Now that summer's here, I have way too much time to think about the esoteric elements of pop music. I find it funny that certain techniques and bells and whistles get used to the point of parody by artists and producers in certain era. For example, after SNL's famous "more cowbell" sketch, I noticed the ubiquity of cowbell all over classic hard rock, from Mountain's "Mississippi Queen" to Grand Funk Railroad's "We're an American Band." More recently, auto-tuning has become ubiquitous, and credit/blame has to be given to Cher's "Believe." The charts haven't been the same since.

Here's an odd thing I noticed awhile back while listening to classic rock radio in my car: arena rock bands of the late seventies-early eighties period seemed partial to using keyboard triplets in their songs. It kinda works, in that it gives the fairly boring arrangements a sense of urgency. This style was mastered first by the pros in Toto via their hit "Hold the Line," which got a lot of play on the Godfather's pizza jukebox in my hometown back in the day. A year later Jefferson Starship blatantly borrowed Toto's approach with the slightly more up-tempoed "Jane." (This song is used to great effect in the opening credits sequence of Wet Hot American Summer.) Last but not least, Bon Jovi began their regretably long career with the triplet driven "Runaway." Weird, huh?

Pop music of the same era also relied very heavily on saxophone riffs solos. I think it probably started with Gerry Rafferty's "Baker Street" and confirmed itself with Supertramp's "Logical Song" in the late 1970s. In these songs, which are about the pain of growing old and dying dreams, the saxophone expresses a kind of emotional anguish. Accordingly, when George Michael in his Wham! days wanted to show his more sensitive, less cavorting around in short shorts side with "Careless Whisper," he put a big honkin' sax riff on the track. This device was a tad overused, and with time became less effective. For example, the sax solo on Tina Turner's "We Don't Need Another Hero" is pretty bitchin', but moreso as a musical, rather than emotional moment. Of course, sometimes the intended effect was just to add something punchy and distinctive, like the sax solo on Huey Lewis and the News' "Heart of Rock and Roll," The Waitresses' "I Know What Boys Like" or Billy Joel's "You May Be Right."

I am not sure what replaced the sax solo after the mid-80s, but likely candidates are squeely guitar, overly big-sounding snare drums, or synthesized horn sections. As cheesy as they were, I have to say I wish they would have stuck with piano triplets ans sax solos instead.

Wednesday, July 31, 2013

Piano Triplets and Sax Solos

Monday, July 29, 2013

Top Five Things I Miss About Smoking

I started smoking at the age of 22, and despite quitting for long stretches (sometimes for a year at a time), never gave the habit up completely until about three years ago or so. I was thinking about this today while reading an article in the Sunday Review of the New York Times of a genre I despise: the "neuroscience explains everything" article. It is authored by two scientists who claim they have discovered why certain people still smoke: they are willpower deficient weaklings who are incapable of delaying gratification. Of course, as a historian I scratch my head and recall that many, many more people smoked sixty years ago, and I doubt that the percentage of such folks was so much higher back then. The authors of the article also seem totally oblivious to the relationship that smokers have with their habit. When I smoked I knew it was bad for my health, but I also tended to smoke the most at times when my will to live was at its weakest. I didn't do it because my willpower was weak, I did it because it felt great and I wasn't thinking that living to be 90 was a worthwhile goal.

Since then, my will to live has grown. (Funny how that happened after I left academia.) I had cut down my intake to about a pack a week, which left me in the clear as far as lung cancer went, but still meant my heart could explode in an untimely fashion. That thought got me to finally kick the habit for good. Unlike other non-smokers, however, I am not some kind of born-again fanatic when it comes to nicotine. I do not evangelize smokers and urge them to quite, mostly because I know that approach doesn't work. And, truth be told, there are good things about smoking I miss. Here'a list of the top five.

1. The buzz

Of course this is #1. Smoking feels good, dammit! Picture this, you wake up groggy and tired, not wanting to start your day, but while you're waiting for the coffee to brew, you light up a cig and wha-bam! you're feeling good. Drink that coffee while you smoke that cigarette, and the buzz washes over you like a warm wave. Having a mediocre beer? Well light up your smoke and sciddly diddly bop, your beer is supercharged! Tired after a long day? Shazzam! Nicotine gives you that nudge you need. The buzz doesn't outweigh its killer consequences, but all the PSAs in the world cannot change the fact that smoking feels pretty damn fine.

2. Instant comradeship

When I smoked, I easily made new friends in every corner of the world. There were people I didn't know who would freely give cigarettes to me, and others whom I would share with without giving it a second thought. I have struck up innumerable interesting conversations with fascinating strangers simply by standing outside smoking. (In fact, that's how I met my wife!) We didn't need small talk or ice breakers, we were smokers, part of a scorned yet tight-knit fraternity. I miss being in that club sometimes.

3. Looking cool

Sucking cancerous smoke into your lungs and blowing it out shouldn't look cool, but it does. It's the reason why smoking stayed prominent in films well after it went down in the real world, despite the protestations of anti-smoking groups. The golden age of Hollywood is one big advertisement for tobacco. Could you imagine Humphrey Bogart or Marlene Dietrich without a lit cig? No way! I have always been a terminally uncool dude, but when I was about 20, and took a drag from a friend's smoke for a laugh and a cute girl I liked said that it suited me, well, some ideas got in my head. It was not often that cute girls complimented me, and smoking gave this small-town nerd some needed edge.

4. Killing boredom

These days the smart phone is the boredom killer par excellence. Stuck in line at the grocery store or waiting for the next subway train? Just start scrolling and texting. Back in olden times when this convenience did not exist, smoking was a pleasurable way to kill time. Waiting for the bus, as I often had to do when I was a grad student, was the perfect time to light one up and experience a little bit of happiness. I'd still take that over my Twitter feed if not for the health effects.

5. Feeling subversive

As I mentioned earlier, I spent my youth as a nerdy outcast in rural Nebraska. I was thus attracted to outsider culture, reading the Beats and Hunter S. Thompson, but too chickenshit and goody goody to drop acid or go hitchhiking or anything like that. When I started smoking, however, I found out I was challenging the system without even trying. This was in the late 90s, remember, right around the time of the huge tobacco settlement with the US government, which consequently unleashed a torrent of anti-smoking propaganda. I suddenly had what I'd always wanted: a totem to mark myself as a subversive outside of the confines of square society, man. I loved the fact that I could piss off prissy non-smokers, like the obnoxious person who passed me by one day in downtown Atlanta, making exaggerated, passive aggressive coughing noises. Here she was, in this horribly polluted city smelling like a Chevy tailpipe, singling me out because I was taking a drag on a Camel. I felt like I was screaming out a manifesto without saying a word: That's right, asshole, I smoke! Get used to it! Tobacco saved the Virginia colony and built America! And I didn't have to overcome my fear of social confrontation.

I am very glad I quit smoking, especially now that I am a parent. However, there are a few things about smoking I will defend. Its use spiked in the mid-20th century, a time of war, economic collapse, death, and general uncertainty. Why care about your long term health when you won't have money to grow old with, or the atom bomb will likely blow you to smithereens? In a world like that, if you don't live in the moment, you're a sucker. Smoking is the ultimate way to live in the moment, the future be damned, and with things going pretty rotten these days, I wonder if smoking isn't ripe for a comeback.

Saturday, July 27, 2013

Track of the Week: Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers, "Even the Losers"

I've always thought Tom Petty has never ascended to his rightful place in the rock pantheon, and that the Heartbreakers have been a criminally underrated band. Much of this probably has to do with timing. Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers' first album came out in 1976, at the point that 60s-originated classic rock music had shifted into terminal decline. The Stones, Beatles, Kinks and Who had been swept aside in favor of Journey, Kansas, Boston, REO Speedwagon, and Styx. Metal and punk soon pushed things into radical new directions that made the old school, blues-based rock look pretty stale.

Petty was a throwback, trading Byrds-inspired chiming guitar licks with the great Mike Campbell, and backed by a band of Southern rockers who remembered rock's R&B foundations. The Heartbreakers did have some of the intensity and edge that drove punk, but no one was mistaking them for the Ramones. Even though they were successful, they really didn't fit into any of the established categories of the time.

Listening to that music today, it's hard to think of anything from the late 1970s and early 1980s that matched Tom Petty's output. Even the non-hits still shine. "Even the Losers," from the 1979 blockbuster Damn theTorpedoes is not one of Petty's best known tracks, but is one of my favorites. There's the usual bright, jangly guitars and Benmont Tench warm organ accompaniment, but also some of Petty's better lyrics. The catchphrase on the chorus, "even the losers get lucky sometimes" has always stuck with me, especially now after I survived years of rejection in the academic world only to find unexpected contentment. In the verses there's some great imagery, like "two cars parked on the overpass/ rocks in the water like broken glass/ I shoulda known right then it was too good to last/ God it's such a drag when you live in the past." When he sings "even the losers get lucky sometimes" on the chorus, it's not triumphal (despite the soaring guitars), but a hopeful prayer that things somehow will work out the next time around.

There's no virtuosic playing, no distorted guitar, no screaming vocals, no anything reminiscent of prog, punk, or heavy metal. The music serves the song, and isn't there to posture or beat the listener into submission. It's a kind of smart minimalism that makes Petty great, but often leaves him forgotten when lists of the "greats" are composed. He's still high up in this loser's book, though.

Thursday, July 25, 2013

On Being Post Post-Academic

With the collapse of the humanities and simultaneous gutting of the academic profession, there are plenty of folks out there who have left the groves of academe for greener pastures. Many identify themselves explicitly as "post-academic," a term which I guess could maybe be applied to me as well. Post-academics are both outside academia, but also engaged in a critical critique of it. The more militant types take a John Brown approach, hoping to free those entrapped in a system that has failed them.

These days I don't really think I'm post-academic, I'm more post post-academic. Why? Because I no longer give a flying fuck about the academic profession. I. Do. Not. Care. I do not see its fate in any way to be connected to my own. Post-academics are still invested in reforming the system or at least trying to change it. I have withdrawn my investment, except for the fervent hope that my friends still immeshed in it will be protected, advance up the ladder, or find a better life.

For the longest time I wondered how I could leave something I had devoted my entire adult life to. Turns out, it was pretty damn easy. What I discovered was that for once in my life, my gut instincts were actually correct. When I started graduate school, many things I saw really bugged me about the academic profession. Many scholars wrote indecipherable prose intended to prove a didactic political point, and yet were deemed successful, even demigods. Others professed a support for the toiling masses, but were more than happy to reap the benefits of cheap grad student labor. Uninspiring scholarship on "trendy" topics got rewarded much more than much more impressive research on non-trendy topics. Some profs at my grad school, whose salaries were taxpayer supported, disdained teaching undergraduates as beneath them, and thought any professor who did care to be suspect and inadequate as a scholar. The whole enterprise stank of bourgeois snobbery, hypocrisy, and privilege, even though I had and still retain a great deal of respect and admiration for many of the professors in my graduate department. When I started going to big conferences, I had a hard time seeing myself as a member of the professors' club.

Worse, once I left grad school and became a "visiting" professor and later an assistant prof, I noticed the most damning thing of all: nobody was satisfied. I found the place where I "visited" to be a wonderfully livable city and the school to be comfortable enough, but the tenured and tenure-track professors were often miserable, thinking they ought to be in a trendier location, or employed at a more prestigious university. At conferences I often heard much the same from people I knew who actually had R-1 jobs in major cities. They still weren't satisfied with their positions, and I began to wonder if anyone in this self-hating club ever reached a stage of contentment.

Over the years I found ways to ignore my nagging doubts and socialized myself into academic culture. While a student enjoying my immersion in the study of history, I did not give much thought to what came after. I was lucky enough to be surrounded by a bunch of fantastic people, and was happier than I had ever been in my life, despite the poverty, anxiety, and labor demanded by grad school life. Once I was out and trying to claw my way out of contingent labor into a tenure-track gig, and then to fight my way out of my tenure-track job to be closer to my wife, the immense effort of six years on the job market blinded me to the fact that I was sacrificing myself for a profession I wasn't suited for, and which had rewarded my years of toil with rejection and anguish.

Leaving academia initially made me feel like a failure and a reject, but the tables have turned. I reject academia, because it has failed. It's fucked up and wrong, not me. Rather than define myself as "post-academic" and tilt my lance at the windmills of higher ed, I'd rather just forget about the whole tawdry, overrated, hypocritical, awful mess of a profession that it is, even if my posts on academia tend to get the most hits. That chapter of my life is over, and good riddance to it.

These days I don't really think I'm post-academic, I'm more post post-academic. Why? Because I no longer give a flying fuck about the academic profession. I. Do. Not. Care. I do not see its fate in any way to be connected to my own. Post-academics are still invested in reforming the system or at least trying to change it. I have withdrawn my investment, except for the fervent hope that my friends still immeshed in it will be protected, advance up the ladder, or find a better life.

For the longest time I wondered how I could leave something I had devoted my entire adult life to. Turns out, it was pretty damn easy. What I discovered was that for once in my life, my gut instincts were actually correct. When I started graduate school, many things I saw really bugged me about the academic profession. Many scholars wrote indecipherable prose intended to prove a didactic political point, and yet were deemed successful, even demigods. Others professed a support for the toiling masses, but were more than happy to reap the benefits of cheap grad student labor. Uninspiring scholarship on "trendy" topics got rewarded much more than much more impressive research on non-trendy topics. Some profs at my grad school, whose salaries were taxpayer supported, disdained teaching undergraduates as beneath them, and thought any professor who did care to be suspect and inadequate as a scholar. The whole enterprise stank of bourgeois snobbery, hypocrisy, and privilege, even though I had and still retain a great deal of respect and admiration for many of the professors in my graduate department. When I started going to big conferences, I had a hard time seeing myself as a member of the professors' club.

Worse, once I left grad school and became a "visiting" professor and later an assistant prof, I noticed the most damning thing of all: nobody was satisfied. I found the place where I "visited" to be a wonderfully livable city and the school to be comfortable enough, but the tenured and tenure-track professors were often miserable, thinking they ought to be in a trendier location, or employed at a more prestigious university. At conferences I often heard much the same from people I knew who actually had R-1 jobs in major cities. They still weren't satisfied with their positions, and I began to wonder if anyone in this self-hating club ever reached a stage of contentment.

Over the years I found ways to ignore my nagging doubts and socialized myself into academic culture. While a student enjoying my immersion in the study of history, I did not give much thought to what came after. I was lucky enough to be surrounded by a bunch of fantastic people, and was happier than I had ever been in my life, despite the poverty, anxiety, and labor demanded by grad school life. Once I was out and trying to claw my way out of contingent labor into a tenure-track gig, and then to fight my way out of my tenure-track job to be closer to my wife, the immense effort of six years on the job market blinded me to the fact that I was sacrificing myself for a profession I wasn't suited for, and which had rewarded my years of toil with rejection and anguish.

Leaving academia initially made me feel like a failure and a reject, but the tables have turned. I reject academia, because it has failed. It's fucked up and wrong, not me. Rather than define myself as "post-academic" and tilt my lance at the windmills of higher ed, I'd rather just forget about the whole tawdry, overrated, hypocritical, awful mess of a profession that it is, even if my posts on academia tend to get the most hits. That chapter of my life is over, and good riddance to it.

Labels:

academia,

leaving academia,

post academia

Monday, July 22, 2013

Good Albums, Bad Covers

For the past five years or so, record collecting has become my new, sometimes expensive hobby. At least this weekend I went trolling for vinyl at a flea market in South Jersey, where I got three classic records for a mere four bucks. One great advantage of LPs is their large size, which many have used over the years as a canvas for some truly wonderful art. Of course, there are also some famously awful album covers out there. The most famous tend not to be classic albums, but there are in fact some great albums with equally bad covers. Here are, to me, the albums with the biggest contrasts between the greatness in the grooves and the crapitude of the cover.

Rolling Stones, Let It Bleed

This is a timeless nugget from the Stones' glory years, containing such memorable tunes as "Gimme Shelter," "Midnight Rambler,"and "You Can't Always Get What You Want," along with two of my all-time fave Stones deep cuts: "You Got the Silver" and "Monkey Man." The former's got a rare Keith vocal and sublime slide guitar, the latter a searing turn by Jagger and the latter some of sickest open-tuning this side of Robert Johnson. However, the cover just sucks. There are a lot of jumbled elements to it, and none of them interesting. Who in the hell wants to picture the Greatest Rock and Roll Band in the World as birthday cake topping?

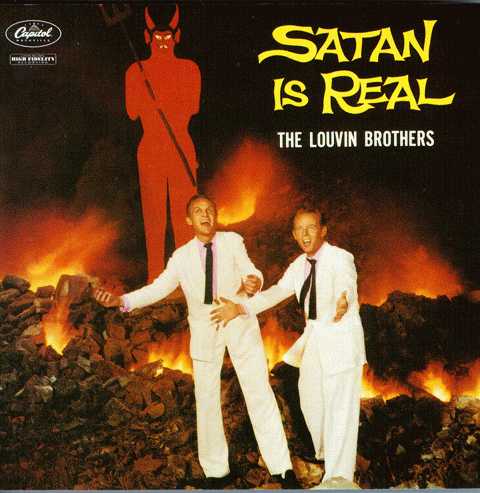

Louvin Brothers, Satan is Real

On this record the Louvin Brothers reach country gospel perfection with eerie close harmonies that can't be beat. If they see fit to give me a church funeral, I'd certainly want "I'm Ready to Go Home" to accompany my casket out the door. However, this cover features a cardboard cut-out of Satan that's more silly than scary. At least it's good for a laugh.

Beatles, Revolver

Revolver is the best Beatles record, hands down. It's full of amazing experimentation like "Tomorrow Never Knows," sitting side by side with beautiful pop songs like "Good Day Sunshine." It manages to combine all the great elements that band could muster, but without the pretentiousness of Sgt. Pepper or clunker songs like "Ob-La-Di" or "Maxwell's Silver Hammer" to prevent perfection. I have to honestly say I took awhile to pick up this album because I thought the cover was so awful. The rendering of the Beatles by Klaus Voorman look like a piece of teenage fan art drawn in a math class notebook, and doesn't really resemble the Beatles that much.

Steely Dan, Can't Buy a Thrill

The Dan's debut is a real pleasure and full of standards like "Dirty Work" and "Reeling in the Years," but the cover looks like a bad acid trip barfed all over it.

Led Zeppelin IV

Such a great record, arguably Zep's best, and certainly it's most well-known. The cover is just wretched, though. For a record full of the most mystically grandiose rock music ever recorded, including one inspired by The Lord of the Rings ("The Battle of Evermore"), they chose a peeling wall with an old painting of a man gathering sticks on it. It's too clumsy to be a knowing contrast to the music, and certainly not worthy to grace such an epic album.

Beach Boys, Pet Sounds

Here's another fantastic record with a sterling reputation that I held off on getting because I could not believe that any record with a cover this ridiculous could possibly be all that great. Not only is the concept just silly and undignified, the photo looks hastily chosen. Carl Wilson's face is caught in a moment of contorted disgust, and Mike Love has his eyes closed. Brian Wilson must still be peeved that his magnum opus, containing such triumphs as "Wouldn't It Be Nice" and "Caroline No," among others, is associated with a trip to the petting zoo.

Rolling Stones, Let It Bleed

This is a timeless nugget from the Stones' glory years, containing such memorable tunes as "Gimme Shelter," "Midnight Rambler,"and "You Can't Always Get What You Want," along with two of my all-time fave Stones deep cuts: "You Got the Silver" and "Monkey Man." The former's got a rare Keith vocal and sublime slide guitar, the latter a searing turn by Jagger and the latter some of sickest open-tuning this side of Robert Johnson. However, the cover just sucks. There are a lot of jumbled elements to it, and none of them interesting. Who in the hell wants to picture the Greatest Rock and Roll Band in the World as birthday cake topping?

Louvin Brothers, Satan is Real

On this record the Louvin Brothers reach country gospel perfection with eerie close harmonies that can't be beat. If they see fit to give me a church funeral, I'd certainly want "I'm Ready to Go Home" to accompany my casket out the door. However, this cover features a cardboard cut-out of Satan that's more silly than scary. At least it's good for a laugh.

Beatles, Revolver

Revolver is the best Beatles record, hands down. It's full of amazing experimentation like "Tomorrow Never Knows," sitting side by side with beautiful pop songs like "Good Day Sunshine." It manages to combine all the great elements that band could muster, but without the pretentiousness of Sgt. Pepper or clunker songs like "Ob-La-Di" or "Maxwell's Silver Hammer" to prevent perfection. I have to honestly say I took awhile to pick up this album because I thought the cover was so awful. The rendering of the Beatles by Klaus Voorman look like a piece of teenage fan art drawn in a math class notebook, and doesn't really resemble the Beatles that much.

Steely Dan, Can't Buy a Thrill

The Dan's debut is a real pleasure and full of standards like "Dirty Work" and "Reeling in the Years," but the cover looks like a bad acid trip barfed all over it.

Led Zeppelin IV

Such a great record, arguably Zep's best, and certainly it's most well-known. The cover is just wretched, though. For a record full of the most mystically grandiose rock music ever recorded, including one inspired by The Lord of the Rings ("The Battle of Evermore"), they chose a peeling wall with an old painting of a man gathering sticks on it. It's too clumsy to be a knowing contrast to the music, and certainly not worthy to grace such an epic album.

Beach Boys, Pet Sounds

Here's another fantastic record with a sterling reputation that I held off on getting because I could not believe that any record with a cover this ridiculous could possibly be all that great. Not only is the concept just silly and undignified, the photo looks hastily chosen. Carl Wilson's face is caught in a moment of contorted disgust, and Mike Love has his eyes closed. Brian Wilson must still be peeved that his magnum opus, containing such triumphs as "Wouldn't It Be Nice" and "Caroline No," among others, is associated with a trip to the petting zoo.

Labels:

bad album covers,

music,

popular culture

Saturday, July 20, 2013

Track of the Week: Waylon Jennings, "Lonesome, On'ry, and Mean"

Whenever I go back to Nebraska, I am faced with the very difficult experience of feeling like a stranger in my own hometown. Going back reminds me that I am a very different person from the one I used to be. I am fine with having changed, but it makes me feel alien and estranged from my family and all kinds of other people who were like family to me growing up. We live in different worlds, but they're still good people, even if we have a hard time relating to each other nowadays.

Of all the classic country I've listened to this week, "Lonesome, On'ry and Mean" has stuck out the most, maybe because it echoes some of my feelings. It's the first track on a killer album of the same name, the first album where Waylon Jennings was allowed complete artistic control. It's not hard to see the lyrics about getting on a bus and getting the hell out of town and "doing things my way" as a reference to his estrangement from the country music establishment in Nashville. The basic tone of the song is "get me outta this fuckin' place before I go nuts." That's pretty much how I felt back when I was 18 and went off to college. That day was like an emancipation for me, a liberation from the bullying, close-mindedness, philistinism, and exclusion that I endured from a very young age. For the longest time since that glorious day I'd felt less like I had rejected my hometown than I had fled as some sort of a refugee from a place that had already rejected me a long time ago.

These days I look back a little differently. The kids my age treated me like dogshit, but I had two very loving parents who sacrificed a lot for me. I didn't have many friends, but my parents' friends and their kids were like a second family, and we had a lot of great times together. "Lonesome, On'ry and Mean" thus embodies my binary relationship to my hometown. The song's subject matter reminds me of how happy I was to get the hell out, but it's outlaw country perfection helps me remember the good things I had that I can still take with me, like an appreciation for Waylon Jennings and badass country music.

Labels:

music,

nebraska,

track of the week,

Waylon Jennings

Friday, July 19, 2013

Dear Hollywood: Bring the Joy and Fun Back to Summer Movie Season

I have been an avid movie-goer for pretty much my entire life. Two weeks ago, when my wife had to work and my in-laws had a day with the kids, I chose to go see a documentary about the cult rock band Big Star at the Independent Film Center. There's no where else I would have rather been on a hot summer afternoon with some time to kill. I grew up going to movies all the time, mostly because it was one of the few legal activities for teenagers available in my sleepy rural hometown. Most of the time I just went to theater and saw whatever struck my fancy, which is how I ended up viewing fare such as Karate Kid III, Crocodile Dundee II, Far and Away, Johnny Be Good, and any number of entries in the Police Academy saga.

Of course, I also saw some great summer movies, and I still have fond memories not just of the movies themselves, but of the time I spent in the theater with friends, having a shared experience enjoying a great movie. Films like Ghostbusters, Return of the Jedi, Back to the Future, and Goonies were well-made, funny, and yes, joyous things to behold. Nothing in my movie-going life will probably ever top seeing Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade on the evening of the last day of school in the seventh grade. I remember leaving the theater with a friend, breathing the warm early summer air and feeling nothing but hope and possibility.

That feeling has become much more elusive at the summer multiplex, and I don't think it's just because I'm older now. Up until very recently, I would take in plenty of summer flicks. My wife and I share this passion, and two summers ago during a canoeing and camping trip on the Niobrara River, we left the campsite for a night to go to the local town to see a movie. During the last two summers taking care of two infants has meant seeing many fewer summer movies, but my wife and I just don't seem to mind now. The summer movies that we are being offered just don't appeal to us; we go out of our way and beg for grandparent day care to see arty stuff like Before Midnight, not World War Z.

A lot of this is a matter of quality, since critics I trust haven't really been excited by much either. However, I think it goes beyond quality. The joy and fun that made movies like Ghostbusters and Back to the Future so enjoyable just aren't there anymore. I blame a lot of this on the current Hollywood adaptations of comic book superheroes, who, by their very nature, are difficult to relate to as human beings. They also tend to be over-serious and not fun, at least in terms of how Hollywood portrays them. I would expect this from Batman, of course, but the new Superman was (according to my sources) mirthless and even a shade vicious. A movie like Back to the Future gets you to root for the characters, or at least to be amused by the wild-eyed zaniness of Doc Brown and the oddball nerdiness of George McFly. The original Sam Raimi Spiderman had some of these qualities, but Peter Parker still acted like an annoying emo teenager.

In the last five summers or so I can only think of a small number of summer movies that gave me a glimpse of that old joy. One was WALL-E, which is less a children's flick than a brilliant social critique. Another Pixar flick, Toy Story 3, absolutely ripped my heart out. Apart from Pixar, I really loved Super 8, much more so than director JJ Abrams' more financially successful reboot of the Star Trek franchise. Super 8 betrayed a great deal of love and heart; Abrams has famously said that he had little love of Star Trek, and it shows. Super 8, however, was a throwback to the summer fare of yore, when the audience could get behind regular people thrust into extraordinary circumstances, rather than brooding crime fighters with super powers/super gadgets. Best of all, it was original. So much these days is warmed over or rehashed, and just too damn familiar. Franchises like Spider Man have had two incarnations since 2000, and Hollywood still shamelessly mines old material like Get Smart and even freaking board games, a la Battleship. Since 1989, there have been seven Batman movies. I like Batman as much as the next person, but there is such a thing as too much of a good thing. The studios think there are audiences in familiarity, but the wells are dangerously close to being sucked dry.

So Hollywood execs, pay heed and listen to me. Bring back humor to your blockbusters, real humor, not Jar Jar Binks forced humor. Take a cue instead from the hilarious interplay of Harrison Ford and Sean Connery in The Last Crusade. Cast comedic actors (like Bill Murray and Christopher Lloyd back in the day) in comedic roles, not just hunks of man meat like Channing Tatum. Start greenlighting more original ideas instead of franchises; the love of the film-makers will be on the screen, and if the film is good, the audiences will definitely respond. Go back to having real people in blockbusters. Close Encounters of the Third Kind, for example, works so well because we can empathize with Richard Dreyfus' character. You might choose not to listen to me, but do so at your own peril. Television has finally become a medium for mature, artistic expression. You still have the ability to one-up television by making great spectacles, but if those spectacles keep getting more distant from something real, true, and joyous and become rote CGI-fests, you will find fewer and fewer people willing to trek to the multiplex. You've been warned.

Wednesday, July 17, 2013

Classic Albums: Tom Waits, Heartattack and Vine

I came to Tom Waits late in life, but like Paul on the road to Damascus, the scales fell from my eyes and I preach Waits' gospel every chance I get. A friend in college was a Waits disciple too, and always used to play his stuff for me without winning me over. His music seemed willfully obtuse, his voice abrasive, and none of it really fit with other artists I liked. My girlfriend in grad school tried to win my soul for the bard of the gutter, and I didn't crack until she loaned me a copy of Heartattack and Vine.

For some reason, it just clicked with me, which is funny considering that is not one of his more highly rated records. Allmusic only gives it three stars out of five, the second lowest score for any of his albums, and much lower than those that come right after. Robert Christgau's B grade review is chock full of faint praise. Released in 1980, it is a transitional album marking Waits' shift from his jazzbo lounge singer persona of the 1970s to his avant garde wildman stage that began in earnest with 1983's revolutionary Swordfishtrombones. Up until this point Waits' jazz piano laid the foundation, afterward it would be unorthodox percussion. On Heartattack and Vine, it's the blues. I think people don't like this record for the same reason I didn't like Waits for so long: it doesn't fit pre-existing categories. Maybe that's why it was the one to hook me, it had a quality I lacking in the other stuff I'd heard.

The bluesy nature of the proceedings is apparent when the title track kicks of the record in raucous fashion. A cutting, drunkenly lumbering guitar staggers into the room, soon accompanied by one of Waits' signature growls. He uses this to best effect on one of his all time best lines "There ain't no devil, just God when he's drunk." When I heard this song, his sandpaper and Marlboros voice suddenly made sense to me the way that Howlin' Wolf's similarly unorthodox vocal stylings always had. Waits' singing is really better suited to blues-based material, and here his voice finally gets the right platform.

Other songs on the record mine the depths of the blues, especially the caustic "Downtown" and perverted "Mr. Siegal." However, it's a couple of weepy ballads that make this album so great. The first is "Jersey Girl," a song that has a lot of meaning for me. I was listening to Waits a lot around the time I met the Jersey girl who would later be my wife. When Waits says "Nothing else matters in this whole wide world, when you're in love with a Jersey girl" my heart swells. Beyond my own subjective biases, it really is a fetching ballad, and expresses, without being maudlin, the insane magic of falling in love. When my wife and I slow-danced to this at our wedding it was probably the happiest I felt that day.

The other ballad is the monumental "On the Nickel," whose title refers to 5th Street in LA (hence "nickel.") This is skid row, and Waits is singing a lullaby to the men who live there. The accompanying strings are lush, like something off of a Disney soundtrack, his voice whisperingly tender at the start. Halfway through it gets low and fearsomely gutteral, as if he is channeling the pain and broken hopes of the men for whom he sings. By the end if you are not moved, you have no heart.

None of the other songs can match "Heartattack and Vine," "Jersey Girl," or "On the Nickel," but a record with three awe-inspiring songs counts as a classic in my book. It might not fit the image Waits fans or critics have of him, which is all the more reason to admire it as one of the most confounding works of a charmingly confounding artist.

Monday, July 15, 2013

White Racial Apathy Kills

The other day the ever-wise Chauncey DeVega wrote something that articulated well an inchoate idea I've been pondering for a long time but unable to fully express:

"I offer a painful truth: indifference is worse than anger or hate. The vast majority of white folks who enjoy racial privilege--as well as men, heterosexuals, the rich and upper class, the "able bodied", and others that benefit from unearned advantages in American society--do not care or think very much about those who are in the out-group. Why? Because the luxury to be indifferent and ignorant about the life experience of the Other is the very product of privilege. "

I'd like to piggyback on that statement, especially on how we ought to question understandings of racism where whites are constantly, actively keeping hierarchy in place and perpetuating a racist society. There are certainly plenty of folks like that, of course. A man like George Zimmerman, who actively went after a black teenager for the crime of walking home from a convenience store where he "didn't belong" and killed him after provoking an altercation certainly fits that bill.

The travesty of justice in the Trayvon Martin case clearly shows that despite what people like John Roberts think, overt racism is alive and well in America today. However, in our "color blind" and "post racial" society, the most powerful means through which oppression is maintained are much less overt and much more insidious. Most racism these days is entirely unconscious, and one of the worst manifestations of it is through something I'd like to call "white racial apathy." By this I mean the luxury of white people mentioned by Chauncey DeVega to not give a damn about the problems of people of color, and to refuse to understand their perspective.

This apathy has been evident from the get go among whites who profess ignorance as to how this case could be "about race," and while not defending Zimmerman, certainly feel that too much is being made out of the whole affair. These same folks also tend not to understand all the calls to end practices like stop and frisk. They've never had to be humiliated by the police or been considered "suspicious" based on who they are, and furthermore, don't really care to understand the point of view of those affected by the policy. This apathy means that the broken judicial system that exonerated Zimmerman and has set up a school-to-jail pipeline in many communities in this country will continue to operate without reform. Millions suffer, but they are primary people of color, and the predominating attitude of apathy regarding people of other races in white America means that nothing will change.

There are a couple of examples of this apathy that hit home for me, and which are literally killing people. The first is here in my adopted state of New Jersey, where some crimes matter, and some don't. There's been a lot of hubub recently about a home invasion in the affluent suburb of Millburn, where a burglar physically assaulted a mother after breaking into her home in broad daylight. The fact that his attack was caught on video has made this case much more sensational, as has the fact that the attacker was an African American man, and the victim a white woman. This attack has received a great deal of attention here, and each development has been discussed in the bars, diners and living rooms across New Jersey.

That attention is rather interesting compared to the yawning silence outside of Newark about the rise in murders in Brick City since governor Christie cut back state aid, necessitating police lay-offs. These murders have been increasingly brazen, such as the shooting of a bodega owner in a robbery in January, a clerk at a convenience store in March, the tragic death of 19 year old (with an infant child) while working behind the counter at his family's deli last September and perhaps most shocking, the death of a mother of four this May at the hands of a stray bullet. Of course, there are many factors beyond police layoffs to blame, but the cutbacks have most certainly meant that there people who are dead today who would still be alive had there been more police on the streets. Governor Christie himself does not seem to give a damn, nor do many people outside of Newark, who see this city as a "no-go" zone best avoided and forgotten about. Instead of being outraged at the horrible deaths of people in their own state which may well have been preventable, suburban white New Jersey simply does not give a shit about the fates of black and brown people in the cities.

Back in my home state of Nebraska this white apathy is killing in a different way. A small hamlet called Whiteclay on the South Dakota border has liquor stores that sell 4.9 million cans of beer a year. That sounds impossible, but this town takes advantage of the fact that it is very close to the Pine Ridge reservation, where alcohol is banned. This has been a boon for unscrupulous merchants, who charge inflated prices while knowingly making their riches off of the misery of Native Americans, while simultaneously undercutting the tribe's attempts to solve the problem of rampant alcoholism and its horrific effects on the community. The local white population doesn't seem to have a problem with this state of affairs, though. Recently Sioux leaders went to talk with governor Dave Heineman about the issue, and he evidently told them that since the alcohol sales were legal, it was "their problem." That is the voice of white racial apathy at its most genuine, using the law as a dodge and excuse and not even bothering to understand the enormity of the situation. While governor Heineman has probably already forgotten about this meeting, the bodies will keep piling up. That's usually the consequence of white racial apathy.

"I offer a painful truth: indifference is worse than anger or hate. The vast majority of white folks who enjoy racial privilege--as well as men, heterosexuals, the rich and upper class, the "able bodied", and others that benefit from unearned advantages in American society--do not care or think very much about those who are in the out-group. Why? Because the luxury to be indifferent and ignorant about the life experience of the Other is the very product of privilege. "

I'd like to piggyback on that statement, especially on how we ought to question understandings of racism where whites are constantly, actively keeping hierarchy in place and perpetuating a racist society. There are certainly plenty of folks like that, of course. A man like George Zimmerman, who actively went after a black teenager for the crime of walking home from a convenience store where he "didn't belong" and killed him after provoking an altercation certainly fits that bill.

The travesty of justice in the Trayvon Martin case clearly shows that despite what people like John Roberts think, overt racism is alive and well in America today. However, in our "color blind" and "post racial" society, the most powerful means through which oppression is maintained are much less overt and much more insidious. Most racism these days is entirely unconscious, and one of the worst manifestations of it is through something I'd like to call "white racial apathy." By this I mean the luxury of white people mentioned by Chauncey DeVega to not give a damn about the problems of people of color, and to refuse to understand their perspective.

This apathy has been evident from the get go among whites who profess ignorance as to how this case could be "about race," and while not defending Zimmerman, certainly feel that too much is being made out of the whole affair. These same folks also tend not to understand all the calls to end practices like stop and frisk. They've never had to be humiliated by the police or been considered "suspicious" based on who they are, and furthermore, don't really care to understand the point of view of those affected by the policy. This apathy means that the broken judicial system that exonerated Zimmerman and has set up a school-to-jail pipeline in many communities in this country will continue to operate without reform. Millions suffer, but they are primary people of color, and the predominating attitude of apathy regarding people of other races in white America means that nothing will change.

There are a couple of examples of this apathy that hit home for me, and which are literally killing people. The first is here in my adopted state of New Jersey, where some crimes matter, and some don't. There's been a lot of hubub recently about a home invasion in the affluent suburb of Millburn, where a burglar physically assaulted a mother after breaking into her home in broad daylight. The fact that his attack was caught on video has made this case much more sensational, as has the fact that the attacker was an African American man, and the victim a white woman. This attack has received a great deal of attention here, and each development has been discussed in the bars, diners and living rooms across New Jersey.

That attention is rather interesting compared to the yawning silence outside of Newark about the rise in murders in Brick City since governor Christie cut back state aid, necessitating police lay-offs. These murders have been increasingly brazen, such as the shooting of a bodega owner in a robbery in January, a clerk at a convenience store in March, the tragic death of 19 year old (with an infant child) while working behind the counter at his family's deli last September and perhaps most shocking, the death of a mother of four this May at the hands of a stray bullet. Of course, there are many factors beyond police layoffs to blame, but the cutbacks have most certainly meant that there people who are dead today who would still be alive had there been more police on the streets. Governor Christie himself does not seem to give a damn, nor do many people outside of Newark, who see this city as a "no-go" zone best avoided and forgotten about. Instead of being outraged at the horrible deaths of people in their own state which may well have been preventable, suburban white New Jersey simply does not give a shit about the fates of black and brown people in the cities.

Back in my home state of Nebraska this white apathy is killing in a different way. A small hamlet called Whiteclay on the South Dakota border has liquor stores that sell 4.9 million cans of beer a year. That sounds impossible, but this town takes advantage of the fact that it is very close to the Pine Ridge reservation, where alcohol is banned. This has been a boon for unscrupulous merchants, who charge inflated prices while knowingly making their riches off of the misery of Native Americans, while simultaneously undercutting the tribe's attempts to solve the problem of rampant alcoholism and its horrific effects on the community. The local white population doesn't seem to have a problem with this state of affairs, though. Recently Sioux leaders went to talk with governor Dave Heineman about the issue, and he evidently told them that since the alcohol sales were legal, it was "their problem." That is the voice of white racial apathy at its most genuine, using the law as a dodge and excuse and not even bothering to understand the enormity of the situation. While governor Heineman has probably already forgotten about this meeting, the bodies will keep piling up. That's usually the consequence of white racial apathy.

Saturday, July 13, 2013

Track of the Week: Kenny Rogers, "The Gambler"

My two daughters, born a year ago this week, have been making the transition from sweet, cheerful babies into terroristic toddlers. Bedtime used to be easy. I would put them in their cribs, read to them for a bit, and then leave some soothing music playing. Nowadays they fight sleep with all their might, and I've found that singing to them is one of the few things that gets them to calm down. The other night, faced with this task, I wracked my brains for a song to sing to them, and the words of "The Gambler" by Kenny Rogers started pouring out of my mouth.

That was hardly a mistake, since there are few songs I associate more with my own early childhood. Back then my parents owned only about six albums (all on cassette), and the one played most often was The Gambler. (John Denver, The Carpenters, Tony Orlando, Mel Tillis, and Lawrence Welk were some of the other choices.) This song always takes me back to the earliest memories that I have.

It's a song that has resonated with a lot of people besides me. How many other country ditties have spawned a made for TV movie and three sequels? (I once saw them all for sale together as a DVD box set called "The Gambler Saga.") Perhaps it's because it's one of the few radio hits to dispense valuable life advice. You may laugh, but my leaving academia was both a time to know when to fold them, and when to run. Tucking my daughters in every night reminds me I did a helluva lot more than break even.

Labels:

Kenny Rogers,

leaving academia,

music,

track of the week

Thursday, July 11, 2013

An Attempt to Explain Louie Gohmert By a Former Resident of His Congressional District

With Michele Bachmann leaving Congress, no one seems more primed to take her crown as the most demented member of Congress than Texas Republican representative Louie Gohmert. Unlike the rest of America, I knew of him well before his idiotic remarks and harebrained theories catapulted him into the public eye. I had the misfortune to live in his district in East Texas for three years, and have come to the conclusion that he cannot be explained without understanding the electorate that puts him in Congress.

I am of the opinion that jerko politicians often represent the very worst of the regions they hail from. For example, Chris Christie's loud-mouthed uncouth bullying exemplifies a certain mean streak here in the Garden State. In his two-facedness, arrogance, and fast-talking torrents of bullshit, Anthony Weiner embodies the worst of New York City. The aforementioned Michele Bachmann is a more photogenic version of the crazy-eyed fanatical Midwestern churchladies of my youth. Rahm Emmanuel is the quintessential sharp-elbowed Chicago asshole on the make. Much the same could be said of Gohmert, who combines the worst of East Texas in one person.

As much as I disliked my time in East Texas, I can readily acknowledge the good things about the state. Hell, Austin and Houston are two of my favorite cities; too bad I was living in a reactionary rural 'burg. Wendy Davis' filibuster represented a lot of what I liked about Texas, mainly the large number of tough people who are willing to fight hard against long odds for progressive causes on hostile ground. You will not find folks on the political left more clear-eyed and brave than in Texas; Molly Ivins and Ann Richards are probably the two best known examples of the type.

That said, a disproportionate number of Texans, especially behind the pine cone curtain in East Texas, are absolutely vile in their political, religious, and social outlooks, and not afraid to let other people know. One church in Nacogdoches actually has its white supremacist interpretation of the Bible posted prominently posted on its website. Of course, plenty of churches implicitly hold such beliefs, but the culture of the area is so messed up that people feel free to say it openly. The same town where the church is located only has a population of 30,000, but hosted a Tea Party rally in 2009 that numbered in the thousands. Believe it or not, it's a college town, and probably the most liberal in the whole Congressional district, if by liberal you mean slightly to the left of George Wallace.

The place is just generally retrograde. In the biggest city in the district, Tyler, you can't by booze, which reflects the cultural hegemony of evangelical fundamentalism. Tyler still has a high school named after Robert E Lee. Despite being a relatively small city, Glenn Beck was able to speak there and draw a huge, supportive crowd. The same venue, the Oil Palace, also hosted large gatherings for Sarah Palin and Sean Hannity. At the Beck event, a different Texas representative, Leo Berman, proclaimed "Obama is God's punishment on us." If thousands in a small community will turn out and enthusiastically support dopes like this, is it any surprise that they would elect a complete dimwit like Gohmert?

And Tyler and Nacogdoches are sophisticated compared the more rural environs of East Texas, where the Klan is still active. For years, police in Tehana routinely pulled over drivers for the crime of being black, and even shook them down for money. Most horribly, Jasper was the site of the infamous dragging death of James Byrd.

In this place so full of overt racism, Christian dominionism, and general oppression those who are critical are completely ostracized. They have so little power that Gohmert has been able to run unopposed on multiple occasions. There are plenty of good people in this area who I had the pleasure to know, but they are outnumbered, outgunned, and constantly face severe ostracism and hostility from the squareheads who surround them. There are some folks in the middle, too, but they just end up voting for whoever the Republicans put on the ballot, since they're just going with the cultural flow. I've escaped living there, but I feel horribly for the large percentage of people whose interests are the polar opposite of the man who supposedly "represents" them.

In a democracy, elected officials reflect their electorate, and Louie Gohmert is no exception.

As much as I disliked my time in East Texas, I can readily acknowledge the good things about the state. Hell, Austin and Houston are two of my favorite cities; too bad I was living in a reactionary rural 'burg. Wendy Davis' filibuster represented a lot of what I liked about Texas, mainly the large number of tough people who are willing to fight hard against long odds for progressive causes on hostile ground. You will not find folks on the political left more clear-eyed and brave than in Texas; Molly Ivins and Ann Richards are probably the two best known examples of the type.

That said, a disproportionate number of Texans, especially behind the pine cone curtain in East Texas, are absolutely vile in their political, religious, and social outlooks, and not afraid to let other people know. One church in Nacogdoches actually has its white supremacist interpretation of the Bible posted prominently posted on its website. Of course, plenty of churches implicitly hold such beliefs, but the culture of the area is so messed up that people feel free to say it openly. The same town where the church is located only has a population of 30,000, but hosted a Tea Party rally in 2009 that numbered in the thousands. Believe it or not, it's a college town, and probably the most liberal in the whole Congressional district, if by liberal you mean slightly to the left of George Wallace.

The place is just generally retrograde. In the biggest city in the district, Tyler, you can't by booze, which reflects the cultural hegemony of evangelical fundamentalism. Tyler still has a high school named after Robert E Lee. Despite being a relatively small city, Glenn Beck was able to speak there and draw a huge, supportive crowd. The same venue, the Oil Palace, also hosted large gatherings for Sarah Palin and Sean Hannity. At the Beck event, a different Texas representative, Leo Berman, proclaimed "Obama is God's punishment on us." If thousands in a small community will turn out and enthusiastically support dopes like this, is it any surprise that they would elect a complete dimwit like Gohmert?

And Tyler and Nacogdoches are sophisticated compared the more rural environs of East Texas, where the Klan is still active. For years, police in Tehana routinely pulled over drivers for the crime of being black, and even shook them down for money. Most horribly, Jasper was the site of the infamous dragging death of James Byrd.

In this place so full of overt racism, Christian dominionism, and general oppression those who are critical are completely ostracized. They have so little power that Gohmert has been able to run unopposed on multiple occasions. There are plenty of good people in this area who I had the pleasure to know, but they are outnumbered, outgunned, and constantly face severe ostracism and hostility from the squareheads who surround them. There are some folks in the middle, too, but they just end up voting for whoever the Republicans put on the ballot, since they're just going with the cultural flow. I've escaped living there, but I feel horribly for the large percentage of people whose interests are the polar opposite of the man who supposedly "represents" them.

In a democracy, elected officials reflect their electorate, and Louie Gohmert is no exception.

Tuesday, July 9, 2013

The Benefits of Rooting For a Crummy Baseball Team

This has not been a good season for my Chicago White Sox, who have stumbled down into the cellar of the American League Central, the least fearsome division in baseball. A combination of an aging core and mediocre performances has them losing game after game in a seemingly unending parade of futility. This year I decided to take on the Mets as my other rooting interest, since I have decided to permanently settle in the tri-state area. They are a franchise in disarray with a batting order full of guys who should be playing in AAA ball, not in the majors.

I still watch my teams' games, despite the fact that I usually see them lose, often in excruciating fashion. The Mets lost a 19 inning game awhile back, and the White Sox just lost four in a row at home to the Cubs, giving Chicago bragging rights to the North Siders. My only consolation is that the Astros and Marlins are worse, so at least my teams won't be the absolute rock bottom in either of their respective leagues.

That's cold comfort, of course, but I've found there are some benefits to rooting for a bad baseball team. Paradoxically, it makes fandom less stressful. Last year, when the White Sox slowly deflated at the end of the season and fell out of the first place position they held since spring, each loss was a fresh dagger to the heart. Now when they blow a few games it's irritating but not stress-inducing. There's nothing worse than a pennant race for the cardiac health of a baseball fan, and with both of my teams already out of contention, this season will prove to at least be more heart healthy than the last.

The other major benefit to rooting for a bad team is less tangible, but very important. By yoking oneself to a gang of cellar dwellers, you get practice in learning how to lose. This is a crucial skill, because most people's lives have more losses than they do wins. Baseball gives particularly intense training, because unlike other sports, it happens every day during the season, and so like life, goes on without a break. Each day when you pull for the likes of the Mets or White Sox, you wake up knowing that it is very likely that at least one thing in your life won't go the way you want it to that day.

But that's life, isn't it? Every day has the potential to bring something new and crummy. An unexpected bill will come in the mail, a family member will get ill, you'll break a dish, the cat will puke on the floor, you'll get passed over for promotion and so on and so on until the day you die. In life, you have to relish in the small moments of relief, like the dollar bill found in the street, your subway train arriving ahead of schedule, hitting all of the green lights, your favorite song coming on the radio, and your shitty baseball team somehow winning against a better squad. That's life, too.

Sunday, July 7, 2013

A Thought On a Year of Fatherhood

A year ago this week my wife gave birth to two wonderful baby girls. I haven't been writing about fatherhood much on this blog because 1. Parenting blogging is notoriously awful, no matter how well-intentioned and 2. My kids don't need all kinds of stuff about them floating around in cyberspace that they can read later and resent me for.

However, there has been one thought on my mind the last few weeks that sums up how parenthood has changed my outlook. If possible, I have become more pessimistic about the direction the world and this country in particular is taking. I wonder whether the children of two teachers will have the financial resources and connections to compete in a world without a middle class.

Out of one of my speculative moods I hatched a sci-fi image of the future that I can't shake from my head. By the time folks my age are retiring, Social Security and Medicare will be in tatters (if there at all.) In my vision, the government will offer a large lump cash sum to the families of those people who decide to be euthanized at the age of 65, since they will save so much precious money for the system. Now that I am a parent, I actually think that if such a future exists, I would volunteer to be put to death like Sol at the end of Soylent Green, if it would mean that my children could live life with financial security.

I know that's a crazy thought, but I feel like I would do anything I could for my children, no matter what. That willingness to sacrifice everything for my kids pretty much embodies everything fatherhood has done to my attitude towards my life.

However, there has been one thought on my mind the last few weeks that sums up how parenthood has changed my outlook. If possible, I have become more pessimistic about the direction the world and this country in particular is taking. I wonder whether the children of two teachers will have the financial resources and connections to compete in a world without a middle class.

Out of one of my speculative moods I hatched a sci-fi image of the future that I can't shake from my head. By the time folks my age are retiring, Social Security and Medicare will be in tatters (if there at all.) In my vision, the government will offer a large lump cash sum to the families of those people who decide to be euthanized at the age of 65, since they will save so much precious money for the system. Now that I am a parent, I actually think that if such a future exists, I would volunteer to be put to death like Sol at the end of Soylent Green, if it would mean that my children could live life with financial security.

I know that's a crazy thought, but I feel like I would do anything I could for my children, no matter what. That willingness to sacrifice everything for my kids pretty much embodies everything fatherhood has done to my attitude towards my life.

Saturday, July 6, 2013

Track of the Week: Chris Bell, "I Am The Cosmos"

This week my wife was kind enough to give me a day off from parenting, which I spent bumming around Manhattan. As part of my day of fun in the city, I took in Big Star: Nothing Can Hurt Me, a documentary about Big Star, a band from the early 70s that made great music but never made it. Their first two records are two of the most perfect ever, as far as I'm concerned, but they didn't get proper distribution, and were out of step with the gargantuan hard riffs and boogie beats that dominated the rock charts at the time.

I've been a big fan of the group since the 90s, but never learned much about their history, which I knew involved a lot of frustration. The film filled me in, in a most heartbreaking way. It is painful to see people make something great and struggle so hard to make it happen, only to be met with rejection and failure. I see so many friends in the academic world doing so many great things without getting recognized that I guess Big Star's story hits me a little more personally than before.

I was most moved by the story of Chris Bell, the band's erstwhile founder, who left after the first album due to frustration with the lack of success and competition with band member Alex Chilton. Evidently the lack of recognition upset him so much that he destroyed master tapes of his recordings. He went on to Europe and tried to get a record deal in England -where Big Star had been better known- but to no avail. He searched a lot in these years, chemically and spiritually, before his untimely death at age 27 in a car accident. Before his death, Bell managed to go back into the studio, and cut a 45 single, "I Am the Cosmos."

It sounds like his work with Big Star, but with so much more pain and longing behind it. The first, immortal lines come out in a kind of mournful croak: "Every night I tell myself I am the cosmos/ I am the wind/ But that don't get you back again." The first line is not bravado, but a futile attempt to forget a lost love. There are so many songs about the longing of heartbreak, but this cuts to the marrow more than almost any other. The abject longing in his voice when Bell croons "I really want to see you again" over and over again tells the story. The bright guitars and off-kilter rhythms that accompany the song echo the singer's fervent desire to mask his pain and burning need. If you've ever loved someone who left you, but you couldn't forget, no matter how hard you tried, this is the song you need to hear.

Thursday, July 4, 2013

Memories of the 4th of July on the Plains

Growing up July 4th was always one of my favorite holidays, and for one very obvious reason: firecrackers. It's a scientific fact that little kids of all stripes just love to blow stuff up, and the Fourth let's them do it with full social approval. Until I was older, my hometown banned any fireworks bigger than sparklers and glow worms, which was a real drag.

That, of course, didn't stop the fun, it just meant that our patriotic blast-fests had to be held outside of city limits. Often we celebrated Independence Day as a family get together. If on my mom's side, we'd go to my grandparents' farm, where we could blow off whatever we wanted to our heart's content. If on my father's side, we went to my aunt and uncle's farm, and did much the same. Best of all, in the summer of 1984 on the way home from a family vacation to Kansas City, we stopped at a fireworks warehouse off of the interstate and bought a massive amount of bottle rockets. These classic firecrackers/roof fire waiting to happen have long been illegal in Nebraska, prompting its residents to cross the border into the Show Me State to pick up some contraband. My dad, who loved firecrackers, bought enough bottle rockets to last us into the early 1990s, probably well past the date they could have been safely used. The open space on my relatives' farms made them optimal bottle rocket launching sites. The occasional strays only ended up in my grandma's potato patch, rather than setting a neighbor's yard ablaze.

The farms were also great places for those dinky parachute bombs, and gave plenty of room for my cousins and I to chase the little piece of cardboard attached to a tissue parachute that seemed to get tangled in the cottonwood trees half the time. We also had strategic methods of deploying our fireworks based on the tenacity of Nebraska's insect population in the summer time. Come July mosquitos, grass hoppers, junebugs, crickets, locusts, lightning bugs and all other manner of six-legged critters swarm the countryside. This was especially important at my aunt and uncle's farm, which sat down in a creek bottom that was a veritable breeding ground of creepy crawlies. After our drive home from my aunt and uncle's house, the front grill of my family's van looked like a freak science experiment. To hold the insects at bay, my cousins and I judiciously created a perimeter using smoke bombs, which were harmless enough that our parents let us use them without supervision. They also wanted relief from these awful, dumbass june bugs that loved to fly straight into our foreheads out of either stupidity or spite.

While the smoke bombs and bottle rockets were a riot, my most cherished memories involve some quality time with my grandfather. He was a gruff, hard man who had endured an abusive father, Depression-era poverty, and the loss of one of his kidneys during World War II. If you happened to be sitting in his cigarette burn-holed recliner when he came into the room you'd better jump up and get out of the way. He was a huge man with knuckles like doorknobs that testified to a life spent working on the farm. Even in retirement he wore overalls and work boots every day except for Sunday, when he donned a severely out of date brown suit for going to church. As tough as he was, he really had a soft spot in his heart for his grandkids, and loved spending time with us, even if we didn't say a lot to each other. I still remember sitting with him on the back porch on the Fourth, with a big paper sack full of inch and a halfers. My grandpa would light one after the other, holding each in his hand just long enough that when he tossed it out of his hand, it would explode before hitting the ground. I liked just sitting there with him and watching, and each Fourth for the past sixteen years brings the sad thought that I'll never get to do that with him ever again.

That, of course, didn't stop the fun, it just meant that our patriotic blast-fests had to be held outside of city limits. Often we celebrated Independence Day as a family get together. If on my mom's side, we'd go to my grandparents' farm, where we could blow off whatever we wanted to our heart's content. If on my father's side, we went to my aunt and uncle's farm, and did much the same. Best of all, in the summer of 1984 on the way home from a family vacation to Kansas City, we stopped at a fireworks warehouse off of the interstate and bought a massive amount of bottle rockets. These classic firecrackers/roof fire waiting to happen have long been illegal in Nebraska, prompting its residents to cross the border into the Show Me State to pick up some contraband. My dad, who loved firecrackers, bought enough bottle rockets to last us into the early 1990s, probably well past the date they could have been safely used. The open space on my relatives' farms made them optimal bottle rocket launching sites. The occasional strays only ended up in my grandma's potato patch, rather than setting a neighbor's yard ablaze.

The farms were also great places for those dinky parachute bombs, and gave plenty of room for my cousins and I to chase the little piece of cardboard attached to a tissue parachute that seemed to get tangled in the cottonwood trees half the time. We also had strategic methods of deploying our fireworks based on the tenacity of Nebraska's insect population in the summer time. Come July mosquitos, grass hoppers, junebugs, crickets, locusts, lightning bugs and all other manner of six-legged critters swarm the countryside. This was especially important at my aunt and uncle's farm, which sat down in a creek bottom that was a veritable breeding ground of creepy crawlies. After our drive home from my aunt and uncle's house, the front grill of my family's van looked like a freak science experiment. To hold the insects at bay, my cousins and I judiciously created a perimeter using smoke bombs, which were harmless enough that our parents let us use them without supervision. They also wanted relief from these awful, dumbass june bugs that loved to fly straight into our foreheads out of either stupidity or spite.

While the smoke bombs and bottle rockets were a riot, my most cherished memories involve some quality time with my grandfather. He was a gruff, hard man who had endured an abusive father, Depression-era poverty, and the loss of one of his kidneys during World War II. If you happened to be sitting in his cigarette burn-holed recliner when he came into the room you'd better jump up and get out of the way. He was a huge man with knuckles like doorknobs that testified to a life spent working on the farm. Even in retirement he wore overalls and work boots every day except for Sunday, when he donned a severely out of date brown suit for going to church. As tough as he was, he really had a soft spot in his heart for his grandkids, and loved spending time with us, even if we didn't say a lot to each other. I still remember sitting with him on the back porch on the Fourth, with a big paper sack full of inch and a halfers. My grandpa would light one after the other, holding each in his hand just long enough that when he tossed it out of his hand, it would explode before hitting the ground. I liked just sitting there with him and watching, and each Fourth for the past sixteen years brings the sad thought that I'll never get to do that with him ever again.

Tuesday, July 2, 2013

My Post Academic Stress Disorder

I left academia -an assistant professorship, at that- for greener pastures two years ago. While I am much happier, validated, better paid, and respected in my current job teaching at an independent high school in NYC, my academic past keeps haunting me. For example, when my school got a new director this year I started having panic attacks before the first day of school, concerned that this new boss might end up being like my old department chair. (Luckily he's been great and supportive.) I am already worried, even after getting unprecedented levels of praise for my performance this year, that my students next year will hate me. As much as I like my colleagues, I am always on the lookout for the one who will try to shiv me. I am often afraid to ask for anything at work, because I am sure I will be told no, and that my even asking for things will put me on the shit list of the powers that be.

These are not rational feelings in any objective sense, but are a kind of mental defense mechanism that victims of trauma erect in order not to be hurt again. During my time in academia, I was in a constant state of fear and degradation. As a "visiting" assistant professor I had no voice or power in my job, and had to go through the metaphorical servants' entrance all the time. Many of my colleagues would not even talk to or make eye contact with me, including the ones who had published less in their whole careers than I had in two years as a VAP. When I was an assistant professor I was bullied and mobbed by colleagues who had originally been friendly to me, and one of them even circulated an email among colleagues making a sexually derogatory joke meant to demean me. My chair barged his way into my office in a snorting rage not long after I complained about having to teach most of my classes outside of my field and on short notice at times. (I was once switched to a new class I had never taught in a field I wasn't trained in a mere two weeks before the semester!) I tried to get other jobs, but with each year I got fewer interviews, even after publishing a third article in a top journal and securing a book contract.

Even though others have not experienced the level of bullying and intimidation I faced, plenty of people who have survived academia know the feeling of worthlessness that comes with the profession. It is a world where nothing is ever good enough, and if you are a junior scholar, you have no power or say in anything. If you are bold enough not to STFU about your condition, you will be attacked or fired. It is a constant state of fear, with the knowledge that the reserve army of the unemployed who can replace you grows larger every year. Administrators use this fact as a cudgel to bash their faculty into submission. Educators in higher ed and in K-12 have been facing a wall of social hatred and scapegoating so fierce that many teachers and profs are losing heart. The emergence of MOOCs and the infiltration of academia by corporate interests has many wondering whether they will ultimately be turned into interchangeable parts to be plugged in and used for cut-rate wages before being tossed on the refuse pile. Worst of all, when you bash your head against the wall in frustration over all of your blood, sweat and tears adding up to nothing, the powers that be and their smug toadies tell you the system is a meritocracy, and you have no one to blame for your horrible situation but yourself.

I am glad not to be in the academic world anymore, but the mental and spiritual scars are not going away anytime soon. They are fading a little, at least. I can only hope that the panic attacks, nagging doubts, and bouts of self-loathing that make up my post academic stress disorder get rarer and rarer.