Saturday, August 31, 2013

Track of the Week: Marshall Tucker Band, "Take the Highway"

Last weekend I had the good fortune to attend a friend's wedding down in Spartanburg, South Carolina. I had me a real good time, and got to see a lot of old friends in the bargain. I also learned that Spartanburg has rich a musical heritage for such a small town, including the Marshall Tucker Band. They were lesser known than more prominent Southern rockers of the 1970s like The Allman Brothers Band, but had their share of great songs.

My friend Brian was with me this weekend, and he has long tried to change my mind about Southern rock. I am a lover of much of the South's musical heritage, such as the blues, R&B, bluegrass, rockabilly, and (classic) country. However, I'd long been wary of Southern rock, mostly because the people in my hometown who listened to it tended to be the Nebraska equivalent of the dopes on the Jersey Shore: boorish lowlife ingrates.

That said, thanks to Brian I have really developed a love for the Allman Brothers, mostly because they might meld jazz to rock better than any other band that's ever been. The Marshall Tucker Band could do that well too, as evidenced by "Take the Highway." It's got a great, folk-rock riff with jazzy flute laid over the top, not the kind of thing one stereotypically expects from a band hailing from a small town in the Carolina piedmont. There's also a loose, jazzy, jammy structure that shows off the band's musicianship. Overall, it has the same level of craft and instrumental complexity as your average Rush record, but is a helluva lot funkier and less pretentious. If you're ever driving down a backwoods highway through the pines, put it on and prepare to be entranced.

Thursday, August 29, 2013

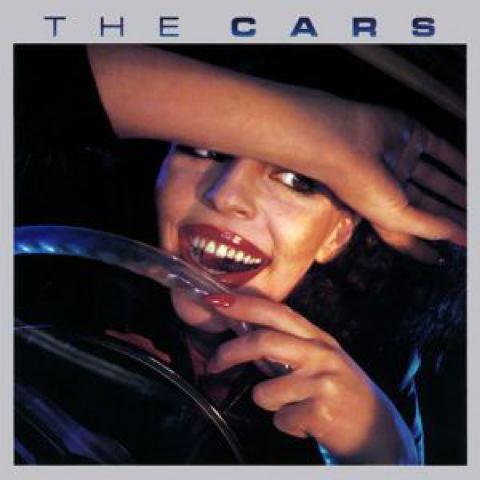

Classic Albums: The Cars

There are precious few records that can be called "all killer, no filler," and The Cars' debut album is certainly one of them. While they had more and bigger hits later in their career, they never put together a single album as good as this one.

They are a band that has faded from popular consciousness, in large part because like a power-forward with a hot outside shot, they're tweeners who can't be easily categorized. The Cars are one of the few bands that have a foot in New Wave and in classic hard rock. Their use of synthesizers and their tight, power-poppy tunes fit right in with the punk/New Wave trends of the late 1970s, but their heavy, straight-ahead riffs are more Foreigner than Elvis Costello.

On The Cars, that combination is as glorious as peanut butter and chocolate, gin and vermouth, or Tango and Cash. The meld of rock tradition with New Wave innovation is apparent on the first track, "Let the Good Times Roll." It starts with a riff that sounds like the blues, but as played by one of Kraftwerk's robots. The song title recalls classic R&B, but Ric Ocasek's voice is as angular as his face. From there the album segues into "My Best Friend's Girl," which has a 1950s rock theme and retro organ triplets paired with modern synths and a liquid guitar solo.

Just when you thought the band couldn't top that one-two punch, up comes "Just What I Needed," a gloriously catchy power-pop number that still invigorates every time I hear it. It's more on the New Wavey side, with the faux British pronunciation of "perfume that you wear" and the synthesizer riff between the verses. That last two songs on side one, "I'm In Touch With Your World" and "Don't Cha Stop" can't match this brilliance, but they do bring in nervy New Wave rhythms and an artier touch than the poppy tracks that start the album. It's hard to find many records what have a better side one.

Side two tempers the rocking rave-up with fraught emotions. The first song, "You're All I've Got Tonight," is about crawling back to a bad ex out of loneliness and sexual need. The guitar gets skanky and Ocasek drops the arty pose for some cutting anger. The temperature keeps rising on "Bye Bye Love." Again, the title recalls old time rock and roll (the Everly Brothers, in this case) but the song has got punky edge and an epically cool descending synth/guitar hook.

At that point, the tempo slows for the album's end. "Living in Stereo" is a moody, minor-key track that sounds like a refugee from the Talking Heads' Fear of Music album. Things end with the emotionally tumultuous "All Mixed Up," leaving the listener in a very different place from where the good times are rolling. All in all, this is a record that moves from peak to peak so effortlessly that you would never believe that it's a debut album.

The Cars' straddling of hard rock and New Wave may have allowed them to be overlooked or underrated, but they were able to put together a record jam packed with more memorable songs than many acts produce in their lifetimes. They did it all by bringing different genres together and playing to the strengths of both. It's something more artists ought to be doing nowadays.

Wednesday, August 28, 2013

The Brilliant Insight of Veep

Television has been revolutionized in the past decade by innovative new adult dramas like The Sopranos, Breaking Bad, and Mad Men, among others. However, some genres still needed shaking up, especially shows taking place in a political setting. For years I have failed to ever see a film or television show about politics that rang true in any way.

There are people who stand by The West Wing, but it bears as much resemblance to the reality of politics as I do to Ethel Merman. None of the politicians in the show, especially the saintly president Bartlett, appear to be motivated by anything other than their ideals. There are ridiculous soap opera plots, like the kidnapping of the president's daughter, the president being incapacitated, etc. The West Wing echoes older visions of Washington, like Frank Capra's Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, where good-hearted pols fight and win against entrenched interests and unscrupulous opponents. The characters of West Wing are fundamentally good people with the public's interest in mind and the whole enterprise just drips with sugary-sweet sentiment. Whenever I tried to watch this show, I laughed my ass off.

A more recent show that I find to be equally laughable is House of Cards. It takes a completely different approach showing a Washington full of back-stabbing and intrigue. In this version, our politicians are not dewey-eyed do-gooders, but malicious power-mad manipulators. This version of American politics is just as silly. It turns all of our half-assed, idiotic political leaders into criminal masterminds.

Our political class is not made up of super-villains nor knights in shining armor. As far as I can tell, it is full of narcissistic, venal, short-sighted, and incompetent careerists. I recently read Mark Leibovich's alternately funny and infuriating new book This Town, which pulls back the curtain behind the world of Washington insiders. The political class, which includes journalists, flacks, hacks, lobbyists and operatives as much as it does politicians themselves, comes across as ridiculously egotistical and disconnected from the rest of America. Just imagine an entire world full of the Type A brown-noser who got elected class president at your school. Washington is neither the font of virtue we sometimes see portrayed on the screen, nor is it a land of malicious puppet-masters. No, it's a colony of self-centered, bumbling assholes.

While the situations in Veep aren't exactly true to life, it really nails the ethos of Washington's political class, and its priorities. Selena Meyer's staff frets over what kind of frozen yogurt to buy at a photo-op, so as to send the right message. The liason to the president is an insufferable turd, but his proximity to higher power means that others must curry favor with him. Any attempt at passing legislation gets shredded by special interets, and at the end of the day, Meyer is more worried about how the failure of her pet initiatives hurts her image than anything else. Nobody seems to care at all about the public good; keeping donors happy and maintaining a high media profile are far more important. With a thoroughly useless and inept Congress constantly threatening to shut down the government or hold the debt ceiling hostage, Veep is definitely a sign of the times, and a funny one at that.

While the situations in Veep aren't exactly true to life, it really nails the ethos of Washington's political class, and its priorities. Selena Meyer's staff frets over what kind of frozen yogurt to buy at a photo-op, so as to send the right message. The liason to the president is an insufferable turd, but his proximity to higher power means that others must curry favor with him. Any attempt at passing legislation gets shredded by special interets, and at the end of the day, Meyer is more worried about how the failure of her pet initiatives hurts her image than anything else. Nobody seems to care at all about the public good; keeping donors happy and maintaining a high media profile are far more important. With a thoroughly useless and inept Congress constantly threatening to shut down the government or hold the debt ceiling hostage, Veep is definitely a sign of the times, and a funny one at that.

Monday, August 26, 2013

An Amateur Ethnography of My Grad School Tribe

I haven't been writing for the last few days because I was down in South Carolina at a friend's wedding. Some of my grad school friends were there, and I saw some more in North Carolina and Virginia on the way home. I was very fortunate to fall in with a great group of people in grad school at Big Ten University who made my time there some of the best years of my life. Somewhere on the New Jersey Turnpike today, I realized that an analysis of our experiences might help illuminate the problems facing young(ish) scholars today.

There are eight people in the cohort I am analyzing, counting myself. Seven of us have PhDs, and another is going to be defending this semester. Six of the eight have degrees in history, one in English, and one in computer science. Five of us are still employed in academia, although we all were professors at some point. I have left to be a private school teacher, another is doing political advocacy and studying to be a social worker, and another works as a researcher. Of the five in academia, three are tenured/tenure track, and two are in full-time contingent positions with a measure of job security. Of the three who are in tenurable positions, one works at a regional state university with onerous workloads, another at a SLAC, and another at a SLAC with a research-friendly workload. Essentially, only one of eight of us got the kind of job that our grad school mentors prepared us for.

Since I don't want to single any of my friends out (some of whom read this blog regularly), I'll just talk about our experiences and feelings collectively, based on the conversations I've had this weekend. There are a few things that stick out. In the first place, there is an almost universal feeling of letdown, as far as academia is concerned. This even includes those who managed to get the brass ring of the tenure-track job. Of the three people who are no longer in academia, two of us were well on our way to getting tenure, and decided to walk away. Three of the five people who are still professors talked seriously with me about leaving the profession in the near future themselves.

These numbers might be explained by the general feeling that academic work is poorly paid, highly insecure, and forces those who take it to live in places that they don't really want to live in. This last factor was an important one for all of those who left academia, and something that bears more conversation. Academia is like the priesthood, in that the vast majority of scholars have little to no control over where they will be able to find full time work. That's why I ended up in a wretched East Texas town, and many others I know are living in benighted rural burgs that they never would have chosen to live in if they had not been professors. This is a major quality of life issue that grad school mentors tend to gloss over, because if more grads were aware of just how little freedom they would have to choose where they live, they wouldn't bother to finish their studies.

It was so great to see everyone again, but bittersweet to see so many people with so much to offer given so little opportunity and reward by the profession that they have sacrificed so much to be a part of. If more folks out there would do an amateur ethnography of their grad school circle of friends, I bet they'll uncover some similar things.

There are eight people in the cohort I am analyzing, counting myself. Seven of us have PhDs, and another is going to be defending this semester. Six of the eight have degrees in history, one in English, and one in computer science. Five of us are still employed in academia, although we all were professors at some point. I have left to be a private school teacher, another is doing political advocacy and studying to be a social worker, and another works as a researcher. Of the five in academia, three are tenured/tenure track, and two are in full-time contingent positions with a measure of job security. Of the three who are in tenurable positions, one works at a regional state university with onerous workloads, another at a SLAC, and another at a SLAC with a research-friendly workload. Essentially, only one of eight of us got the kind of job that our grad school mentors prepared us for.

Since I don't want to single any of my friends out (some of whom read this blog regularly), I'll just talk about our experiences and feelings collectively, based on the conversations I've had this weekend. There are a few things that stick out. In the first place, there is an almost universal feeling of letdown, as far as academia is concerned. This even includes those who managed to get the brass ring of the tenure-track job. Of the three people who are no longer in academia, two of us were well on our way to getting tenure, and decided to walk away. Three of the five people who are still professors talked seriously with me about leaving the profession in the near future themselves.

These numbers might be explained by the general feeling that academic work is poorly paid, highly insecure, and forces those who take it to live in places that they don't really want to live in. This last factor was an important one for all of those who left academia, and something that bears more conversation. Academia is like the priesthood, in that the vast majority of scholars have little to no control over where they will be able to find full time work. That's why I ended up in a wretched East Texas town, and many others I know are living in benighted rural burgs that they never would have chosen to live in if they had not been professors. This is a major quality of life issue that grad school mentors tend to gloss over, because if more grads were aware of just how little freedom they would have to choose where they live, they wouldn't bother to finish their studies.

It was so great to see everyone again, but bittersweet to see so many people with so much to offer given so little opportunity and reward by the profession that they have sacrificed so much to be a part of. If more folks out there would do an amateur ethnography of their grad school circle of friends, I bet they'll uncover some similar things.

Thursday, August 22, 2013

Track of the Week: Pulp, "Mile End"

From about 1995 to 1998, most of the new music listen I listened to came from the British Isles. During that time Blur, Suede, Oasis, Radiohead, Portishead, and The Verve put out some amazing stuff that also got airplay on American alternative rock radio. Pulp, on the other hand, were so British that they translated poorly to these shores, which made me love them all the more. While Oasis, The Verve, and Radiohead blasted along with heavy guitars that reflected grunge's dominance, Pulp had a sound like cabaret filtered through 80s New Wave with a dash of The Smiths. As time has gone by and the 90s are receding like my hairline into the realm of memory, Pulp comes out looking a lot more relevant and less dated than the likes of Oasis.

Lead singer Jarvis Cocker didn't write conventional rock songs. He sang a lot about sex, but told stories of unhealthy obsession and embarrassment, not cock-rocking bedroom conquest. Cocker also spun tales of mundane adventures in the everyday world. "Dishes" is about washing the dishes as an act of love and self-reflection. "Sorted Out for E's and Whizz" relates the horror story of going to a rave gone wrong, complete with bad drugs. "Mile End," from the 1996 cinematic masterpiece Trainspotting, describes living in a cheap apartment in a crummy building, and does so in exacting detail. There's the piss in the elevator, constant fish smell, and ruffians making a violent racket. There aren't many rock bands who would bother writing about such a thing, much less so poetically.

Anybody who's had the experience knows what it's like. I always associate this song with the Chicago apartment my buddy Dave had until we lived together. The halls of the building looked like a cheap, hourly rate motel and smelled like burnt hair, and his unit was a tiny studio with godawful rust-colored shag carpeting straight out of 1973. Because of that, and the fact that we both loved Trainspotting, with this being among his favorite songs on the soundtrack, I have a hard time listening to it these days. He died suddenly last December, and every time I hear a song or see a movie that we would enjoy together, it just rips my heart out. It's just the kind of thing that Jarvis Cocker and Pulp could make a song about.

Tuesday, August 20, 2013

Letting the Mask Drop a Little

When I first started blogging back in 2004, I did it under my own name, and didn't start hiding my identity until about 2007 or so. Being on the academic job market at the time meant that I was wary of having my blog used against me, and so I figured it was best to create a secret identity to protect myself. I am now beginning to think that maintaining my anonymity is a little cowardly and also a drag on my writing. Sheltering behind a persona has made it easier for me to express my true thoughts and emotions, but it has also been too easy to angrily vent my spleen and not consider my words. I'm keeping my Werner Herzog's Bear handle, partly because that's how most folks online know me, and party because I've always been proud of it. However my official name can be found on the sidebar, for anyone who's actually interested. To all my friends whom I've scolded in the past about connecting my name to the blog on social media, don't sweat it anymore. I figure if people are going to love or hate what is written here, they ought to know who's doing the talking.

The Royals, A-Rod, and the End of the Steroid Era

Baseball has a talent for letting its drama and foibles overwhelm its public image. Everyone's talking about A-Rod, not the resurgence of once moribund franchises like the Royals and Pirates, or the amazing feats of Miguel Cabrera, who is on his way to being one of the all time greats. Compare this to the NFL. Aaron Hernandez is accused of murder -a crime slightly more heinous than injecting steroids- but conversation in the football world is much more centered on the field than off. Some of this might have to do with the weird and outdated expectations of purity among baseballers representing the sainted National Past-Time.

Be that as it may, the current A-Rod saga (and Ryan Braun sideshow) is merely the last, strained coda of baseball's Steroid Era. Of course, plenty of players are still juicing and will continue to do so, but the way baseball is played has definitively changed, and that has benefitted certain teams and hurt others. For evidence, look no further than the Kansas City Royals. At the start of the 2012 season, I wrote a long piece about their epic futility over the last twenty years, and there seemed to be little hope of a rebound. This year they are winning and in contention for a possible play-off spot. They are also winning in ways that pre-steroid era teams won. As a great piece at Grantland demonstrates, the key to this team's success has been pitching assisted by stellar defense. It certainly hasn't been home runs, since the Royals have only hit 84 this season, the lowest total in the American League.

This Royals team reminds me of the Cardinals of the 1980s, who were one of the top squads of the era, but hit few homers. Now that the Steroids Era is over and pitching is ascendant (just look at the number of no-hitters in recent years), pitching, fielding, and base-running are much more important components of the game. This Royals team has weaknesses, but their strengths are strengths that play to the trends in the game. Even Kaufman Stadium itself symbolizes their throwback methodology. The Royals play in a big, pitcher-friendly park of the kind totally foreign to the homer-friendly bandboxes built around the league in the 1990s and early 2000s.

It's not just the Royals, either. The Pirates, a team perhaps even more perennially disappointing to their faithful for the past two decades, are leading their division with a similar model. They rank 11th in the National League in runs scored, but first in ERA. The Dodgers, who are just killing their competition right now, are ranked 12th in home runs in the National League. Of course, there are teams like the Braves who are winning with the long ball, but the contours of the game have made other paths to winning easier. Sluggers like Miguel Cabrera still stalk the earth, but the best player in the senior circuit just might be the Pirates' Andrew McCutcheon, a great all-around player who can hit for modest power, high average, steal bases, and patrol center field.

All of this means that the average baseball game is more exciting and interesting than it was fifteen years ago at the heigh of homer mania. Daring base running and stellar fielding are great things to watch. Fewer homers makes them that much more exciting when they happen. On a more personal note, the Mets are rebuilding their team around strong pitching and timely hitting, and the success of the Pirates and Royals gives me hope for my newly adopted squad. The fact that the shift in the game has led to longtime doormats getting back into contention and shaking things up is reason enough to welcome it.

Be that as it may, the current A-Rod saga (and Ryan Braun sideshow) is merely the last, strained coda of baseball's Steroid Era. Of course, plenty of players are still juicing and will continue to do so, but the way baseball is played has definitively changed, and that has benefitted certain teams and hurt others. For evidence, look no further than the Kansas City Royals. At the start of the 2012 season, I wrote a long piece about their epic futility over the last twenty years, and there seemed to be little hope of a rebound. This year they are winning and in contention for a possible play-off spot. They are also winning in ways that pre-steroid era teams won. As a great piece at Grantland demonstrates, the key to this team's success has been pitching assisted by stellar defense. It certainly hasn't been home runs, since the Royals have only hit 84 this season, the lowest total in the American League.

This Royals team reminds me of the Cardinals of the 1980s, who were one of the top squads of the era, but hit few homers. Now that the Steroids Era is over and pitching is ascendant (just look at the number of no-hitters in recent years), pitching, fielding, and base-running are much more important components of the game. This Royals team has weaknesses, but their strengths are strengths that play to the trends in the game. Even Kaufman Stadium itself symbolizes their throwback methodology. The Royals play in a big, pitcher-friendly park of the kind totally foreign to the homer-friendly bandboxes built around the league in the 1990s and early 2000s.

It's not just the Royals, either. The Pirates, a team perhaps even more perennially disappointing to their faithful for the past two decades, are leading their division with a similar model. They rank 11th in the National League in runs scored, but first in ERA. The Dodgers, who are just killing their competition right now, are ranked 12th in home runs in the National League. Of course, there are teams like the Braves who are winning with the long ball, but the contours of the game have made other paths to winning easier. Sluggers like Miguel Cabrera still stalk the earth, but the best player in the senior circuit just might be the Pirates' Andrew McCutcheon, a great all-around player who can hit for modest power, high average, steal bases, and patrol center field.

All of this means that the average baseball game is more exciting and interesting than it was fifteen years ago at the heigh of homer mania. Daring base running and stellar fielding are great things to watch. Fewer homers makes them that much more exciting when they happen. On a more personal note, the Mets are rebuilding their team around strong pitching and timely hitting, and the success of the Pirates and Royals gives me hope for my newly adopted squad. The fact that the shift in the game has led to longtime doormats getting back into contention and shaking things up is reason enough to welcome it.

Sunday, August 18, 2013

More on Academic Lifeboaters

My recent post on academic lifeboaters has received a lot of traffic, thanks to Pan Kisses Kafka's kind referral and the Twitterverse. Sadly, it might be yet another example of how my best writing comes out of pain and rage, since the post was prompted by reading the vapid cant of meritocrats and lifeboaters in the comments sections of post-academic bloggers. Now I am out of academia and much happier, my writing is suffering since there are fewer things to trigger outbursts of my sharper prose. I guess that's a small price to pay for mental health and spiritual contentment.

I had a very rude reminder of my former anguish a couple of nights ago, when I had a dream that I was still on the academic job market. It was so utterly convincing that I woke up in an absolute panic, it took me about twenty minutes to settle down and fall back to sleep. (Normally I go right back to sleep after a bad dream.) I was on the market for a total of six grueling, painful years when I lived in a constant state of uncertainty about my future. It took me three shots to get a tenure-track job, and I tried (and failed) three more times to escape the horror show at my tenure-track job before finding happiness as a teacher.

Ever since my earliest youth I have had a mortal fear of rejection and judgement, much of which could be chalked up to my fervently Catholic upbringing. Still to this day if I screw something up I will sit and think about obsessively for days on end. The academic job market is one long train of judgement and rejection, with plenty of opportunities for screw-ups and mistakes to beat myself up over. Dante could not have devised a more effective personal hell for me to live in. Every year about this time when I was on the job market a knot would develop in my stomach that would get progressively tighter and tighter until spring. So many weekends and nights were spent assembling applications that cost money and time that I didn't have, and many of them never received a reply in return. At the point in my career when I had the most qualifications (book contract, three articles in top journals, several courses developed) I started getting the fewest responses. All of the years of work and sacrifice and playing by the rules of the profession seemed to amount to nothing, and the rejection was just making me insane. To go back to that would be the worst nightmare of them all.

It's when I think about the job market that my anger towards the lifeboaters gets most intense. Anyone who's been through the gauntlet of fire ought to know how unfair and random it is, and how much luck plays into it. To sit back and belch "meritocracy!" when the fairness of the system is challenged requires an immense amount of self-delusion, narcissism, or both.

But I need to let the anger and rage subside. I now work at a place where I am greatly appreciated and well-rewarded. The experience has taught me the truth of the post-academic mantras I repeat to myself when the feelings of rejection and anger flare up: I am not a failure, the academic profession is failure. I was not rejected, I made the right decision to reject it. The profession doesn't get to judge me, I have judged it, and found it to be wanting.

The lifeboaters can have their miserable shipwreck, I've got better things to do.

I had a very rude reminder of my former anguish a couple of nights ago, when I had a dream that I was still on the academic job market. It was so utterly convincing that I woke up in an absolute panic, it took me about twenty minutes to settle down and fall back to sleep. (Normally I go right back to sleep after a bad dream.) I was on the market for a total of six grueling, painful years when I lived in a constant state of uncertainty about my future. It took me three shots to get a tenure-track job, and I tried (and failed) three more times to escape the horror show at my tenure-track job before finding happiness as a teacher.

Ever since my earliest youth I have had a mortal fear of rejection and judgement, much of which could be chalked up to my fervently Catholic upbringing. Still to this day if I screw something up I will sit and think about obsessively for days on end. The academic job market is one long train of judgement and rejection, with plenty of opportunities for screw-ups and mistakes to beat myself up over. Dante could not have devised a more effective personal hell for me to live in. Every year about this time when I was on the job market a knot would develop in my stomach that would get progressively tighter and tighter until spring. So many weekends and nights were spent assembling applications that cost money and time that I didn't have, and many of them never received a reply in return. At the point in my career when I had the most qualifications (book contract, three articles in top journals, several courses developed) I started getting the fewest responses. All of the years of work and sacrifice and playing by the rules of the profession seemed to amount to nothing, and the rejection was just making me insane. To go back to that would be the worst nightmare of them all.

It's when I think about the job market that my anger towards the lifeboaters gets most intense. Anyone who's been through the gauntlet of fire ought to know how unfair and random it is, and how much luck plays into it. To sit back and belch "meritocracy!" when the fairness of the system is challenged requires an immense amount of self-delusion, narcissism, or both.

But I need to let the anger and rage subside. I now work at a place where I am greatly appreciated and well-rewarded. The experience has taught me the truth of the post-academic mantras I repeat to myself when the feelings of rejection and anger flare up: I am not a failure, the academic profession is failure. I was not rejected, I made the right decision to reject it. The profession doesn't get to judge me, I have judged it, and found it to be wanting.

The lifeboaters can have their miserable shipwreck, I've got better things to do.

Friday, August 16, 2013

Track of the Week: Genesis, "Dancing With the Moonlit Knight"

Coming of musical age in the 1980s, I thought of Genesis as a Phil Collins side project, and Peter Gabriel as the most cutting-edge artist outside of Prince to get regular Top 40 airplay. One day I saw something on MTV that referenced Genesis' history that showed Peter Gabriel fronting the band in the mid-1970s wearing some kind of crazy costume like the guys in the Fruit of the Loom ads. The music was absolutely wild, a million miles away from polished, straight-ahead pop rock like "Invisible Touch" or world music inflected tracks like "In Your Eyes." I was intrigued, but never explored vintage Genesis because I soon became too punk rock to be caught listening to prog.

Years later, living in Grand Rapids, I had access to a fantastic library, and checked out Genesis' Selling England By the Pound album on a lark, and was immediately entranced. It opens with "Dancing With the Moonlit Night," which starts with Gabriel mournfully keening "Can you tell me where my country lies?" The song references Britain's economic and political turmoil of the 1970s, but does it in a very different fashion than the later punk rock thrashings of the Sex Pistols. Instead of three chords and a cloud of dust over two minutes, we get operatic dynamics, time-signature changes, and extended soloing over eight minutes. It's a rousing, beautiful song that's one of the great moments of ecstasy that make prog's pretentions and preciousness worth wading through. Listen to the whole album, you won't be disappointed.

Thursday, August 15, 2013

Analyzing the New Jersey Senate Race

This week a very small number of New Jersey voters cast their ballots in a special primary election for the deceased Frank Lautenberg's seat in the US Senate. Bad weather and summer vacations helped account for the low turnout, as well as a sense that Corey Booker and Steve Lonegan would be the inevitable nominees on route to a Booker landslide in October.

That fact itself says a lot. In the first place, it shows Booker's megawatt star power in the Garden State, since he had to run against a pretty formidable group of politicians: Rush Holt, Sheila Oliver, and Frank Pallone. The latter had the Lautenberg family's endorsement, Holt was the most progressive and experienced in Washington, and Oliver is the Speaker of the state's General Assembly. Any one of the losing candidates would have been a tough opponent for Chris Christie, who the Democrats are so afraid of that no one of Oliver, Pallone, or Holt's stature dared run against him. Booker has been a rising star for some time in the Democratic Party, despite his cozy relationships with Wall Street and Chris Christie, embrace of education "reform," and cold-shouldering of the labor movement. While I am mostly happy with the job he has done here in Newark and will be voting for him in the fall, I think many New Jersey Democrats will ultimately be disappointed with the stances he will take in Washington. Booker has earned a progressive reputation for vocally defending food stamps and gay rights, but he is in actuality a lot more moderate than both his supporters and opponents realize.

There is not one shred of moderation in Steve Lonegan, Booker's Republican opponent. He is a conservative, Tea Party firebrand who is so far to the right that his campaign has the potential to embarrass the New Jersey GOP. Lonegan is rabidly anti-abortion, staunchly pro-gun, has blamed "government regulation" for Camden's deindustrialization, blames gridlock in Congress on "the president's insistence on forcing his far-left liberal agenda on the country," called for the repeal of the Affordable Care Act, supports a flat tax, praised Romney's 47% comments, and has even downplayed the suffering of Hurricane Sandy victims in his own state.

This is the Garden, not the Lone Star State, however, and while a man like Lonegan would be a shoo-in in Texas, here in Jersey Tea Party conservatism is a fringe phenomenon. I am sure the Republican party is happy to throw a bone to their resident wing-nuts to keep them happy and obedient, but Chris Christie has already said he is not campaigning for Lonegan. You could chalk much of this up to Christie's legendary pettiness and score-settling. Lonegan ran a contentious primary against Christie in the 2009 governor's race, and there's nothing that Governor Bully loves more than crushing anyone who dares to criticize him. I also see in this decision not to get behind Lonegan Christie' deft game of staying popular in a left-leaning state by making friends with popular Democrats like Booker while distancing himself from Sun Belt-style conservatives.

Lonegan is really more of an activist than a politician and actually has very little experience in government. His one stint in public office was as mayor of Bogota, a borough of merely eight thousand souls in Bergen County. He has run unsuccessfully for statewide office on several occasions, but got his lucky break this year when no one of any stature in the state GOP cared to go up against Booker's juggernaut. A buffoon with a tiny amount of actual political experience, Lonegan is a poster child for white male privilege.

Like other recent Tea Party candidates (Christine O'Donnell, Todd Aiken, etc.) Lonegan has already made a fool out of himself, both with his opinions and with his behavior. In the waning days of the primary, his Twitter feed featured this image, intending to mock Booker's foreign policy knowledge:

In case you don't know, a majority of Newark's residents are African-American, and there is a large Brazilian and Portuguese immigrant population in East Ward (and also from many other nations not listed here). I am not sure what this image is trying to say, other than to imply that the residents of Newark are foreigners and not "real Americans" on the basis of their race and ethnicity, or that Booker, a graduate of Stanford and Yale, is some kind of imbecile. In either case, the bigotry behind this "joke" is pretty transparent. Lonegan made matters worse for himself in his response, which was to blame a staffer, and then call the criticism of this tweet overwrought "political correctness," as if demeaning the residents of the largest city in the state he will supposedly "represent"is a small matter. My time in New Jersey has taught me that white conservatives in this state, its governor included, view Newark and its people with absolute revulsion and contempt. Lonegan seemed to forget that Twitter is not his suburban barbershop.

That prevailing opinion among white New Jersey conservatives might help explain why he was able to get 80% of the Republican vote even after such shameful behavior. At least I no longer live in Texas, where Tea Party maniacs like Lonegan beat moderate Democrats like Booker for statewide office every time. I am glad to be here in New Jersey, where racial resentment and the Tea Party are sadly present, but on the outside looking in. That said, the fact that a man like Steve Lonegan can get nominated to run for Senator by a major party is pretty depressing.

That fact itself says a lot. In the first place, it shows Booker's megawatt star power in the Garden State, since he had to run against a pretty formidable group of politicians: Rush Holt, Sheila Oliver, and Frank Pallone. The latter had the Lautenberg family's endorsement, Holt was the most progressive and experienced in Washington, and Oliver is the Speaker of the state's General Assembly. Any one of the losing candidates would have been a tough opponent for Chris Christie, who the Democrats are so afraid of that no one of Oliver, Pallone, or Holt's stature dared run against him. Booker has been a rising star for some time in the Democratic Party, despite his cozy relationships with Wall Street and Chris Christie, embrace of education "reform," and cold-shouldering of the labor movement. While I am mostly happy with the job he has done here in Newark and will be voting for him in the fall, I think many New Jersey Democrats will ultimately be disappointed with the stances he will take in Washington. Booker has earned a progressive reputation for vocally defending food stamps and gay rights, but he is in actuality a lot more moderate than both his supporters and opponents realize.

There is not one shred of moderation in Steve Lonegan, Booker's Republican opponent. He is a conservative, Tea Party firebrand who is so far to the right that his campaign has the potential to embarrass the New Jersey GOP. Lonegan is rabidly anti-abortion, staunchly pro-gun, has blamed "government regulation" for Camden's deindustrialization, blames gridlock in Congress on "the president's insistence on forcing his far-left liberal agenda on the country," called for the repeal of the Affordable Care Act, supports a flat tax, praised Romney's 47% comments, and has even downplayed the suffering of Hurricane Sandy victims in his own state.

This is the Garden, not the Lone Star State, however, and while a man like Lonegan would be a shoo-in in Texas, here in Jersey Tea Party conservatism is a fringe phenomenon. I am sure the Republican party is happy to throw a bone to their resident wing-nuts to keep them happy and obedient, but Chris Christie has already said he is not campaigning for Lonegan. You could chalk much of this up to Christie's legendary pettiness and score-settling. Lonegan ran a contentious primary against Christie in the 2009 governor's race, and there's nothing that Governor Bully loves more than crushing anyone who dares to criticize him. I also see in this decision not to get behind Lonegan Christie' deft game of staying popular in a left-leaning state by making friends with popular Democrats like Booker while distancing himself from Sun Belt-style conservatives.

Lonegan is really more of an activist than a politician and actually has very little experience in government. His one stint in public office was as mayor of Bogota, a borough of merely eight thousand souls in Bergen County. He has run unsuccessfully for statewide office on several occasions, but got his lucky break this year when no one of any stature in the state GOP cared to go up against Booker's juggernaut. A buffoon with a tiny amount of actual political experience, Lonegan is a poster child for white male privilege.

Like other recent Tea Party candidates (Christine O'Donnell, Todd Aiken, etc.) Lonegan has already made a fool out of himself, both with his opinions and with his behavior. In the waning days of the primary, his Twitter feed featured this image, intending to mock Booker's foreign policy knowledge:

In case you don't know, a majority of Newark's residents are African-American, and there is a large Brazilian and Portuguese immigrant population in East Ward (and also from many other nations not listed here). I am not sure what this image is trying to say, other than to imply that the residents of Newark are foreigners and not "real Americans" on the basis of their race and ethnicity, or that Booker, a graduate of Stanford and Yale, is some kind of imbecile. In either case, the bigotry behind this "joke" is pretty transparent. Lonegan made matters worse for himself in his response, which was to blame a staffer, and then call the criticism of this tweet overwrought "political correctness," as if demeaning the residents of the largest city in the state he will supposedly "represent"is a small matter. My time in New Jersey has taught me that white conservatives in this state, its governor included, view Newark and its people with absolute revulsion and contempt. Lonegan seemed to forget that Twitter is not his suburban barbershop.

That prevailing opinion among white New Jersey conservatives might help explain why he was able to get 80% of the Republican vote even after such shameful behavior. At least I no longer live in Texas, where Tea Party maniacs like Lonegan beat moderate Democrats like Booker for statewide office every time. I am glad to be here in New Jersey, where racial resentment and the Tea Party are sadly present, but on the outside looking in. That said, the fact that a man like Steve Lonegan can get nominated to run for Senator by a major party is pretty depressing.

Tuesday, August 13, 2013

Five Best 70s Outlaw Country Songs

As all y'all can probably tell from my "Track of the Week" selections recently, I've been listening to a lot of classic country music these days. That musical itch also pushed me to pick up Michael Streissguth's book Outlaw: Waylon, Willie, Kris, and the Renegades of Nashville, a look at the "outlaw country" movement of the 1960s and 1970s. Reading that book is a reminder that conflicts over the nature of country music between the twin poles of "pop" and "traditional" have been with us for quite some time. Since at least Garth Brooks, the "pop" side has dominated country music to the point that Tom Petty has aptly described it as "bad rock with a fiddle." That had a lot to do with my rejection of country growing up; it just sounded like sappy, overproduced crap when compared to hip-hop and grunge.

Unlike today, however, middle of the road country music in the 1970s faced a formidable outlaw insurgency by artists influenced by the counter-culture, and who declared independence from Nashville's rules and strictures. This is the kind of country music that made me love a genre I used to loathe. Here are the five best (or at least my favorite) outlaw country songs of the 1970s.

1. Waylon Jennings, "Are You Sure Hank Done It This Way?"

Jennings hit an amazing hot streak in the 1970s after getting artistic control over his records. More than any other outlaw artist, he managed to transcend the "pop" versus "tradition" conflict in country music. On this song he is traditional in that he name-checks Hank Williams and implicitly criticizes modern Nashville. On the other hand, this driving song is built around a electric rock guitar and has few of country music's traditional markers. There's no steel guitar or choruses, just a pulsating, relentless beat. This song is ultimate proof that country music can draw from its reservoirs of tradition and still incorporate modern sounds without being derivative. Whenever I hear this song, I hear the sound of of what might have been.

2. Kris Kristofferson, "Sunday Morning Coming Down"

While Johnny Cash sang the definitive version of this song (as I highlighted in a recent post), it was written by Kristofferson. A student of literature with an obvious Bob Dylan influence, Kristofferson revolutionized country songwriting by giving it poetry and lyrical sophistication. There is no other song that can describe so vividly how a bad hangover can make you feel absolute despair and Weltschmertz.

3. Willie Nelson, "Whiskey River"

Speaking of drinking, "Whiskey River" is probably the best of a venerable country song genre: the "I am drinking (and failing) to forget her" song. It comes off of Nelson's killer Shotgun Willie album, which is loaded with great songs like the title track and "Sad Songs and Waltzes." The grooving bass and driving rhythm guitar would sound at home on a soul record, another example of outlaw country's admirable ability to improve traditional sounds by borrowing from other genres.

4. Waylon Jennings, "Old Five and Dimers Like Me"

This comes off the Honky Tonk Heroes album, perhaps the best of the whole outlaw genre and also a showcase for songwriter Billy Joe Shaver. I've always liked to say that the older I get, the more I appreciate classic blues, R&B, and country, because these genres are music for adults with adult problems, like broken marriages, money problems, and getting old. This ballad really cuts deep, as it articulates the feeling I have now in my early middle age that if I was ever going to amount to anything, it would have happened by now. The way Waylon sings "An old five and dimer is all I really meant to be" with such pained resignation gets me every time.

5. Tompall Glaser, "Put Another Log on the Fire"

Here's a satirical song told from the point of view of an ogre, a la Randy Newman. The character is a chauvinist pig of the worst sort with a list of demands for his wife, but the last words are "put another log on the fire/ and tell me why you're leaving me." Women like Loretta Lynn had written about crummy husbands and male boorishness before, but this may be the first feminist country song sung by a man, and a great one at that.

Unlike today, however, middle of the road country music in the 1970s faced a formidable outlaw insurgency by artists influenced by the counter-culture, and who declared independence from Nashville's rules and strictures. This is the kind of country music that made me love a genre I used to loathe. Here are the five best (or at least my favorite) outlaw country songs of the 1970s.

1. Waylon Jennings, "Are You Sure Hank Done It This Way?"

Jennings hit an amazing hot streak in the 1970s after getting artistic control over his records. More than any other outlaw artist, he managed to transcend the "pop" versus "tradition" conflict in country music. On this song he is traditional in that he name-checks Hank Williams and implicitly criticizes modern Nashville. On the other hand, this driving song is built around a electric rock guitar and has few of country music's traditional markers. There's no steel guitar or choruses, just a pulsating, relentless beat. This song is ultimate proof that country music can draw from its reservoirs of tradition and still incorporate modern sounds without being derivative. Whenever I hear this song, I hear the sound of of what might have been.

2. Kris Kristofferson, "Sunday Morning Coming Down"

While Johnny Cash sang the definitive version of this song (as I highlighted in a recent post), it was written by Kristofferson. A student of literature with an obvious Bob Dylan influence, Kristofferson revolutionized country songwriting by giving it poetry and lyrical sophistication. There is no other song that can describe so vividly how a bad hangover can make you feel absolute despair and Weltschmertz.

3. Willie Nelson, "Whiskey River"

Speaking of drinking, "Whiskey River" is probably the best of a venerable country song genre: the "I am drinking (and failing) to forget her" song. It comes off of Nelson's killer Shotgun Willie album, which is loaded with great songs like the title track and "Sad Songs and Waltzes." The grooving bass and driving rhythm guitar would sound at home on a soul record, another example of outlaw country's admirable ability to improve traditional sounds by borrowing from other genres.

4. Waylon Jennings, "Old Five and Dimers Like Me"

This comes off the Honky Tonk Heroes album, perhaps the best of the whole outlaw genre and also a showcase for songwriter Billy Joe Shaver. I've always liked to say that the older I get, the more I appreciate classic blues, R&B, and country, because these genres are music for adults with adult problems, like broken marriages, money problems, and getting old. This ballad really cuts deep, as it articulates the feeling I have now in my early middle age that if I was ever going to amount to anything, it would have happened by now. The way Waylon sings "An old five and dimer is all I really meant to be" with such pained resignation gets me every time.

5. Tompall Glaser, "Put Another Log on the Fire"

Here's a satirical song told from the point of view of an ogre, a la Randy Newman. The character is a chauvinist pig of the worst sort with a list of demands for his wife, but the last words are "put another log on the fire/ and tell me why you're leaving me." Women like Loretta Lynn had written about crummy husbands and male boorishness before, but this may be the first feminist country song sung by a man, and a great one at that.

Thursday, August 8, 2013

Track of the Week: Bunny Sigler, "Theme for Five Fingers of Death"

I was listening to a great show on WFMU yesterday while driving the car around New Jersey doing my pre-trip errands. The DJ was spinning some seriously nasty 70s funk deep cuts, which I recalled later in the day seeing Robin Thicke perform on Colbert. Thicke is alright, but he is doing a decent version of 70s Philly soul, when I'd rather listen to the real thing.

A few years back I picked up a great compilation of lesser known songs put out by the Philadelphia International label, best known for a smooth, sophisticated and polished sound exemplified by McFadden and Whitehead's "Ain't No Stopping Us Now," The O'Jays' "Love Train" and Lou Rawls' "You'll Never Find a Love Like Mine." When I started spinning the compilation, called Conquer the World, I was taken aback by the hard-edged funk mixed in with the string-laden ballads.

My favorite funky cut would have to be Bunny Sigler's "Theme For Five Fingers of Death," which shows us that Carl Douglas' over-played "Kung Fu Fighting" was not the only martial arts-themed 70s funk song, and hardly the best. It just comes bursting out of the speakers like a flying side-kick, and never lets up. A gravelly voice challenges Shaft and Superfly to a fight, before admonishing his apprentice not use his powers for personal glory, which his student affirms at the end. There's not much here in terms of lyrics, apart from keyups, but I'd rather hear the liquid electro-funking organ do the talking instead. Hearing this song makes me want to put my old tae kwon do uniform on and break some boards, too bad I last wore it at age 12.

Friday, August 2, 2013

Of "Meritocracy" and Academic Lifeboaters

Recently on the blog Pan Kisses Kafka, Rebecca Schuman fired off what I think is her best essay yet on the degradations of the academic humanities. This has prompted the usual chorus of Mr. Blifil-type priggish jerks who croak "meritocracy" in protest. To them anyone who complains about academia's inequalities is just a bitter failure who didn't get a job because they just weren't good enough. Needless to say, such words put me in a blinding rage.

These folks usually ignore larger social and economic forces when making such accusations. They conveniently forget 2008's financial Gotterdammerung, when the already paltry academic job market in the humanities went into full-on starvation mode for years. New jobs stopped opening, and other listings got axed completely. Until very recently, professional organizations like the AHA had been acting as if this wasn't happening. I think the change came once the anointed scions of the profession's big name profs couldn't get jobs.

Many of the meritocracy chorus are the type baby boomers who inspired the deathless Old Academe Stanley meme. Like the rest of their peers in other walks of life, boomer academics have been savoring their lucrative late-earning years, and even the most supposedly Leftist among them often seem wholly ignorant of the ways in which their champagne and caviar lifestyle is supported by the ramen noodle penury of adjuncts, visitors, and graduate teaching assistants. Worse yet, they refuse to recognize that if they had to apply today for the job they got forty years ago, there is no way a great many of them would get hired.

But I'll save my boomer rant until later, since that will require more reservoirs of outrage than even I can muster. No, I'd rather go after a contingent of scholars who I like to call the "life boaters." These are junior scholars who don't bother thinking about the naked exploitation of a system where adjuncts are paid as little as $1,700 a course, and do just as good of a job (or better) as they do. In their minds, they won, they're on the lifeboat, and fuck all those other people drowning around them.

Some lifeboaters are just willfully ignorant; they got a good job straight out of graduate school, and came out of their apprenticeship into a comfortable journeyman position, just like their advisor said they would. These lifeboaters merely annoy me, at least until they take their position for granted. I have witnessed, and heard anecdotally, of many lifeboaters who have decided to become driftwood even before their tenure, wholly oblivious to the fact that there are hungry academic gutter snipes with publications on their CVs and fire in their bellies ready to take their place.

Other lifeboaters, usually from more elite institutions, have the attitude of nineteenth century Social Darwinians: since they are doing well, it must be purely based on their own efforts. They look at those around them drowning under ridiculous teaching burdens, a total lack of scholarly support, and a tight job market and see failures and losers who just didn't try hard enough to pull themselves up by their bootstraps. They refuse to acknowledge that blind luck and their advisors' connections/reputation have a lot to do with success on the job market. I myself partially got hired to my old t-t job because my research topic was inordinately interesting to someone on the hiring committee. If not for that coincidence, I probably wouldn't have gotten the job.

This is not to say that people with tenure-track jobs haven't earned their positions, they have. It's that there are a lot of people out there just as hard-working, intelligent, and qualified who deserve far better than they have received. Plenty of academics seem to recognize this dynamic in wider society, and realize that privilege and luck have a lot to do with one's social class, not just "personal responsibility." Yet when they see these class dyanamics happening in their own fucking backyards, they prefer to think of their place on the hierarchy, and the lowly ones of many of their peers, to be completely natural and just.

As much as the lifeboaters drive me into a state of blind fury, I know that they are soon to be reaping a brutal harvest. The current system of temporary labor is eroding tenure and eating away at professorial privilege; soon only the Ivy elites will have that great big tenured position in the sky. The reserve army of the unemployed has been and will continue to be used a cudgel against tenured and tenure track faculty: do as you're told, or we can replace with someone who'll do the job for less money and do less complaining. Or better yet, via MOOCs and other schemes, professorial work will be automated and only the superstars will lecture, most of the folks on the tenure-track crying "meritocracy" will find themselves demoted into glorified teaching assistants. That's not something I want to see, but the lifeboaters who have passively accepted or actively defended the adjunct system of cheap labor and hierarchy are complicit in this dark future. Enjoy your comeuppance, meritocrats!

These folks usually ignore larger social and economic forces when making such accusations. They conveniently forget 2008's financial Gotterdammerung, when the already paltry academic job market in the humanities went into full-on starvation mode for years. New jobs stopped opening, and other listings got axed completely. Until very recently, professional organizations like the AHA had been acting as if this wasn't happening. I think the change came once the anointed scions of the profession's big name profs couldn't get jobs.

Many of the meritocracy chorus are the type baby boomers who inspired the deathless Old Academe Stanley meme. Like the rest of their peers in other walks of life, boomer academics have been savoring their lucrative late-earning years, and even the most supposedly Leftist among them often seem wholly ignorant of the ways in which their champagne and caviar lifestyle is supported by the ramen noodle penury of adjuncts, visitors, and graduate teaching assistants. Worse yet, they refuse to recognize that if they had to apply today for the job they got forty years ago, there is no way a great many of them would get hired.

But I'll save my boomer rant until later, since that will require more reservoirs of outrage than even I can muster. No, I'd rather go after a contingent of scholars who I like to call the "life boaters." These are junior scholars who don't bother thinking about the naked exploitation of a system where adjuncts are paid as little as $1,700 a course, and do just as good of a job (or better) as they do. In their minds, they won, they're on the lifeboat, and fuck all those other people drowning around them.

Some lifeboaters are just willfully ignorant; they got a good job straight out of graduate school, and came out of their apprenticeship into a comfortable journeyman position, just like their advisor said they would. These lifeboaters merely annoy me, at least until they take their position for granted. I have witnessed, and heard anecdotally, of many lifeboaters who have decided to become driftwood even before their tenure, wholly oblivious to the fact that there are hungry academic gutter snipes with publications on their CVs and fire in their bellies ready to take their place.

Other lifeboaters, usually from more elite institutions, have the attitude of nineteenth century Social Darwinians: since they are doing well, it must be purely based on their own efforts. They look at those around them drowning under ridiculous teaching burdens, a total lack of scholarly support, and a tight job market and see failures and losers who just didn't try hard enough to pull themselves up by their bootstraps. They refuse to acknowledge that blind luck and their advisors' connections/reputation have a lot to do with success on the job market. I myself partially got hired to my old t-t job because my research topic was inordinately interesting to someone on the hiring committee. If not for that coincidence, I probably wouldn't have gotten the job.

This is not to say that people with tenure-track jobs haven't earned their positions, they have. It's that there are a lot of people out there just as hard-working, intelligent, and qualified who deserve far better than they have received. Plenty of academics seem to recognize this dynamic in wider society, and realize that privilege and luck have a lot to do with one's social class, not just "personal responsibility." Yet when they see these class dyanamics happening in their own fucking backyards, they prefer to think of their place on the hierarchy, and the lowly ones of many of their peers, to be completely natural and just.

As much as the lifeboaters drive me into a state of blind fury, I know that they are soon to be reaping a brutal harvest. The current system of temporary labor is eroding tenure and eating away at professorial privilege; soon only the Ivy elites will have that great big tenured position in the sky. The reserve army of the unemployed has been and will continue to be used a cudgel against tenured and tenure track faculty: do as you're told, or we can replace with someone who'll do the job for less money and do less complaining. Or better yet, via MOOCs and other schemes, professorial work will be automated and only the superstars will lecture, most of the folks on the tenure-track crying "meritocracy" will find themselves demoted into glorified teaching assistants. That's not something I want to see, but the lifeboaters who have passively accepted or actively defended the adjunct system of cheap labor and hierarchy are complicit in this dark future. Enjoy your comeuppance, meritocrats!