraska is covered by the aptly named Sandhills, and Omaha is built on steep bluffs with streets as treacherous as those in San Francisco. Go there and tell me Nebraska is uniformly flat.

Get Off the Interstate

If you want to get away from the flat, get off the interstate. Not only will you get some more varied terrain, you will also get to experience some beautiful countryside. Most state highways don't have shoulders, meaning that the prairie comes right up to the road. For those, like me, who enjoy the driving as much as getting to the destination, these roads are a pure pleasure. The absolute best is state Highway 2, which cuts diagonally across the breathtakingly empty Sand Hills. A close second is Highway 83, which also goes across the Sand Hills and ends up at the scenic Niobrara River.

Lincoln and Omaha are Ideal Overnight Stops

If you're planning on just gunning it down Interstate 80 through Nebraska, you should at least plan to stop overnight for a rest in either Lincoln or Omaha. Although Nebraskans like to think of themselves as rural folk, an increasingly higher percentage of them live in these two growing, thriving cities. Both have a wealth of great bars and restaurants with low prices. Downtown Lincoln is a great place to hang out, and the Old Market in Omaha is one of my favorite places in the world to spend a lazy evening. These two locations also have well-stocked and affordable used book stores and quality microbreweries to boot. Between Chicago and Denver there really aren't any other cities as interesting and full of things to do.

Eat at Small Town Bars

If you want to find a good place to eat on the road in rural Nebraska, sites like Yelp will be of no help to you. Outside of Lincoln and Omaha, the only places to eat are either national chain restaurants or places so local that only locals know about them. These are also not the most tech-savvy locals, so the places they love won't get online raves. The bar and grill is the lifeblood of most small towns in Nebraska. People might go there to drink at night, but during the day they are where folks get together to talk, drink coffee, and have lunch. Each town has one, and many of them serve amazing food at low prices with good service and plenty of character to boot. As a public service, here are a few worth seeking out, some of which are located near major highways:

Whiskey River in Dannebrog: Went there on my last trip and had a killer prime rib sandwich for eight bucks.

The Opera House in Fairfield: Have not been there yet, but my cousins say there's good food and several local beers on tap.

Ole's in Paxton: A little creepy because it is full of taxidermy from all over the world, but totally kitsch-tastic for that reason

Dick's in Lawrence: My father's hometown bar, and the rock of that community.

Tubb's Pub in Sumner: The best chicken fried steak and hot beef sandwiches I've ever had. Well worth the detour from I-80.

A Short List of Great Places to See

As with the food, the best places to see in Nebraska are off of the beaten path, and well-known to locals, but unknown to outsiders. Here are some of my favorites:

Red Cloud: This is the hometown of Willa Cather, the greatest author the Cornhusker State ever produced. In addition to some interesting sites for Cather-holics, south of town there is a preserved grassland which has restored the prairie to how it looked 150 years ago. Its vastness is truly a sight to behold.

Valentine: Visit here if you want to canoe or innertube down the beautiful Niobrara River. Conditions are ideal, the landscape gorgeous, and the prices much lower than on more famous rivers.

Highway 2: The Sand Hills are one of the most desolately beatific landscapes I've ever seen, and Nebraska Highway 2 cuts diagonally right across them. Every time I go home I try to drive at least a short stretch of Highway 2, and it always has a soothing effect on my soul.

Carhenge: Outside of the Sand Hills town of Alliance, a local man built a replica of Stonehenge using junked cars. It has a strange genius to it, and I think works as a profound commentary on consumption.

Scottsbluff: Also in the Panhandle, climbing this giant rock provides awesome vistas.

Ft. Robinson: Crazy Horse met his end at this old army base in the northwest corner of the state. Very interesting spot for history buffs.

Toadstool State Park: Getting here requires going down some seriously dusty gravel roads to a place that seems like another planet. Out there in the middle of nothing lies a large outcropping of rock, which erosion has formed into crazy shapes that look like toadstools. It is hard to describe just how isolated this place is, or how it gives the visitor such a brush with the uncanny. It's like Devil's Tower in that respect, but without others around to spoil the effect.

Instead of getting mad at such slights, I thought, as a public service, I would offer a guide on how to travel in Nebraska. This is meant both for those passing through, as well as those looking to stop. One nice thing about the places I will mention is that they are bereft of out of state tourists, meaning that a visitor will find them to be inexpensive, uncrowded, and patronized by friendly locals. Below are some tips and rules for having a great travel experience in Nebraska

The Flat is Not Universal

Yes, many parts of Nebraska are very flat. However, most of the state is not. The perception problem stems from the fact that Interstate 80, the only one in the state, mostly follows the Platte River valley, by far the state's flattest section (and where I happened to grow up.) Nuckolls County, where my dad hails from, is so hilly that a family legend says that my great-great-grandmother from the swampy flatlands of northern Germany died in despair once her immigrant daughter's family paid for her passage over the Atlantic. On the wagon trip from the train station to the farm she supposedly whimpered "not another hill!" and died soon afterward. The northwestern third of Nebraska is covered by the aptly named Sandhills, and Omaha is built on steep bluffs with streets as treacherous as those in San Francisco. Go there and tell me Nebraska is uniformly flat.

Get Off the Interstate

If you want to get away from the flat, get off the interstate. Not only will you get some more varied terrain, you will also get to experience some beautiful countryside. Most state highways don't have shoulders, meaning that the prairie comes right up to the road. For those, like me, who enjoy the driving as much as getting to the destination, these roads are a pure pleasure. The absolute best is state Highway 2, which cuts diagonally across the breathtakingly empty Sand Hills. A close second is Highway 83, which also goes across the Sand Hills and ends up at the scenic Niobrara River.

Lincoln and Omaha are Ideal Overnight Stops

If you're planning on just gunning it down Interstate 80 through Nebraska, you should at least plan to stop overnight for a rest in either Lincoln or Omaha. Although Nebraskans like to think of themselves as rural folk, an increasingly higher percentage of them live in these two growing, thriving cities. Both have a wealth of great bars and restaurants with low prices. Downtown Lincoln is a great place to hang out, and the Old Market in Omaha is one of my favorite places in the world to spend a lazy evening. These two locations also have well-stocked and affordable used book stores and quality microbreweries to boot. Between Chicago and Denver there really aren't any other cities as interesting and full of things to do.

Eat at Small Town Bars

If you want to find a good place to eat on the road in rural Nebraska, sites like Yelp will be of no help to you. Outside of Lincoln and Omaha, the only places to eat are either national chain restaurants or places so local that only locals know about them. These are also not the most tech-savvy locals, so the places they love won't get online raves. The bar and grill is the lifeblood of most small towns in Nebraska. People might go there to drink at night, but during the day they are where folks get together to talk, drink coffee, and have lunch. Each town has one, and many of them serve amazing food at low prices with good service and plenty of character to boot. As a public service, here are a few worth seeking out, some of which are located near major highways:

Whiskey River in Dannebrog: Went there on my last trip and had a killer prime rib sandwich for eight bucks.

The Opera House in Fairfield: Have not been there yet, but my cousins say there's good food and several local beers on tap.

Ole's in Paxton: A little creepy because it is full of taxidermy from all over the world, but totally kitsch-tastic for that reason

Dick's in Lawrence: My father's hometown bar, and the rock of that community.

Tubb's Pub in Sumner: The best chicken fried steak and hot beef sandwiches I've ever had. Well worth the detour from I-80.

A Short List of Great Places to See

As with the food, the best places to see in Nebraska are off of the beaten path, and well-known to locals, but unknown to outsiders. Here are some of my favorites:

Red Cloud: This is the hometown of Willa Cather, the greatest author the Cornhusker State ever produced. In addition to some interesting sites for Cather-holics, south of town there is a preserved grassland which has restored the prairie to how it looked 150 years ago. Its vastness is truly a sight to behold.

Valentine: Visit here if you want to canoe or innertube down the beautiful Niobrara River. Conditions are ideal, the landscape gorgeous, and the prices much lower than on more famous rivers.

Highway 2: The Sand Hills are one of the most desolately beatific landscapes I've ever seen, and Nebraska Highway 2 cuts diagonally right across them. Every time I go home I try to drive at least a short stretch of Highway 2, and it always has a soothing effect on my soul.

Carhenge: Outside of the Sand Hills town of Alliance, a local man built a replica of Stonehenge using junked cars. It has a strange genius to it, and I think works as a profound commentary on consumption.

Scottsbluff: Also in the Panhandle, climbing this giant rock provides awesome vistas.

Ft. Robinson: Crazy Horse met his end at this old army base in the northwest corner of the state. Very interesting spot for history buffs.

Toadstool State Park: Getting here requires going down some seriously dusty gravel roads to a place that seems like another planet. Out there in the middle of nothing lies a large outcropping of rock, which erosion has formed into crazy shapes that look like toadstools. It is hard to describe just how isolated this place is, or how it gives the visitor such a brush with the uncanny. It's like Devil's Tower in that respect, but without others around to spoil the effect.

Thursday, September 19, 2013

How To Tell If You're a Declasse Academic

I realize this post might be arcane to those who have never worked in the academic field, but bear with me here, since I think it touches on some general social class issues in this country.

One interesting thing I've noticed about academics is that while almost all of them drive sensible cars, live in modest homes, and buy their clothing off the rack (at least in the humanities), there are still some subtle and very powerful class markers at play. I've had many conversations over the years with friends sharing stories about how oblivious our advisors and committee members could be to our economic situations, and got talking about how some academics are "to the manner born": they grew up in academic families, or at least among the well-educated upper bourgeoisie in places that hold cultural cachet. (i.e., not Nebraska) Having an academic job requires navigating its culture, which is awfully tough. These days, with the jobs drying up, the cultural knowledge and connections that come from a bourgeois background are more important than ever.

While they don't make a lot of money relative to others with advanced education, members of the academic profession still attach a lot of importance to the accoutrements of the high class life. This often made academic culture hard for me to navigate at times; I grew up in the rural petite bourgeoisie, i.e. eating casseroles instead of cavier. I never really thought I was a member of the club, that I didn't mesh with its culture or priorities. I guess I was right all along, and I wonder how many people who have been squeezed out of the profession in recent years felt the same way. Without further ado, here are some questions that can help you find out which camp you belong in.

You might be a declasse academic if:

You or any of your family members has ever had a job where you "washed up" after coming home from work.

(Thanks to Brian I. for this one. I'm amazed at the number of people in my profession who've never had to get their hands dirty outside of gardening.)

You actually worked jobs during the summer in grad school to support yourself.

(I can't believe the number of profs who expect their students to magically conjure money to support themselves while researching in the summer.)

Before you went to grad school the only categories you knew for wine were "red" or "white."

You have never used the word "summer" as a verb (as in "we summered in the Hamptons this year").

Members of your family were drafted during Vietnam and couldn't get out of it. (Like a lot of other guys, my relatives didn't want to go, but they didn't have a choice.)

Getting a Ph.D. makes you the most educated member of your family.

Growing up you took family vacations by car (not plane) to locations in the US (not Europe or elsewhere if you took vacations at all.)

You or your family members wear or have worn "trucker caps," overalls, or cowboy boots not as ironic fashion statements but for purely practical reasons.

Your family pressured you NOT to go to the Ivy League for college, because why would you want to be around those snobby rich assholes who think their shit don't stink? (That's the message I got from my parents, at least.)

People in your social circle growing up viewed New York City as a sink of iniquity, not the shining center of the universe.

Your idea of a good restaurant is a place that has "good food and a lot of it for a reasonable price."

You drank Pabst Blue Ribbon before it became a hipster beer. (I have to admit, I totally jumped on the hipster bandwagon with this one.)

You don't utter asinine phrases like "I don't think I know any Republicans." (I actually heard this said before the 2004 election and wanted to put my head through the wall. No wonder the Left got thumped for so long! So many on our side saw conservatives in zoological terms.)

You live in a Midwestern college town like Champaign-Urbana and you don't constantly complain about how it isn't New York or San Francisco. In fact, you really like it.

You don't drop your alma mater's name into conversations, or automatically expect other people to know about it.

When you go home for the holidays you feel more and more estranged from the values of your upbringing with each passing year, and your family doesn't seem to understand who you've become.

You've never had a conversation comparing the relative merits of private boarding schools in the northeast. (I was around some people doing this on the first day of my master's degree program, that's when I began to realize that I was entering into a different world.)

That's all I can think of for now, and of course not all apply to everyone. Feel free to add your own.

[AUTHOR'S CAVEAT: I should note that the examples I provide are based mostly on my own experience as a lower-middle class white man from the rural Midwest, so they're not meant to be exhaustive or definitive. Other people with different backgrounds from me will certainly have different class markers to contribute to the conversation.]

Tuesday, September 17, 2013

Double Live!

Arena rock shows today are kinda lame: expensive, impersonal, and lacking the chaos and clouds of ganja smoke necessary to create the right atmosphere. I secretly long to start a cover band called Double Live that would only play songs by 70s bands that recorded double live albums. We could bring some of that old magic back, but to the club stage. Who's with me?

Here are some of the songs we'd do (played like they are on the double live records, not in the studio):

Humble Pie, "I Don't Need No Doctor"

Sadly someone has pulled the video of this from YouTube. It's the closing track on Humble Pie's killer double live album Performance: Rockin' the Fillmore. They were a well-regarded and well-attended live act, despite their lack of hit records. One listen to "Stone Cold Fever" from that album will clue you in.

This track is the Mona Lisa, the Sistine Madonna, the Venus de Milo of double live songs. It not only anchored the biggest double live album of all time, it has a talking guitar, rocknroll decadence-drenched lyrics, and more overindulgence than Liberace's wardrobe.

Because the setlist would not be complete without some Grand Funk. It'd be like making a martini without the gin.

'Cuz a double live frontman's gotta have something to strut to.

I am cheating a little because Foghat put a live record, but it wasn't double live. I consider it to be some kind of crazy oversight, since if there is one band that embodies the empty-headed good time hard riff rocking spirit of double live as a genre, it's Foghat for sure.

Before REO hit power-ballad paydirt in the early 1980s, they toured for years as a hard-rockin' but little regarded band. Their double live record, Live: You Get What You Play For, is the apotheosis of their dues paying years, a sign that they are soon to break out at long last. (You Can Tune a Piano But You Can't Tuna Fish was their first hit album, and it came out a year later.) For this one we'd need a siren to kick it off, and it would have to be the last song of the main set, so the singer (perhaps me) can intone "last song, people!"

Kiss sucks, if you ask me, and Gene Simmons is an insufferable prick. However, the band managed to put together one truly glorious slab of rock and roll awesomeness in its career, a song that fits the double live ethos to a t. This song would definitely come on the encore.

Monday, September 16, 2013

Track of the Week: The Who, "Sparks (Live)"

Tommy was the first Who album I ever owned, at it was a terrible disappointment. I was attracted to it through the concept -which appealed to a teenage outcast- and hearing the propulsive, explosive "Pinball Wizard" on classic rock radio. I found, and still find, the album to be constipated and uneven. Apart from the aforementioned "Pinball Wizard" and "We're Not Gonna Take It," the second half is mostly uninteresting plot exposition. The problem with concept albums is that they force songs to be contorted into a framework that doesn't really suit them, or they spawn crummy songs there to move plot. The Who Sell Out is a far superior album because the concept comes out of the fake commercials and radio promos between songs, which are fantastic and not linked by any common theme or story.

While Tommy doesn't hold up well as a studio album, I continue to be blown away by the live version included on the recent two-disc expanded version of Live at Leeds. Many weak songs have been excised, the band has perfected their approach after performing it for two years, and they really know how to cut loose. To hear this, look no further than the instrumental "Sparks," which goes from being loud in a mannered fashion on record to an absolute explosion of sound onstage. The build up to the climax is exhilarating, and the moment at three minutes in when the dam finally bursts is one the most thrilling things I've ever heard. When I am trying to get psyched up for the beginning of the work week on a Monday morning, I crank this one up through my headphones while riding the subway, and it never fails to get my heart pounding and my head in the right place.

Saturday, September 14, 2013

Why Adjunctification Does Not Improve Learning

There's a recent study of professors at Northwestern University that purports to show that students of adjuncts there learn better than those of tenured faculty in introductory-level classes. Jordan Weissmann at The Atlantic has extrapolated from this inconclusive study of one non-representative institution that adjuncts definitively make better teachers because they devote all their time to teaching, rather than research. The implication he highlights, of course, is that adjunctification is all hunky-dory because it means better classroom instruction. Others like Pan Kisses Kafka and William Pannapacker have already given this "pipsqueak" his due, but I can't let this go without offering my much less respected opinion.

As someone who has taught as a TA and both on and off the tenure-track, I've seen that reality is a lot different than this. In the first place, Weissmann bases his thoughts on the totally erroneous assumption that adjuncts and other contingent faculty aren't focused on research. When I was a visiting assistant professor I spent two years busting my hump to get articles out in order to get a tenure-track job. Perhaps more time consuming, I had to put together over thirty job applications a year, which was like its own part time job in itself. During my second semester, I made the conscious decision to put my teaching on the back burner because if I didn't, I would not have been able to write the conference papers and publications necessary to get a better job. My teaching suffered, but I had built up enough goodwill from my first semester that I knew I wouldn't lose my job, and the following summer I got an article accepted into a top journal that helped propel me on the job market to a tenure-track position. A second article followed in the early fall, and I was able to put more emphasis on my teaching. I felt horrible for short-changing my students that one semester, but it had to be done, and was a conscious choice that many adjuncts and "visitors" must make.

Despite those pressures, I've known many contingent faculty who were fantastic teachers. Some of them were high school teachers who had retired or who were moonlighting, and so had a tremendous amount of classroom experience. With the contraction of the tenure track job market, there were also a lot of folks who had the bona fides to be on the tenure track, but who had been done wrong by the system. (I fancied myself one of these types.) I published more in my two years as a visitor than many fullprofs in my department had done through their entire careers (giving lie to Weissmann's thesis, which only holds for research universities.) I have multiple friends who have published well-received books with good presses while working as contingent faculty, and who also happen to be fine teachers. Their abilities have nothing to do with having more time for teaching, and everything to do with the fact that they are talented people who ought to have better jobs.

Despite the number of great teachers off the tenure track, many of whom are simply better at their jobs than those with tenure, there are plenty who struggle. Much of this has to do with the privations and stress of contingent work. Many adjuncts must cobble together classes at multiple institutions, leaving them stretched thin and worn out from their commutes. Others have to work side jobs to make ends meet, like a friend of mine who worked for a wine wholesaler while adjuncting four classes. Like me, he had needed to do emergency dental work, and adjuncts and visitors alike at my institution did not have dental insurance. The expense meant that he had to take additional work, and I had a great deal of added stress over finding a dentist I could afford who could help me.

By and large, adjuncts get little to no institutional support. Many don't even have a desk or office space, or must use spaces that are humiliatingly shitty. There is almost no mentorship for young contingent teachers, and often no oversight, either. Along with the great contingent teachers I've known, I've seen others who were horribly irresponsible. One I knew had carried on sexual relations with a former student (while she was still enrolled in the university) and once left for a week to attend a wedding, and had one of his students show films. Another was totally unqualified to teach world history, and so merely read aloud from the textbook. His evaluations were horrible (for the right reasons, this time) but he kept his job because the institution needed a warm body in the classroom. My friends who busted their butts got so demoralized, since we were all paid the same amount of money, and all given the same amount of recognition: zilch. It quickly became obvious that the only thing keeping me responsible in the classroom was my own conscience. That is hardly a recipe for quality education, and certainly breeds feelings of cynicism and even despair among contingent faculty.

Adjunct labor is a system that is rotten to the core, and it's only getting worse. Like all other wealthy industries, higher education wants workers who are powerless, replaceable, and above all, cheap. That is the only real reason for the rise of contingent labor in the academy, and to imply that this is possibly a good thing and good for learning is sophistry, cant, and utter bullshit of the worst variety.

As someone who has taught as a TA and both on and off the tenure-track, I've seen that reality is a lot different than this. In the first place, Weissmann bases his thoughts on the totally erroneous assumption that adjuncts and other contingent faculty aren't focused on research. When I was a visiting assistant professor I spent two years busting my hump to get articles out in order to get a tenure-track job. Perhaps more time consuming, I had to put together over thirty job applications a year, which was like its own part time job in itself. During my second semester, I made the conscious decision to put my teaching on the back burner because if I didn't, I would not have been able to write the conference papers and publications necessary to get a better job. My teaching suffered, but I had built up enough goodwill from my first semester that I knew I wouldn't lose my job, and the following summer I got an article accepted into a top journal that helped propel me on the job market to a tenure-track position. A second article followed in the early fall, and I was able to put more emphasis on my teaching. I felt horrible for short-changing my students that one semester, but it had to be done, and was a conscious choice that many adjuncts and "visitors" must make.

Despite those pressures, I've known many contingent faculty who were fantastic teachers. Some of them were high school teachers who had retired or who were moonlighting, and so had a tremendous amount of classroom experience. With the contraction of the tenure track job market, there were also a lot of folks who had the bona fides to be on the tenure track, but who had been done wrong by the system. (I fancied myself one of these types.) I published more in my two years as a visitor than many fullprofs in my department had done through their entire careers (giving lie to Weissmann's thesis, which only holds for research universities.) I have multiple friends who have published well-received books with good presses while working as contingent faculty, and who also happen to be fine teachers. Their abilities have nothing to do with having more time for teaching, and everything to do with the fact that they are talented people who ought to have better jobs.

Despite the number of great teachers off the tenure track, many of whom are simply better at their jobs than those with tenure, there are plenty who struggle. Much of this has to do with the privations and stress of contingent work. Many adjuncts must cobble together classes at multiple institutions, leaving them stretched thin and worn out from their commutes. Others have to work side jobs to make ends meet, like a friend of mine who worked for a wine wholesaler while adjuncting four classes. Like me, he had needed to do emergency dental work, and adjuncts and visitors alike at my institution did not have dental insurance. The expense meant that he had to take additional work, and I had a great deal of added stress over finding a dentist I could afford who could help me.

By and large, adjuncts get little to no institutional support. Many don't even have a desk or office space, or must use spaces that are humiliatingly shitty. There is almost no mentorship for young contingent teachers, and often no oversight, either. Along with the great contingent teachers I've known, I've seen others who were horribly irresponsible. One I knew had carried on sexual relations with a former student (while she was still enrolled in the university) and once left for a week to attend a wedding, and had one of his students show films. Another was totally unqualified to teach world history, and so merely read aloud from the textbook. His evaluations were horrible (for the right reasons, this time) but he kept his job because the institution needed a warm body in the classroom. My friends who busted their butts got so demoralized, since we were all paid the same amount of money, and all given the same amount of recognition: zilch. It quickly became obvious that the only thing keeping me responsible in the classroom was my own conscience. That is hardly a recipe for quality education, and certainly breeds feelings of cynicism and even despair among contingent faculty.

Adjunct labor is a system that is rotten to the core, and it's only getting worse. Like all other wealthy industries, higher education wants workers who are powerless, replaceable, and above all, cheap. That is the only real reason for the rise of contingent labor in the academy, and to imply that this is possibly a good thing and good for learning is sophistry, cant, and utter bullshit of the worst variety.

Thursday, September 12, 2013

A Happy Zeptember to You All

I'd probably heard the phrase Zeptember on a classic rock radio station some time, but I will always associate it with my two years living in Grand Rapids, Michigan. A friend of mine there and I would get together on September evenings and play Zeppelin while enjoying the last outdoor beer and grilled foods before winter's cold set in. In a place like western Michigan, where winter lasts for over five wretched months without sunlight and comes with almost daily dumpings of lake effect snow, the last warm evenings of September take on an almost unbearably elegiac quality. Zeppelin's witchy, mystical side makes for great listening when the seasons change, so I have carried on the Zeptember tradition even though I live far from the Wolverine State.

Of all the songs in their catalog, I associate "In the Light" from Physical Graffiti the most with Zepptember. The simple reason is that I bought it on CD after years of dallying during my first September in Michigan, and the old copy I purchased from a hole-in-the-wall used record store had disc 2 where disc 1 should have been. I put it on, expecting to hear the heavy, skanky riff of "Custard Pie," but was instead hit with a synthesizer imitating the eerie moans of an Irish horn. I instantly fell in love with the haunting sound and spent a couple of weeks playing it right when I got out of bed in the morning. To this day I associate this song with my earliest days as a visiting assistant professor, working eighty hours a week with music one of the few pleasures to afford myself.

There are other Zeppelin songs, many not necessarily well known, that I reserve for Zeptember, and others more famous I eschew, like "Whole Lotta Love," which speak more to spring's change of season and attendant libidinous awakening. Despite its subject matter, I think the classic b-side "Hey Hey What Can I Do" has an autumnal vibe. Perhaps its just the acoustic guitars, which sound like falling leaves in my head. Speaking of falling leaves, when all begins to wither and die around me, "In My Time of Dying" is an appropriate soundtrack.

Of all their albums, I certainly think that Led Zeppelin III is the Zeptemberist, mostly for its contemplative acoustic tracks, i.e. not "Immigrant Song." There is perhaps no song more beautiful in the vast Zeppelin canon than the gentle "That's The Way," which sounds like a mid-September sundown personified. Running a close second in that department is "Tangerine," which might be the band's one attempt at the country rock genre. It's a song that first grabbed me hard as a teenage romantic with an aching in his heart. Perhaps the thing I love best about Zeptember is the continuity, that more than twenty years later I can still enjoy something just as much as I did when I got my first taste. It's hard to say that about much of anything.

Of all the songs in their catalog, I associate "In the Light" from Physical Graffiti the most with Zepptember. The simple reason is that I bought it on CD after years of dallying during my first September in Michigan, and the old copy I purchased from a hole-in-the-wall used record store had disc 2 where disc 1 should have been. I put it on, expecting to hear the heavy, skanky riff of "Custard Pie," but was instead hit with a synthesizer imitating the eerie moans of an Irish horn. I instantly fell in love with the haunting sound and spent a couple of weeks playing it right when I got out of bed in the morning. To this day I associate this song with my earliest days as a visiting assistant professor, working eighty hours a week with music one of the few pleasures to afford myself.

There are other Zeppelin songs, many not necessarily well known, that I reserve for Zeptember, and others more famous I eschew, like "Whole Lotta Love," which speak more to spring's change of season and attendant libidinous awakening. Despite its subject matter, I think the classic b-side "Hey Hey What Can I Do" has an autumnal vibe. Perhaps its just the acoustic guitars, which sound like falling leaves in my head. Speaking of falling leaves, when all begins to wither and die around me, "In My Time of Dying" is an appropriate soundtrack.

Of all their albums, I certainly think that Led Zeppelin III is the Zeptemberist, mostly for its contemplative acoustic tracks, i.e. not "Immigrant Song." There is perhaps no song more beautiful in the vast Zeppelin canon than the gentle "That's The Way," which sounds like a mid-September sundown personified. Running a close second in that department is "Tangerine," which might be the band's one attempt at the country rock genre. It's a song that first grabbed me hard as a teenage romantic with an aching in his heart. Perhaps the thing I love best about Zeptember is the continuity, that more than twenty years later I can still enjoy something just as much as I did when I got my first taste. It's hard to say that about much of anything.

Tuesday, September 10, 2013

Twelve Years Later, We Still Live in the Nightmare

My memories of 9/11 are very fragmentary, but there is one thing I remember like it was yesterday. I heard the news over the radio at my desk in the TA office (I was a grad student at the time), and I all I could think was "many more people are going to die as a result of this." I knew in my gut right then that the attacks would be the beginning of an awful period.

In the fear and anxiety-ridden aftermath extreme expansions of the surveillance state like the PATRIOT Act and the creation of the Department of Homeland Security sailed through Congress virtually unopposed. America invaded Afghanistan, and then George W. Bush managed to use 9/11 as pretext for a war in Iraq, a nation that had absolutely nothing to do with the attacks. Paranoia struck deep everywhere, and for a time any criticisms of this state of affairs would be met with cries of "treason!" from the jingoistic brigade.

In those dark days I was lucky enough to see a 2004 BBC documentary series, The Power of Nightmares, which no TV outlet in America was willing to show. (A friend got on a free DVD that came with Wholphin magazine.) That series convincingly told a parallel history of neo-conservatism and radical Islamism, and argued that leaders like Blair and Bush needed to pump up the terrorist threat in order to legitimize their own power.

Of course, some things have changed, but the power of nightmares still holds sway. America is out of Iraq, bin Laden is dead, and our current president opposed the invasion of Iraq. However, he has continued the NSA's vast surveillance program, and is more than willing send out unmanned drones to rain death on those he has targeted, and others who just happen to be in the way. Plenty of people are still more than happy to sacrifice freedom when their government assures them it is necessary to ward off the boogeyman. Twelve years after the horrors of 9/11, its nightmare world still dominates our society. It's time for us to finally wake up.

In the fear and anxiety-ridden aftermath extreme expansions of the surveillance state like the PATRIOT Act and the creation of the Department of Homeland Security sailed through Congress virtually unopposed. America invaded Afghanistan, and then George W. Bush managed to use 9/11 as pretext for a war in Iraq, a nation that had absolutely nothing to do with the attacks. Paranoia struck deep everywhere, and for a time any criticisms of this state of affairs would be met with cries of "treason!" from the jingoistic brigade.

In those dark days I was lucky enough to see a 2004 BBC documentary series, The Power of Nightmares, which no TV outlet in America was willing to show. (A friend got on a free DVD that came with Wholphin magazine.) That series convincingly told a parallel history of neo-conservatism and radical Islamism, and argued that leaders like Blair and Bush needed to pump up the terrorist threat in order to legitimize their own power.

Of course, some things have changed, but the power of nightmares still holds sway. America is out of Iraq, bin Laden is dead, and our current president opposed the invasion of Iraq. However, he has continued the NSA's vast surveillance program, and is more than willing send out unmanned drones to rain death on those he has targeted, and others who just happen to be in the way. Plenty of people are still more than happy to sacrifice freedom when their government assures them it is necessary to ward off the boogeyman. Twelve years after the horrors of 9/11, its nightmare world still dominates our society. It's time for us to finally wake up.

Monday, September 9, 2013

Track of the Week: Peter Gabriel, "Games Without Frontiers"

I've been listening to a lot of Peter Gabriel lately, both his solo albums and his work with Genesis in the 70s. He's an artist who's sort of fallen through the cracks, perhaps because prog rock and 80s baby boomer rock are not genres with a great deal of staying power. He might be known better these days for the uses of his music in film, such as "In Your Eyes" in Say Anything, and "Solsbury Hill" in seemingly every trailer for a feel-good Hollywood movie.

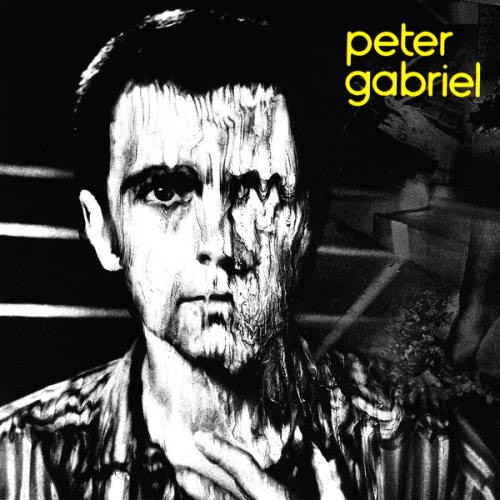

Gabriel's best record might well be his third self-titled record, sometimes referred to as "Melt" because of its disturbing cover. (Evidently the effect was produced by rubbing a Polaroid while it developed.) It came out in 1980, but sounds like something from much further into the decade. Certainly the use of metronomic beats, synthesizers, and gated drums would get rather pedestrian and overdone, but these effects were new at the dawn of the spandex decade. Instead of using these elements to make a poppy sound, Gabriel creates a mood of dread, perhaps no more pronounced than on "Games Without Frontiers." It has got to be one of the few catchy dirges to ever crack the charts.

The whole song is an allegory about war and great power politics, and treats them like schoolyard scrapes. While the meaning might be opaque, the whole point is that the games played by the generals and politicians on the global stage are childish and silly, but "if looks could kill they probably will." We're seeing some 'games without frontiers" being played out right now over Syria, which has this song on my mind.

Gabriel's best record might well be his third self-titled record, sometimes referred to as "Melt" because of its disturbing cover. (Evidently the effect was produced by rubbing a Polaroid while it developed.) It came out in 1980, but sounds like something from much further into the decade. Certainly the use of metronomic beats, synthesizers, and gated drums would get rather pedestrian and overdone, but these effects were new at the dawn of the spandex decade. Instead of using these elements to make a poppy sound, Gabriel creates a mood of dread, perhaps no more pronounced than on "Games Without Frontiers." It has got to be one of the few catchy dirges to ever crack the charts.

The whole song is an allegory about war and great power politics, and treats them like schoolyard scrapes. While the meaning might be opaque, the whole point is that the games played by the generals and politicians on the global stage are childish and silly, but "if looks could kill they probably will." We're seeing some 'games without frontiers" being played out right now over Syria, which has this song on my mind.

Saturday, September 7, 2013

Would a Syrian Intervention Be a "Stupid War"?

I was living in Illinois when the war in Iraq began, and I was so happy that one of the state's politicians, an up and coming state representative from Chicago named Barack Obama, had come out forcefully against it. The war made me sick to my stomach, from the lies used to promulgate it, the jingoist attacks on the Dixie Chicks and anyone else who dared to oppose it, to the thousands of lives snuffed out. As Obama took on national aspirations, his vocal opposition to the war was questioned, even after its failure and false pretenses were made manifest. (People forget just how awful the climate for dissent was back in 2003-2004.) He famously said that he was not opposed to all wars, only "stupid wars."

I thought that was a great statement at the time, not only because Iraq was a stupid war, but also because blanket pacifism is not a viable basis for this country's foreign policy. Obama's military actions in power, such as drone strikes, troop increases in Iraq and the bombing campaign in Libya, have surprised those who missed the second meaning of his "stupid wars" statement. That said, I have been increasingly alarmed by the continuation of these Bush-like policies when it comes to the "war on terror," especially drone strikes and the activities of the NSA.

The president clearly does not see these interventions, Syria included, as "stupid wars." The covert activities and drone strikes are meant to carry on the same old war against Al-Qaeda, but through different, less costly and risky means than invasion and regime change. He is pushing for action in Syria on wholly different grounds, namely to dissuade the Assad regime and other nations from using chemical weapons. Essentially, he is trying to enforce international norms through Bush-like methods of unilateralism.

The goal of these strikes is rather admirable, and reflects a kind of liberal interventionism now prominent in Obama's cabinet. In so many ways, it would be a far less stupid war than the war in Iraq. The United States would not be aiming for regime change, it would only be involved short term, and it is responded to a case of mass murder perpetuated by a horrible cruel regime. The war in Iraq was a naked imperialist adventure by the Bsuh administration to remake the Middle East to conform to a neo-con vision. The talk of weapons of mass destruction was never anything more than a pretense, rather than the real motivation in the case of Syria. Obama is not aiming to put a new regime in power, or to subject Syria to occupation.

A potentially open-ended intervention to unilaterally enforce an international norm isn't exactly inspiring the American people to action now, even though they got in lockstep behind the Iraq disaster. Of course, the fatigue from the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan perpetuated by Obama's predecessor has a lot to do with that. I also think that the horse sense of the public is actually right for a change, but perhaps not for the reasons I usually hear. The same conservatives who hurled abuse at me while I protested the war in Iraq ten years ago are now against intervention in the Middle East in large part due to their antipathy to the president. Most other people know little about the war in Syria, and the suffering that Syrian people have endured at the hands of the Assad regime. Unlike in 2003, they aren't scared of the boogeyman.

From where I stand, war in Syria would be stupid (namely), namely because it would, no matter how advanced our smart bombs are these days, lead to the deaths of innocent people. Their deaths would be all for the cause of the United States saving face after its president set a "red line" of behavior that the Assad regime broke. It will result in more, not less suffering by regular Syrians. It will not bring an end to that horrible war, and the rebels fighting Assad could end up being even worse (and Taliban-like) when they get into power, anyway. It would be stupid because it would be unilateral, and harm all the efforts Obama has made to patch up America's relationship with the rest of the world. It would continue to arouse the hostility of the people of the Middle East, who are tired of American political and military intervention. That hostility gives Al-Qaeda its foot soldiers. Any blowback will be worse than anything that might possibly be accomplished.

Perhaps the successful raid on bin Laden's compound and the bombing campaign in Libya have made the president over-confident about the capabilities of American force. I just hope he thinks about where he was and how he was thinking back in 2003, and somehow changes his mind about this stupid war.

Thursday, September 5, 2013

A Random Compendium of Lesser-Known Awesome Album Covers

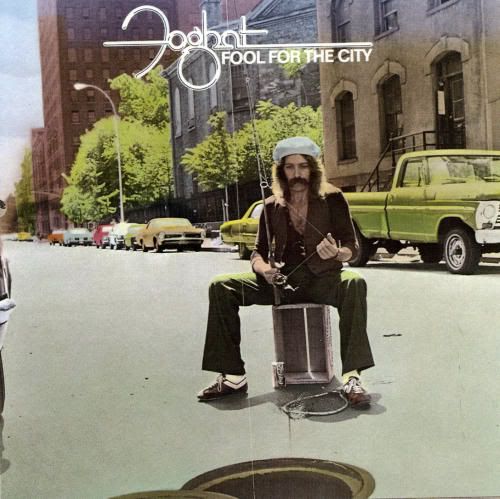

Foghat, Fool For the City

I just managed to pick this one up today, mostly for the cover, although I do have a guilty soft-spot for 70s 8 track Camaro music. I love the contrast of the urban scene with the rural past-time, and the mustachioed rocker look and solid steel cars that just scream 1975.

Porter Wagoner, The Bottom of the Bottle

Porter Wagoner is the king of gonzo country album covers, and this is his best. The record is a concept album about alcoholism, and the liner notes are written in the character of "Skid Row Joe," a character from one of the songs.

Willie Nelson, Good Times

We all know Willie Nelson as the braided, ganga-smoking country hippie. Before the 1970s, though, his image was a lot different. I can't imagine anything less counter-cultural than golf. Or the shoes that he's wearing in this picture. Maybe not a great cover in and of itself, but with the context of Willie's future in mind, I love it.

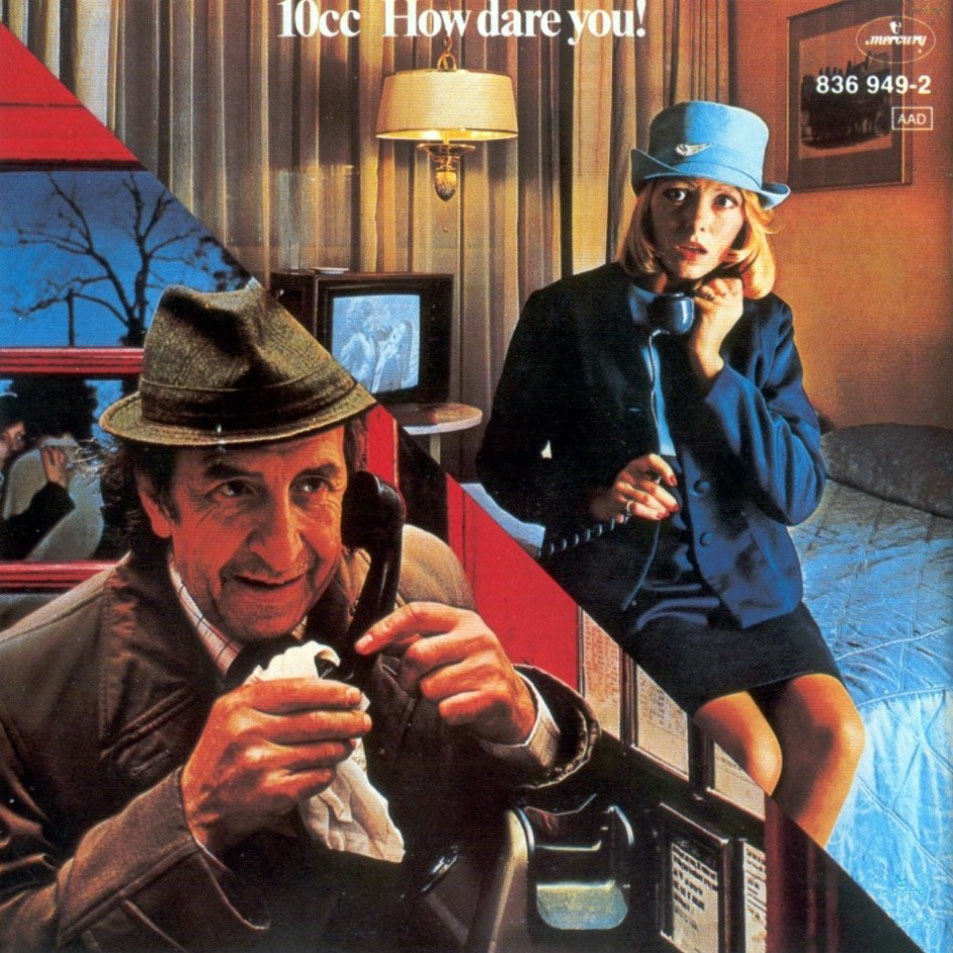

10cc, How Dare You

10cc were like the bastard child of prog rock and easy listening, as if Pink Floyd had collaborated with Barry Manilow. Speaking of the Floyd, the folks at Hipgnosis, who designed all of their famous album covers, also did this one for 10cc. The front cover is like a scene rom a soap opera. The back cover like something from a Benny Hill sketch:

The gatefold, however, is the best. It shows a bunch of people in a room all on the phone at the same time, and I take to be an oddly prophetic vision of the future.

Fleetwood Mac, Bare Trees

This is not only the best record of the Mac's post-Peter Green pre-Buckingham/Nicks early 70s period dominated by Bob Welch, but it has a lovely, haunting cover.

Peter Gabriel

Another Hipgnosis cover, this time on former Genesis frontman Peter Gabriel's first solo record. It is a picture that makes a statement, since Gabriel used to be known for his outlandish stage costumes. Here he is barely visible behind the windshield of a wet car in an image that captures the mundane despair of most daily life.

Wednesday, September 4, 2013

On Turning 38

I turned 38 today, which I find to be a deceptively momentous milestone. We usually mark the onset of middle-age at 40, but I think 38 is more meaningful to me, because it means I have now spent more time living outside of my parents' home than in it. When I turned 19, I had just started college, which now seems like a million ages ago. Since then I have lived in two different countries, five different states, and eight different cities. I earned three degrees, and worked for at least a year at five different jobs. A lot has changed, much more so than in the first 19 years of my life.

The dreams of my youth are mostly dead, but that's okay. I managed to become a professor, but that dream, to which I sacrificed many years, turned into a nightmare. I used to think of myself as a modern day Beatnik who would live a bohemian lifestyle forever. Nowadays I'm a family man with a wife and two kids, but they make me far happier than my old lifestyle of hanging out in bars and going to rock shows. If I went back in time to my 19 year-old self, he might think I am a sell-out for abandoning the bohemian path, and lame for ending up as a teacher, just like his mother and sister.

In the last 19 years, I've been forced to take the wisdom of my ancestors to heart, whether I wanted to or not. They lived through hard times and had their dreams crushed by the Depression, but managed to find contentment despite their poverty. The universe is indifferent to us and our aspirations, we must take heart in the small things that we can control. Changing the world comes not through revolutions, but in everyday, practical efforts to make it a better place to live in. The older I get, the more I appreciate Voltaire's Candide. At the end of the book, the title character finds peace not through visionary ideals, but by engaging himself in meaningful work. My days of sowing my wild oats are long gone, I am much happier doing as Candide, cultivating my garden. Call it getting soft or slowing down in middle-age, I think it's hard won wisdom.

The dreams of my youth are mostly dead, but that's okay. I managed to become a professor, but that dream, to which I sacrificed many years, turned into a nightmare. I used to think of myself as a modern day Beatnik who would live a bohemian lifestyle forever. Nowadays I'm a family man with a wife and two kids, but they make me far happier than my old lifestyle of hanging out in bars and going to rock shows. If I went back in time to my 19 year-old self, he might think I am a sell-out for abandoning the bohemian path, and lame for ending up as a teacher, just like his mother and sister.

In the last 19 years, I've been forced to take the wisdom of my ancestors to heart, whether I wanted to or not. They lived through hard times and had their dreams crushed by the Depression, but managed to find contentment despite their poverty. The universe is indifferent to us and our aspirations, we must take heart in the small things that we can control. Changing the world comes not through revolutions, but in everyday, practical efforts to make it a better place to live in. The older I get, the more I appreciate Voltaire's Candide. At the end of the book, the title character finds peace not through visionary ideals, but by engaging himself in meaningful work. My days of sowing my wild oats are long gone, I am much happier doing as Candide, cultivating my garden. Call it getting soft or slowing down in middle-age, I think it's hard won wisdom.

Monday, September 2, 2013

Five Songs To Hate Your Job To