A friend of mine once told me that a sign of growing up working class is a father who "washes up" when he gets home from work. Since class is just as much cultural as it is economic, that's always made sense to me. When I worked factory jobs during my college summers, I'd come home covered in grime; "showering" could not begin to describe what I had to do when I got off work.

My own father had his own steady post-work ritual built up over years of labor: he would get home, "wash up," change into his casual clothes, and then sit down in his recliner and read the evening edition of the local newspaper. (My hometown is so old fashioned that we still have an evening edition.) He always washed up in the spartan basement bathroom, which until insurance money paid for renovation after a flood when I was in high school, consisted of an exposed copper water pipe, toliet, and metal shower spigots and pipes naked without tile or fancy fixtures. I never used the shower without wearing flip-flops; the shower floor -really just cement with an industrial drain in the middle- was that dirty.

Around the time dad finished the paper after he had washed up, we'd eat supper as a family, and he would finally be ready to socialize. His need for about forty-five minutes of quiet solitude after getting home subtly let me know that his job took a lot out of him. My mother, on the other hand, always came home with an indignant story about a treacherous colleague, dumbass administrator, or disobedient student (she's a high school teacher). She ranted and raved at the indignities of her job, but her anger and frustration reflected a real commitment to her profession. As much as she complained, I knew she taught because that's what she loved to do. If there has ever been such a thing as a born teacher in this world, she's it. My father, on the other hand, seemed not to have any real connection to his work besides that of duty. The duty to work hard, to not let the company down, and most of all, the duty to support his family. Perhaps his stoic sacrifice, enacted each and every day for decades, was the reason why he was much more supportive of my decision to go to graduate school than my mother. He knew full well what it was like to spend a life's energies on something he didn't want to do, and the need to pursue a dream.

Although he worked at a factory for over forty years until his retirement last year, my father had been a manager in the office, rather than working on the floor, since before I was born. (He worked as a machinist while going to night school, and once he graduated the company promoted him.) Despite the nature of his work, my father's working class upbringing never left him. He very rarely wore a suit and tie to his job, usually a pair of cotton slacks and an open-collar patterned button-down shirt instead, both purchased at K-Mart. Like his plain clothes. washing up might have been a ritual he maintained out of the very powerful force of habit among stubborn small town Midwesterners.

Now that I work at a high school rather than a university my work day has become much more rigid and ritualized. One of the great perks of academia is flexibility. I worked over fifty hours a week as a college professor (just like I do now), but I had a lot of freedom over when I worked those hours. Some days I got up early, on others I woke and worked late. Nowadays I get up at 5:30 every morning, get dressed, walk the dog, eat breakfast, walk to Penn Station, catch the train to the city, take the subway, walk to work, do my job, take the subway, ride the train, walk home, and walk the dog. This week, perhaps out of some kind of intergenerational osmosis, I've started washing up after walking the dog. It's quite invigorating; like a lot of rituals, it marks the transition from one state of being into another.

I guess I understand why my dad kept doing it, even though he no longer had to clean the grit of the factory off of his body. I must say I also hope that some of my father's virtues rub off on me by imitating his rituals. (To a point, of course. I am just as likely as my wife to be the one making dinner.) The older I get, the more I realize how much bullshit he had to swallow and how many dreams he had to defer each day he did his job, a job that allowed me to have a much more comfortable upbringing than the one he'd had. That's a debt I can never even hope to repay; my only hope is to be able to sacrifice half as much for my own children someday.

Tuesday, February 28, 2012

Sunday, February 26, 2012

The Favorite Buzzwords and Phrases Used by Educational Administrators, and What They Really Mean

Back when I was still an academic, my wife and I noticed that administrators at all levels of education tended to fall back on a ready reserve of stock words and phrases. Like all experts, including those in the supposedly more rarified air of higher ed, they use jargoned language to boost their authority by implying that they know something that other people, usually the faculty, don't. One increasingly hears these terms in our increasingly fatuous public discourse on education, where, like a virus, words like "accountability" attack the listener's brain and render it paralyzed. Luckily, I currently teach at an institution that has eschewed most of this heinous bullshit. Here are a few of the key terms I have noticed, with their real meanings broken down as a public service.

Flexibility

This term is borrowed from the corporate world, where "flexibility" means "we want to hire temporary and "part-time" labor so that we can keep our employees low-paid and compliant." This same meaning can apply to the use of adjunct labor in academia, but usually when administrators say they want the faculty to be "flexible" they mean "shut up and do as you're told."

The research data shows/studies say

Whenever administrators try to push a new initiative that the faculty don't like (especially in terms of assessment and online courses) they will silence their opponents by saying, "there are studies that show that this really works." Keep in mind that they don't actually present this data, or go into any detail as to how it was compiled, or even offer their own reasoning. The "studies show" gambit basically boils down to "I can't actually offer a convincing argument for why we're making you do this, just do it because we said so."

Student/child-centered learning

I am all for "student centered learning" in the abstract. My current institution actually practices it, but many administrators who invoke it do so only to make themselves sound good. "Student centered learning" has become a well-worn cliche, and really another way of saying "do whatever makes the customers happy."

Transparency

Again, I'm all for transparency, but in my line of work "transparency" is a one-way mirror. When the higher ups tell the hoi polloi that they want transparency, they really mean "we're going to be looking over your shoulder no matter what you do."

Accountability

This word has gotten a lot of mileage recently, and has been used as a rallying cry for attacking teachers and knee-capping professors. Of course, it is faculty who are always held accountable (and mostly the vulnerable untenured variety), while administrators are never evaluated. As my wife likes to say, accountability really means "do our job so we don't have to." As for me, it also means "don't forget who's in charge."

Innovation

Administrators love to claim that they are going to bring innovation. They often fancy themselves to be innovative, creative minds who must move the lazy, hidebound faculty into action. The word innovation, however, ought to be taken with a grain of salt. I've read a lot about the shenanigans that led to the financial collapse, and bankers used to throw around the word innovation to describe extremely risky practices that exploited loopholes in regulation. Similarly, academic and school administrators call things of questionable value that benefit their CV "innovation." For instance, forcing the university to use an entirely new software program for its admissions and academic records when the old one is doing just fine is a common "innovation" that the "innovator" will put on his/her resume when looking for the next step up on the academic ladder.

Assessment

This one is so tricky and laden with landmines that I should devote a whole post to it. The new assessment regime in our universities, in all its bureaucratic insanity, is like Dickens' Circumlocution Office combined with something straight of Jonathan Swift with a dose of Orwell thrown in. Let me just say that the word "assessment" has become as amorphous in its meaning and application as academic terms like "modernity" and "transnational."

Any other terms worthy of being added to the list?

Flexibility

This term is borrowed from the corporate world, where "flexibility" means "we want to hire temporary and "part-time" labor so that we can keep our employees low-paid and compliant." This same meaning can apply to the use of adjunct labor in academia, but usually when administrators say they want the faculty to be "flexible" they mean "shut up and do as you're told."

The research data shows/studies say

Whenever administrators try to push a new initiative that the faculty don't like (especially in terms of assessment and online courses) they will silence their opponents by saying, "there are studies that show that this really works." Keep in mind that they don't actually present this data, or go into any detail as to how it was compiled, or even offer their own reasoning. The "studies show" gambit basically boils down to "I can't actually offer a convincing argument for why we're making you do this, just do it because we said so."

Student/child-centered learning

I am all for "student centered learning" in the abstract. My current institution actually practices it, but many administrators who invoke it do so only to make themselves sound good. "Student centered learning" has become a well-worn cliche, and really another way of saying "do whatever makes the customers happy."

Transparency

Again, I'm all for transparency, but in my line of work "transparency" is a one-way mirror. When the higher ups tell the hoi polloi that they want transparency, they really mean "we're going to be looking over your shoulder no matter what you do."

Accountability

This word has gotten a lot of mileage recently, and has been used as a rallying cry for attacking teachers and knee-capping professors. Of course, it is faculty who are always held accountable (and mostly the vulnerable untenured variety), while administrators are never evaluated. As my wife likes to say, accountability really means "do our job so we don't have to." As for me, it also means "don't forget who's in charge."

Innovation

Administrators love to claim that they are going to bring innovation. They often fancy themselves to be innovative, creative minds who must move the lazy, hidebound faculty into action. The word innovation, however, ought to be taken with a grain of salt. I've read a lot about the shenanigans that led to the financial collapse, and bankers used to throw around the word innovation to describe extremely risky practices that exploited loopholes in regulation. Similarly, academic and school administrators call things of questionable value that benefit their CV "innovation." For instance, forcing the university to use an entirely new software program for its admissions and academic records when the old one is doing just fine is a common "innovation" that the "innovator" will put on his/her resume when looking for the next step up on the academic ladder.

Assessment

This one is so tricky and laden with landmines that I should devote a whole post to it. The new assessment regime in our universities, in all its bureaucratic insanity, is like Dickens' Circumlocution Office combined with something straight of Jonathan Swift with a dose of Orwell thrown in. Let me just say that the word "assessment" has become as amorphous in its meaning and application as academic terms like "modernity" and "transnational."

Any other terms worthy of being added to the list?

Thursday, February 23, 2012

A Compendium of Baseball Books

When baseball season approaches, I like to pick up a good baseball to read. I bought this season's book all the way back at Christmastime, Lawrence Ritter's The Glory of Their Times. It's a legendary oral history compiled in the 1960s of recollections by old ballplayers from the dead ball era of the early twentieth century. The stories are fantastic, like Rube Marqaurd hopping trains to get from Cleveland to his minor league team in Iowa, and Nebraska native Sam Crawford going from town to town with his local team in a covered wagon. This got me thinking about my favorite baseball books, and since I know some of the long-time readers of this blog, like me, love both books and baseball, I thought I'd share my thoughts on a few.

Favorite Book by a player: Jim Bouton, Ball Four

You have to love a book that gets its author called into the commissioner's office, which is exactly what happened after pitcher Bouton's account of his 1969 season was published in 1970. At a time when few players or baseball journalists let the public know the reality of baseball life, Bouton gave a day to day warts and all testimony, discussing the womanizing of idols like Mickey Mantle and strong-arm tactics used by owners in contract negotiations in the days before free agency. The dailiness of the book is its greatest asset, since it is a running diary of the season, and it more than anything else out there gives the reader a window into what it's really like to do the job of a ball player.

Honorable mention: Doug Glanville, The Game From Where I Stand

For those wanting a more modern take on baseball life, this is the book to get. Glanville has a wonderful writing style and great wit, as his columns attest.

Favorite Book about a single team's season: Jeff Pearlman, The Bad Guys Won

In case you didn't know, the "bad guys" of the title refer to the 1986 Mets, perhaps the most interestingly dysfunctional squad since the "Bronx Zoo" Yankees of the 1970s. Pearlman describes that team's rocky road to victory in one of the most exciting World Series ever, vividly sketching the many characters, from Gary Carter (may he rest in peace) to Keith Hernandez to Daryl Strawberry. Here's a hint: the title's pretty accurate.

Favorite Book by an owner: Bill Veeck, Veeck As In Wreck

Not a lot of competition for this category, but this is as funny a baseball book as they come. The former owner of the Browns and White Sox skewers fuddy duddy owners and relates one hilarious story after another. The best is his account of the Eddie Gaedel game, when Veeck's team put a midget in to pinch hit in order to get a player on base.

Favorite Player Biography: Howard Bryant, Hank Aaron: The Last Hero

I usually do not like biographies. They tend to be too long, too detail-oriented, and overly exaggerate the importance of their subjects. While Bryant's book has some issues, he does a fantastic job of exploring Aaron's life, in particular the difficult racial dynamics he faced as a black ballplayer in the early post-Jackie Robinson years.

Favorite Book of Analysis: Bill James, The Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract

As true baseball fans know, James' use of complex statistics has completely revolutionized the way that the game is seen and players are judged. What is less known is that James is a witty, compelling writer who does a fantastic job of humanizing his formulas and explaining them to a math-phobic audience. For my money, this is James' magnum opus and a book that any serious student of the game should read.

Favorite Book by a Manager: Joe Torre and Tom Verducci, The Yankee Years

As much as I dislike the Yankees, I really admire Torre, and he manages to do the impossible: make me feel sympathy for George Steinbrenner. Sure, he comes off a wee bit tyrannical, but also interested in getting his team to win above all else, a quality many fans wished their teams' owners had. Torre also offers priceless observations on A-Rod's vanity and an apt explanation of the Yankee franchise's decline after the 2001 season.

Favorite Book about Baseball Cards: Josh Wilker, Cardboard Gods

Wilker weaves his life into aphoristic discussions of individual baseball cards, making connections between the players and his own fate. I think it's one of the most brilliant things I've read in recent years, especially in exploring the contours of sports fandom. If you haven't yet, check out Wilker's blog.

Favorite Book That Does Not Exist Yet, but Should: Roger Angell, Complete Baseball Writings

Angell has written on baseball for the New Yorker for decades in wonderfully crafted, evocative prose. I have read all of the various collections of his various writings on baseball for that publication, but I think the time has come to gather them together in a single volume. I can't think of another writer who is so consistently interesting in his observations on the game. If you have a subscription to the New Yorker, go into the online archive and enjoy some of his vintage baseball material.

Tuesday, February 21, 2012

The Persistence of Baseball

Until about four years ago or so, I was an extremely close follower of the sporting scene. I listened to the radio shows, watched the highlight reels, and was aware of all the ups, downs, and scandals, from professional golf to college football. My interest in athletics did not match any real talent on my part. During the same youthful years that I had a subscription to Sports Illustrated, diagrammed my own football plays, and collected baseball cards, I found myself picked last in gym class with depressing regularity. It did not matter that I could recite the winners of all of the Super Bowls or the full line-up of the 1927 Yankees. Perhaps my interest in sports saved me from being a complete and total misfit, I could still hold my own in a sports conversation with my peers. (This did not always get me respect, however. Back in 1991 there was a bullying jerk in my science class who claimed the Bills would wipe the floor with the Giants in the Super Bowl. I thought he was wrong and bet him two bucks. When I asked to collect the day after the game, he punched me in the stomach instead of paying up.)

Since I have passed the age of thirty, my priorities in sports, as in many things, have shifted. I rarely watch ESPN, check the college football polls, or even take the time to watch my once beloved Nebraska Cornhuskers when they have a game on TV. I certainly get a kick out of the occasional game, and I greatly enjoyed seeing my first NBA game in person two weeks ago, but I am not "up" on most of the doings in the world of sports. Only two things truly remain vital to me, World Cup soccer and baseball. The World Cup is easy to explain, since it is the most important single sporting event in the world, and combines nationalism, history, identity, and global talent in a way that nothing else can match. Baseball might be harder to explain, since it has earned a reputation for being "slow" and "old fashioned." Professional football has overtaken it as America's premier spectator sport. Of all the team sports, I could actually play basketball reasonably well, and my playing experience allows me to understand the game with real depth. In fact, I probably get more enjoyment out of a well-played basketball game than any other. Why is it, then, that when I hear that pitchers and catchers have reported to spring training this week, my soul is lifted and I feel as if all is right in the world again?

I have liked baseball for a long time, but it is only in the last five years or so that this particular emotion has bubbled up inside of me. I delight in much of the game, from a well-thrown curve to a bang-bang play at the plate. Then again, I still marvel at a tight spiral, a quick drive to the hoop, and a bicycle kick goal. Perhaps my emotional connection is because now that my youth has ended, I appreciate and am more aware of my own mortality. Baseball's season, unlike that of other sports, mimics the human life cycle. It begins in spring, when flowers bloom and trees bud, reaches its pinnacle in the summer sun, and comes to an end as the leaves fall and the grass turns brown. The coming of baseball is a reminder that I am still alive, and that after winter's cold and dark, spring will come. It's a rather comforting thought.

Baseball is also something that I have to link me with ancestors. Both of my grandfathers loved baseball, and regaled me with stories in my youth of the 1930s "Gashouse Gang" Cardinals. My Dad and I still cherish our memories of playing catch in the backyard. Sure, we also shot "horse" and played one-on-one, but my father had never done that with his father, and not at such a young age.

This speaks to baseball's sense of history, the same attribute that leads to charges that it is retrograde, stuck in the past, un-modern. As a historian who has never felt comfortable in his own time, even as a child, baseball's immersion in the past (much more so than other sports) makes me feel more comfortable. Baseball connects more to the past because the rules and players have changed less than in other sports. Think about basketball before and after the three point line, and the innumerable rules changes regarding the forward pass in the NFL. With baseball, you can compare players more readily across eras, (at least after 1947) in ways that are impossible in other sports.

I also relish baseball's dailiness. Unlike other sports, even basketball and hockey, with their 82 game seasons, baseball goes on every day for six months solid, except for the day before and the day after the All-Star Game. Each team plays six days a week, their players coming to work to do their jobs much like the rest of us. The older I get and more removed I am from youth's freedom, the more my life has become a daily affair. I must get up early, walk the dog, catch the train, and do my job, and do the same the next day. Now that I am removed from the ivory tower of academe, and must plug away like the rest of working stiffs of this country, I have an even greater appreciation of a ball player's job.

Most of all, baseball is just much more fun to experience in person than the other major sports. I have greatly enjoyed myself at baseball games that were far from close or exciting. It's one of the most relaxing things for me to take a seat with the emerald diamond laid out before me, the sun shining, pennants blowing in the breeze, a beer in hand and that wonderful low buzzing chatter of the ball park in my ears. I can think of few things I would rather do on a summer day. Those summer days in our short lives are precious and few, and my heart leaps with the knowledge that they are soon to come again.

Sunday, February 19, 2012

Academic-Themed TV Shows I'd Like to See

Academics rarely appear on television, apart from talking heads or the rare show like The Paper Chase. Our culture is so rife with insanity and foolishness that reality shows and sit coms should start taking the ivory tower as a subject. Here are a few ideas that I've had:

Undercover Dean

Each week a dean will have to go back to being a full time faculty member, and actually implement the nonsensical assesment regime that they crafted, and be forced to sit through the ten office hours they require of faculty.

The Job Candidate

Similar to The Bachelor, several grad students and adjuncts will compete for the favors of an academic search committee. The show will follow the candidates through each stage of the weeding out process and track the wreckage of broken dreams and stress-induced ulcers.

The Academic Apprentice

On this reality show, graduate students will compete to be chosen as their advisor's favorite. Brown-nosing, backstabbing, and theft of research projects will give this program the drama that most reality show producers salivate over.

Southern Exposure

Taking the only academic job available, a young scholar from the Northeast moves to a small Arkansas town full of quirky locals who would be a lot more likable if he could get past their myopic, narrow-minded, and outright bigoted outlook on life.

Law and Order: Academic Integrity

In this show a team of scholars works to crack the toughest plagiarism cases. Each episode ends with the satisfactory punishment of an insufferably entitled millennial, only after the protests of parents and administrators are overcome.

What Not to Wear: Academic Edition

This would just be like shooting ducks in a barrel, wouldn't it?

Survivor: AHA Edition

Watch as impoverished graduate students must find out how to scrape the money together to attend a conference held at an expensive hotel in a faraway city just so they can talk for twenty minutes with a bored search committee inside of a loud, featureless, and overcrowded ballroom with zero room for dignity.

Shit My Chair Says

The title pretty much explains it all.

Wednesday, February 15, 2012

My Top Five Favorite All-Time "Out of Nowhere" Athletes

In case you haven't been paying attention, New York Knicks point guard Jeremy Lin has been taking the sporting world by storm these past two weeks. It's not just that he has been a great player for the NBA team in America's biggest media market, it's also that like Victor Cruz of the football Giants, he's a great "out of nowhere" athlete. As the enduring popularity of films like The Natural attests, American sports fans love it when a player who has been little regarded or obscure suddenly comes from out of nowhere to dominate in the big time. It speaks to the fantasies of fans themselves, and the idea that a schlub like them could play with the big boys.

Of course, Lin is hardly the first athlete to go from being cut and scrambling to find a job to sudden greatness. Here's a top five list of my favorite of such stories. Notice that I said "favorite," not "best" or "most compelling." My judgements are entirely subjective.

5. Mark "the Bird" Fidrych

I was barely alive for The Bird's magic 1976 season, but it's something that captured my attention at a young age seeing clips of him on a baseball show (probably This Week in Baseball.) He was 21 year old rookie from small town New England who talked to the ball, insisted on shaking the hands of all his opponents after his starts, and managed to win nineteen games with a league-leading 2.34 ERA. He did all of this while radiating a kind of child-like joy to be playing in the major leagues. Sadly an arm injury shortened his career in an era when surgery for pitchers was much less developed. This turned him from a potential all-time great player into one of the game's more colorful and memorable footnotes, and a reminder of the cruelties of the baseball gods.

4. Timmy Smith

Another rookie, Smith barely carried the ball during the 1987 season for the Redskins, running for only 126 yards. However, when Washington played the Denver Broncos in the Super Bowl, Smith ran for a record 204 yards, much more than he had racked up through the entire season! He's pretty much forgotten today, but his out of nowhere accomplishment ought to be remembered.

3. Kurt Warner

I've got a soft spot for Warner, since he's a fellow Midwesterner. As the story goes, he was bagging groceries at a Hy-Vee in Iowa when he got the call up to the St. Louis Rams. Warner had played college ball for Northern Iowa (hardly a big-time program) and hadn't even started there until his senior year. After failing to make it with an NFL team, he played in the Arena League, then Europe. Finally getting his chance to play on the big stage in 1999, he turned in one of the greatest single season performances by a quarterback in NFL history, and won the Super Bowl in the bargain. People forget it now, but that year's Rams offense was something truly remarkable to behold, a quick-striking juggernaut that made fools out of the best defenses in the league, and helmed by a guy who had nearly as much experience saying "paper or plastic" as calling audibles. He went on to be one of the best quarterbacks in the history of the game.

2. Geoff Blum

As a White Sox fan, Blum is especially near and dear to my heart. He came so far out of nowhere that I was an even more rabid Sox back fan in 2005 and still had little clue who he was. That's what you expect from a guy nicknamed "Random Man." Blum is a classic good field-no hit utility infielder whose versatility, rather than his bat, has kept in the major leagues, bouncing around between six different teams. A career .250 hitter, Blum got the right hit at the right time in the 2005 World Series, lifting the White Sox over the Astros with an epic homer in the 14th inning of game three. It was his only at bat of the entire series, but boy did he make it count.

1. Buster Douglas

Growing up in the sports world of the 1980s, I thought of Mike Tyson not as a mere mortal human being, but a kind of fearsome demigod. He might be a figure of mirth or disgust today, but back then nobody dared laugh or sneer at Iron Mike. Tyson brought a scary intensity and absolutely devastating punches to ring, and his fists dispatched many worthy challengers, from Larry Holmes to Michael Spinks, in embarrassingly short order. Then, in early 1990, Tyson fought the little regarded Buster Douglas in Japan in a bout that most Vegas odds makers didn't bother taking bets on. Shocking the world, the virtually unknown Douglas knocked the champ out. If you look at the film clip, you can see the absolute punishment he dished out on the heretofore undefeated Tyson, who looks completely lost after hitting the canvas, looking for his mouthguard with a dazed expression. Douglas promptly got fat, got beat bad by Evander Holyfield, and then retired. Where do you go after you defeat a man who was supposed to be invincible? Much like Alexander the Great after his conquests, Douglas simply didn't have anything else to fight for that could top what he had just done, and that was his undoing.

Of course, Lin is hardly the first athlete to go from being cut and scrambling to find a job to sudden greatness. Here's a top five list of my favorite of such stories. Notice that I said "favorite," not "best" or "most compelling." My judgements are entirely subjective.

5. Mark "the Bird" Fidrych

I was barely alive for The Bird's magic 1976 season, but it's something that captured my attention at a young age seeing clips of him on a baseball show (probably This Week in Baseball.) He was 21 year old rookie from small town New England who talked to the ball, insisted on shaking the hands of all his opponents after his starts, and managed to win nineteen games with a league-leading 2.34 ERA. He did all of this while radiating a kind of child-like joy to be playing in the major leagues. Sadly an arm injury shortened his career in an era when surgery for pitchers was much less developed. This turned him from a potential all-time great player into one of the game's more colorful and memorable footnotes, and a reminder of the cruelties of the baseball gods.

4. Timmy Smith

Another rookie, Smith barely carried the ball during the 1987 season for the Redskins, running for only 126 yards. However, when Washington played the Denver Broncos in the Super Bowl, Smith ran for a record 204 yards, much more than he had racked up through the entire season! He's pretty much forgotten today, but his out of nowhere accomplishment ought to be remembered.

3. Kurt Warner

I've got a soft spot for Warner, since he's a fellow Midwesterner. As the story goes, he was bagging groceries at a Hy-Vee in Iowa when he got the call up to the St. Louis Rams. Warner had played college ball for Northern Iowa (hardly a big-time program) and hadn't even started there until his senior year. After failing to make it with an NFL team, he played in the Arena League, then Europe. Finally getting his chance to play on the big stage in 1999, he turned in one of the greatest single season performances by a quarterback in NFL history, and won the Super Bowl in the bargain. People forget it now, but that year's Rams offense was something truly remarkable to behold, a quick-striking juggernaut that made fools out of the best defenses in the league, and helmed by a guy who had nearly as much experience saying "paper or plastic" as calling audibles. He went on to be one of the best quarterbacks in the history of the game.

2. Geoff Blum

As a White Sox fan, Blum is especially near and dear to my heart. He came so far out of nowhere that I was an even more rabid Sox back fan in 2005 and still had little clue who he was. That's what you expect from a guy nicknamed "Random Man." Blum is a classic good field-no hit utility infielder whose versatility, rather than his bat, has kept in the major leagues, bouncing around between six different teams. A career .250 hitter, Blum got the right hit at the right time in the 2005 World Series, lifting the White Sox over the Astros with an epic homer in the 14th inning of game three. It was his only at bat of the entire series, but boy did he make it count.

1. Buster Douglas

Growing up in the sports world of the 1980s, I thought of Mike Tyson not as a mere mortal human being, but a kind of fearsome demigod. He might be a figure of mirth or disgust today, but back then nobody dared laugh or sneer at Iron Mike. Tyson brought a scary intensity and absolutely devastating punches to ring, and his fists dispatched many worthy challengers, from Larry Holmes to Michael Spinks, in embarrassingly short order. Then, in early 1990, Tyson fought the little regarded Buster Douglas in Japan in a bout that most Vegas odds makers didn't bother taking bets on. Shocking the world, the virtually unknown Douglas knocked the champ out. If you look at the film clip, you can see the absolute punishment he dished out on the heretofore undefeated Tyson, who looks completely lost after hitting the canvas, looking for his mouthguard with a dazed expression. Douglas promptly got fat, got beat bad by Evander Holyfield, and then retired. Where do you go after you defeat a man who was supposed to be invincible? Much like Alexander the Great after his conquests, Douglas simply didn't have anything else to fight for that could top what he had just done, and that was his undoing.

Monday, February 13, 2012

Why Progressives Need to Go On the Offensive in the Culture Wars

Having been born in the 1970s, raised in the 1980s, and having reached adulthood in the 1990s, the culture wars have been raging across America's political landscape for as long as I can remember. The explanation is two-fold. In the first place, the monumental social changes in the 1960s and 1970s prompted a considerable backlash by reactionaries, and then the Right learned to harness that zeal, getting the masses to vote for their plutocrat-friendly economic policies as long as they occasionally threw out some social issue red meat to feast on. For almost all of this time, conservatives have been the culture war instigators, from rolling back abortion to "intelligent design" in schools to referendums against same-sex marriage.

With Rick Santorum seeping his way into the front-runner position and the support given to the Catholic Church's refusal to cover contraception for its employees, the GOP appears, inexplicably to me, to have gone all in on the culture wars in this election year. This is a turn of events that ought to be welcomed by progressives across the country, mostly because the Right's positions on many culture war issues are very unpopular, and if progressives pin these issues on conservatives, they stand to lose support from moderate voters unhappy with the nation's economic state. By fighting the culture wars on the offensive, progressives can also expose some of the fundamental fissures in the conservative coalition, and thus help divide their enemy.

Case in point is New Jersey governor Chris Christie. The state legislature is about to approve a bill allowing for same-sex marriage, but Christie has pledged to veto it. Of course, he is trying to weasel out of having to veto the bill, preferring to have the issue decided by a voter referendum. Why is he being so cowardly? Essentially, because he is stuck in a tough bind. On the one hand, if he votes in favor of the bill, he might get broad support in New Jersey, but doing so means the end of his national political aspirations, because the social conservatives in the Bible Belt will abandon anyone who supports gay marriage. On the other hand, if he votes against the bill, he retains national support, but stands to lose a lot of support from New Jersey voters, endangering his reelection. American attitudes towards same-sex marriage have changed dramatically in the last decade, and the young upcoming generation is much less hung up on it than their elders. For the GOP to be branded the party of homophobia means lasting damage to their image for years to come.

Much the same could be said when it comes to reproductive rights for women. Instead of just harping on the abortion issue, where some of the candidates for president ascribe to a highly unpopular ban on abortion even in cases of rape or incest, conservatives have upped the ante by going after contraception. Now that they have done so, progressives need to hold conservatives' feet to the fire, and constantly push them on their stance on contraception. As with gay marriage, moving to the right will kill their chances with moderates, moving to the left erodes support among the base. It's really a win-win for progressives: either Republicans placate their base, or they take more progressive stances on the issues.

This post might sound a little crass, but time has taught me that politics is a street fight, and if the other side brings a gun, you best not be fighting with a knife.

With Rick Santorum seeping his way into the front-runner position and the support given to the Catholic Church's refusal to cover contraception for its employees, the GOP appears, inexplicably to me, to have gone all in on the culture wars in this election year. This is a turn of events that ought to be welcomed by progressives across the country, mostly because the Right's positions on many culture war issues are very unpopular, and if progressives pin these issues on conservatives, they stand to lose support from moderate voters unhappy with the nation's economic state. By fighting the culture wars on the offensive, progressives can also expose some of the fundamental fissures in the conservative coalition, and thus help divide their enemy.

Case in point is New Jersey governor Chris Christie. The state legislature is about to approve a bill allowing for same-sex marriage, but Christie has pledged to veto it. Of course, he is trying to weasel out of having to veto the bill, preferring to have the issue decided by a voter referendum. Why is he being so cowardly? Essentially, because he is stuck in a tough bind. On the one hand, if he votes in favor of the bill, he might get broad support in New Jersey, but doing so means the end of his national political aspirations, because the social conservatives in the Bible Belt will abandon anyone who supports gay marriage. On the other hand, if he votes against the bill, he retains national support, but stands to lose a lot of support from New Jersey voters, endangering his reelection. American attitudes towards same-sex marriage have changed dramatically in the last decade, and the young upcoming generation is much less hung up on it than their elders. For the GOP to be branded the party of homophobia means lasting damage to their image for years to come.

Much the same could be said when it comes to reproductive rights for women. Instead of just harping on the abortion issue, where some of the candidates for president ascribe to a highly unpopular ban on abortion even in cases of rape or incest, conservatives have upped the ante by going after contraception. Now that they have done so, progressives need to hold conservatives' feet to the fire, and constantly push them on their stance on contraception. As with gay marriage, moving to the right will kill their chances with moderates, moving to the left erodes support among the base. It's really a win-win for progressives: either Republicans placate their base, or they take more progressive stances on the issues.

This post might sound a little crass, but time has taught me that politics is a street fight, and if the other side brings a gun, you best not be fighting with a knife.

Sunday, February 12, 2012

Thoughts on the Walkman

That sight, of course, is really nothing new. While our new gadgets can hold more and different kinds of entertainment, the ability to exist in public listening to music that no one else can hear dates back to the Sony Walkman's first appearance on the market in 1979. Like Xerox and Kleenex, the brand name quickly became applied to all such similar devices. I still remember when my older cousin Michelle, who had an impressive collection of Top 40 tapes, let me listen to her walkman. I can't recall what song it was, but I was amazed that I could indeed walk around without any cords to hold me back (remember, this is before the popularization of cordless phones, back then everything had to be attached to the wall.)

I received my own first walkman for Christmas in 1986. This being my family, I got a cheap knockoff that burned through batteries with a vengeance and didn't have a rewind button. For that same Christmas I received The Beatles' 20 Greatest Hits on tape, the first cassette I listened to on my prized new device. (There's a picture of me in a photo album at home on Christmas listening to my walkman while looking over the rules for Axis and Allies, which was my other main Christmas gift. Looking back on it, that was one of the best Christmases ever!) I gave that tape quite a workout over the years, mostly since it was almost exactly as long as it took my family to drive from my hometown to my grandparents' farm seventy miles away, a trip we made quite often.

The walkman proved indispensible on family road trips, since I could lose myself in the music and not have to socialize. This was especially important as I got older, when my musical tastes tended towards stuff that was quite a bit weirder and more jarring than the John Denver and Carpenters tapes my parents took on every road trip. The walkman was also a convenient way to pretend that I didn't hear when my mom asked us kids to pray a decade of the rosary. (Yes, I come from a very Catholic family.)

Of course, the walkman giveth and the walkman taketh away. I was pretty anti-social in high school, and on the many debate and band bus trips I took over those four years I tended to retreat into my own private musical world. Looking back on it, I was missing a chance to socialize and even, yes, to talk to young females. One girl on the debate team that I had a crush on my senior year was sweet on me, but it took months to make progress because I was more interested in listening to Jimi Hendrix or Dinosaur Jr (they provided two of my favorite songs to get psyched to before debate rounds my senior year. Yes, I am a nerd.)

So yes, our gadgets can blind us to the wealth of experience and beauty that surrounds us on a daily basis. That being said, I've often used walkmen and iPods to enhance experience. When I travel by train from Newark to New York City by myself, I like to cue up a special New York playlist to get in the mood. (Cat Power's cover of "New York, New York" is one of my favorites in this regard.) When I was a graduate student I liked to go for walks on grim winter days and wallow in the desolateness of a gray sky over the windswept prairie with "World" by the Bee Gees or "She's a Jar" by Wilco cued up on my discman (I was a late adopter of the iPod, as I am with most tech.) Perhaps if we remember that we control our gadgets, and that our gadgets don't control us, we can intensify experience rather than negate it.

Thursday, February 9, 2012

The Revenge of the Birchers: the Republican Party's Current Woes in Historical Context

As Karl Marx once quipped, history repeats itself: first as tragedy, then as farce. Way back in the 1950s, the John Birch Society and other affiliated paranoiacs threatened to gain control of the Republican Party and the conservative movement at large. Prominent conservative leaders like William F. Buckley and Barry Goldwater managed to keep the wolves of conspiracist insanity at bay, forging a powerful new conservative wing of the GOP in the process, culminating in the election of Ronald Reagan. Hard to believe, but the Gipper looks positively moderate compared to the wackos on the hard Right decried by Buckley and company. Represented by Father Coughlin and other anti-Semitic, quasi-fascistic hate mongers in the thirties, and by McCarthyite witch-hunters in the fifties, they saw wicked conspiracy everywhere, to the point of labeling Dwight Eisenhower a Soviet puppet.

Venerable historian Richard Hofstader once famously defined a "paranoid style in American politics," and the Birchers, McCarthyites, and Coughlin devotees certainly fit the bill. They are the political grandchildren of the Anti-Masons and Know Nothings. That paranoid style has never died out in this country, and seems to have stormed its way back into the mainstream with the rise of the Tea Party. Having once swept the tinfoil be-hatted crowd into the closet, the Republicans let loose the dogs of paranoiac politics in order to win the elections in 2010. Like the proverbial sorcerer's apprentice or Victor Frankenstein, however, they have lost control over their creation, which now threatens to destroy them.

This week, amidst the annual barking at the moon at CPAC's conference and Rick Santorum's trifecta of wins in states where he did not have to face tidal waves of corporate advertising against him, it has become totally obvious that lunatics are running the asylum in the Republican party. Confirming this assessment, the New York Times reports this week that many Tea Party groups have been acting locally to derail sustainable energy and public transportation, proclaiming both to be part of a UN plot for world domination. Ron Paul, a candidate who has the biggest grass roots support among the young Republican activists, is a classic paranoiac whose old newsletters preached coming armageddon, and whose devotion to the gold standard reflects the long tradition of anti-bank paranoia in American politics. Steve King, one of the party's more prominent members, today spouted fear and paranoia at CPAC over the eradication of old-fashioned, inefficient lightbulbs, which for some reason has become a cause celebre in certain corners of the Right. His obsession seems wacky to me, but it has taken on the quality of common sense in the conservative media.

The rhetoric of even the mainstream sectors of the party reflects the paranoid style. Like the Know Nothings of yore who depicted Catholics as puppets of a foreign pope, Barack Obama's political opponents consistently portray him as a foreign force out to corrupt and alter America. Newt Gingrich has claimed that the president is a Kenyan socialist hostile to Western (i.e. white) civilization. Mitt Romney, supposedly the moderate option, warns that he needs to be president in order to "keep America American," as if the current president were conspiring to change the nation's very being.

My one hope is that all of this paranoid raving and lunacy will push the GOP so far out of the mainstream that voters will strongly rebuke it at the polls. My fear, however, is that many Americans dissatisfied with the current economic situation will vote for Republicans assuming that they represent a centrist alternative, not a vehicle for extremist ideology.

Tuesday, February 7, 2012

Baseball Card Memories

As usual this time of year, I've got cardboard fetishes on the brain. With the Super Bowl over, my mind is free to dream of baseball season, and pitchers and catchers reporting to camp in only a couple of weeks. With each passing year I cherish more and more the start of baseball season and its promises of hope and renewal, and with it green grass and the warmth of the sun. When I was younger and my baseball enthusiasm had just been sparked, this was the time of year when I eagerly set out to buy wax packs of the new sets of baseball cards at the local Walgreens and Woolworth's.

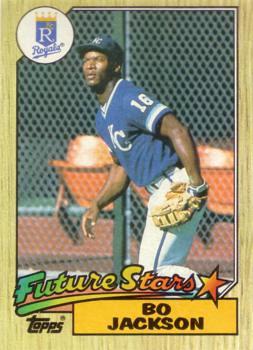

My collecting was most intense in the years 1987-1989. In '89 I entered junior high and switched my collecting habits from baseball cards to comic books, and by 1991 I would be on my way to being the music junky that I still remain today. My collecting years happened to coincide with the Golden Age of baseball cards. Almost all of the other boys at school were into it, and we traded cards in our basements after school and on the playgrounds during recess. Card collecting became a big time hobby; I still remember buying copies of Beckett's Baseball Card Monthly at the local card shop and tracking the prices of my most valuable rookie cards like they were valuable blue chip stocks: Bo Jackson, Will Clark, Greg Maddux, and Mark McGwire. Trading could be ruthless as anything on Wall Street. I still remember the time I made a kid cry because I basically swindled him out of a 1986 Topps Pete Rose card. (They were considered especially valuable in the brief period between his breaking of the career hits record and his public disgrace.)

My main frustration in collecting arose from my biggest frustration in life at that time: I lived in an isolated Nebraska town. This meant that in 1987, my first big summer of collecting, I could never find packs of Fleer or Donruss cards, only Topps or small, cigaratte-pack sized miniserieses from the other brands. For that reason I have more 1987 Topps cards than of any other series; by the end of the summer there was a massive stack of pink planks on my dresser, the unpalatable pieces of gum that came in every pack. The gum's presence, however, meant that I didn't have to pay sales tax on wax packs of Topps, which cost a mere forty cents. Since I got paid the princely sum of two dollars every time I mowed the lawn, I could run out immediately to the local Walgreens and buy five whole packs, eighty five cards in all.

In 1988 I could at least get Donruss cards easily, and one of my proudest moments was when I saved up enough cash to buy an entire box of thirty-six packs. Opening, surveying, and organizing those cards occupied my mind and time for weeks on end. Being a ginger-complected kid averse to the blazing sun of a scorching Nebraska summer, this suited me just fine. At the beginning of the season I was enomored with the series put out by Score, the new kid on the block who put their cards in plastic rather than wax paper, a sign of greater sophistication in my eyes. The card buying highlight of that summer, however, was purchasing some O-pee-chee cards on a family vacation to Manitoba. In the Canadian version of Topps, the information on the back was in both French and English!

During the next year I went back to Topps and flirted a bit with Fleer. That summer I worked my first detasseling job, which meant that I had less time to pore over statistics and search out missing commons. My first big purchase with my first summer job was a Nintendo, and my adolescent mind concentrated on defeating Piston Honda in Mike Tyson's Punch Out, rather than cracking open new packs of cards. In retrospect, it looks like I got out at the right time. Upper Deck put its first series out in 1989, a set of cards geared less towards kids and more towards adult collectors. They charged 99 cents a pack, a high price that negated their obvious high quality in my eyes. Because I was just one of millions of avid collectors, the cards themselves are practically useless from an investment standpoint these days. However, I can't wait for the rush of memories they will bring me when I finally get to look at them again.

*******

Here are some sets I remember, some good some bad.

1987 Topps

This was the set I cut my teeth on, and one that I think still looks great today. It was kinda retro, with the wood background and chunky 1960s font

1987 Fleer

This was the set I wanted really bad, but couldn't get in my hometown. Although I will always have a soft spot in my heart for Topps, the cardboard on Fleer's cards was less flimsy, and the backs were much more interesting and colorful.

1988 Donruss

Nowadays this design looks dated, but at the time I thought it was much superior to what Topps and Fleer were doing. I especially liked that in 1988 Donruss decided to portray pitchers like Fernando Valenzuela batting, rather than on the mound.

1991 Fleer

After my most intense card-buying days were over I'd still pick up a pack or two. Despite the praise I just lavished on Fleer, their all-yellow 1991 set stung the eyes.

After my most intense card-buying days were over I'd still pick up a pack or two. Despite the praise I just lavished on Fleer, their all-yellow 1991 set stung the eyes.

1988 Fleer

Doesn't this design just scream 1988? For some reason the 1988 Fleer cards had all kinds of oddball photos, like this one featuring Tim Flannery.

Doesn't this design just scream 1988? For some reason the 1988 Fleer cards had all kinds of oddball photos, like this one featuring Tim Flannery.

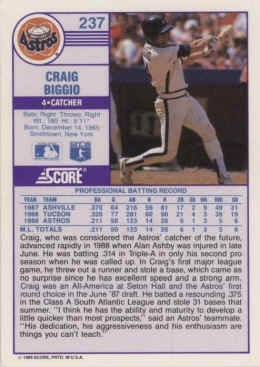

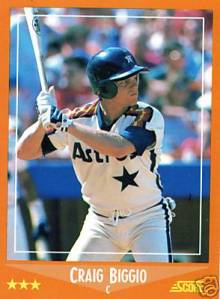

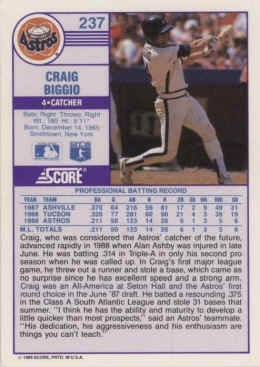

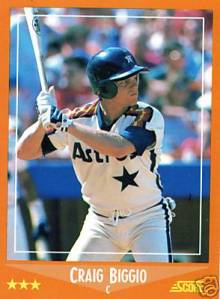

1988 Score

Although the 1987 Topps is my favorite for sentimental reasons, the title of highest quality set belongs to the 1988 Score series. All of the photos were action shots, much more interesting than the endless potrait shots Topps used in '88. The backs were the real revelation: a second color photo and in-depth narratives. Unlike the later Upper Deck, Score managed to walk the fine line between having a beautiful design and remaining a kid's item that could be bought with lawn mowing and paper-delivery money. Once baseball card companies stopped trying to appeal to that demographic, the most essential one for their survival, historically, the downfall really began.

Footnote: Those interested/obsessed with baseball cards must check out Josh Wilker's book and blog Cardboard Gods. My musings on the subject are rather amateur by comparison.

My collecting was most intense in the years 1987-1989. In '89 I entered junior high and switched my collecting habits from baseball cards to comic books, and by 1991 I would be on my way to being the music junky that I still remain today. My collecting years happened to coincide with the Golden Age of baseball cards. Almost all of the other boys at school were into it, and we traded cards in our basements after school and on the playgrounds during recess. Card collecting became a big time hobby; I still remember buying copies of Beckett's Baseball Card Monthly at the local card shop and tracking the prices of my most valuable rookie cards like they were valuable blue chip stocks: Bo Jackson, Will Clark, Greg Maddux, and Mark McGwire. Trading could be ruthless as anything on Wall Street. I still remember the time I made a kid cry because I basically swindled him out of a 1986 Topps Pete Rose card. (They were considered especially valuable in the brief period between his breaking of the career hits record and his public disgrace.)

My main frustration in collecting arose from my biggest frustration in life at that time: I lived in an isolated Nebraska town. This meant that in 1987, my first big summer of collecting, I could never find packs of Fleer or Donruss cards, only Topps or small, cigaratte-pack sized miniserieses from the other brands. For that reason I have more 1987 Topps cards than of any other series; by the end of the summer there was a massive stack of pink planks on my dresser, the unpalatable pieces of gum that came in every pack. The gum's presence, however, meant that I didn't have to pay sales tax on wax packs of Topps, which cost a mere forty cents. Since I got paid the princely sum of two dollars every time I mowed the lawn, I could run out immediately to the local Walgreens and buy five whole packs, eighty five cards in all.

In 1988 I could at least get Donruss cards easily, and one of my proudest moments was when I saved up enough cash to buy an entire box of thirty-six packs. Opening, surveying, and organizing those cards occupied my mind and time for weeks on end. Being a ginger-complected kid averse to the blazing sun of a scorching Nebraska summer, this suited me just fine. At the beginning of the season I was enomored with the series put out by Score, the new kid on the block who put their cards in plastic rather than wax paper, a sign of greater sophistication in my eyes. The card buying highlight of that summer, however, was purchasing some O-pee-chee cards on a family vacation to Manitoba. In the Canadian version of Topps, the information on the back was in both French and English!

During the next year I went back to Topps and flirted a bit with Fleer. That summer I worked my first detasseling job, which meant that I had less time to pore over statistics and search out missing commons. My first big purchase with my first summer job was a Nintendo, and my adolescent mind concentrated on defeating Piston Honda in Mike Tyson's Punch Out, rather than cracking open new packs of cards. In retrospect, it looks like I got out at the right time. Upper Deck put its first series out in 1989, a set of cards geared less towards kids and more towards adult collectors. They charged 99 cents a pack, a high price that negated their obvious high quality in my eyes. Because I was just one of millions of avid collectors, the cards themselves are practically useless from an investment standpoint these days. However, I can't wait for the rush of memories they will bring me when I finally get to look at them again.

*******

Here are some sets I remember, some good some bad.

1987 Topps

This was the set I cut my teeth on, and one that I think still looks great today. It was kinda retro, with the wood background and chunky 1960s font

1987 Fleer

1988 Donruss

Nowadays this design looks dated, but at the time I thought it was much superior to what Topps and Fleer were doing. I especially liked that in 1988 Donruss decided to portray pitchers like Fernando Valenzuela batting, rather than on the mound.

1991 Fleer

After my most intense card-buying days were over I'd still pick up a pack or two. Despite the praise I just lavished on Fleer, their all-yellow 1991 set stung the eyes.

After my most intense card-buying days were over I'd still pick up a pack or two. Despite the praise I just lavished on Fleer, their all-yellow 1991 set stung the eyes.1988 Fleer

Doesn't this design just scream 1988? For some reason the 1988 Fleer cards had all kinds of oddball photos, like this one featuring Tim Flannery.

Doesn't this design just scream 1988? For some reason the 1988 Fleer cards had all kinds of oddball photos, like this one featuring Tim Flannery.1988 Score

Although the 1987 Topps is my favorite for sentimental reasons, the title of highest quality set belongs to the 1988 Score series. All of the photos were action shots, much more interesting than the endless potrait shots Topps used in '88. The backs were the real revelation: a second color photo and in-depth narratives. Unlike the later Upper Deck, Score managed to walk the fine line between having a beautiful design and remaining a kid's item that could be bought with lawn mowing and paper-delivery money. Once baseball card companies stopped trying to appeal to that demographic, the most essential one for their survival, historically, the downfall really began.

Footnote: Those interested/obsessed with baseball cards must check out Josh Wilker's book and blog Cardboard Gods. My musings on the subject are rather amateur by comparison.

Saturday, February 4, 2012

A Good Bar is Hard to Find

Since I have moved out to New Jersey, my life has changed dramatically. I eat healthier, walk more, and spend very little time in bars. The first two developments are welcome, the last, I must admit, makes me a little sad. Some of the best times of my life have been in bars, and I have yet to find an institution better for washing the grime and frustrations of the working week off of my back. Granted, my spending less times in bars is the result of living with my wife, but recently, when I stopped into a corner Irish pub for a pint with a work chum after the school day was done, I forgot how much I loved life behind those swingin' doors, as the song goes. Bars have often been a friendly port of call when traveling in unfamiliar places. Last year, during a trip to New Haven, I had some wonderful conversations with the patrons at a storied dive. When I first moved to Michigan, I quickly established some homes away from home that made my life bearable. On the other hand, the lack of a good bar is a real drag on my quality of life. Back when I lived in Texas, my friends and I went out for drinks with friends quite often, but never enjoyed the establishments where we socialized, which were either over-priced, lame, full of students, or all three. (Of course, a good bar opened there a month after I left.) So what makes a good bar? Here are some criteria that I have come up with after years of experience.

Atmosphere

A good bar is a place where you want to settle in and spend some time. The first bar that I ever truly embraced was the Dubliner, in downtown Omaha. It's a basement Irish pub with an extra whiff of dank that always made me feel like I was spending time in a warm, jovial cave. I could spend hours down there, and never feel that any time had passed. For me, that is the test of a homey bar. Does last call come as a surprise since you haven't been looking at the clock? Is so, you've found your place.

Decor is a crucial element in setting the atmosphere. In my experience, wood-panelled walls are the sign of a quality establishment, since it means it's a joint that still draws in plenty of paying customers without updating the interior since at least the 1970's. Sometimes decor can keep a wretched bar from being unbearable. My local in Texas was usually full of obnoxious students, had nothing better than Rolling Rock on tap, and bartenders who didn't know how to mix Manhattans. However, it had some of the most unintentionally hilarious and endlessly fascinating wall hangings of any bar I've known. Back in the 80s and 90s, it had also been a music venue, and pictures of the bands and artists desperate enough to play in a last-chance shit-hole town stuck in the back woods of East Texas were now immortalized by the framed black and white promotional pictures hanging on the wall. Because of the time and place of these photos, there were more bad mullets and silly mustaches than you'd see at a tractor pull. Another dive I frequented in Chicago left much to be desired, but I was always entranced by the giant clock above the bar, which had the face of former mayor Richard J. Daley painted on it.

Quality Beers on Tap

There are some bars that I love that fail this test, but they must have a musty, homey character of the highest quality, like Jimmy's in Chicago. This place was so dark (before its later remodeling) that I swear I could never see the ceiling. Unless a bar can reach that high standard of atmosphere, it must serve something on tap surpassing the standard Bud, Miller, and Coors. Life is too short to spend it drinking the watered-down swill peddled by the megabrewers. My local in Grand Rapids won my heart from the first, since it had twelve shiny taps dispensing micro-brewed and imported goodness.

A rare bar without good beer can pass this test by having exceedingly shitty beers on tap, if the bar is divey enough. For example, I once spent a few evenings in a place called The Brass Rail (a plus) whose bathrooms smelled so awful that just opening the door to them gave the entire establishment a stench of urinal cakes (another plus), and contained an antiquated jukebox with 45s instead of CDs (huge plus) that allowed me to spin tunes like "Kentucky Rain" and "King of the Road" for a quarter (mega-plus!). This place had Miller High Life and Pabst Blue Ribbon on tap (before it was a hipster beer), and a cooler that dispensed forty-ounce bottles of Mickey's Malt Liquor to the neighborhood ragamuffins. In the context, these deficiencies of beer quality added to The Brass Rail's priceless atmosphere, rather than making it uninhabitable.

Understanding and Competent Staff

Establishing a relationship with bartenders and bar maids is a skill that every seasoned drinker knows well. After I moved to Michigan I spent a lot of time at a bar where I hated the atmosphere but liked to go because the staff were so good to me. Every third drink was free, and there were always interesting conversations to be had. At my local, one of the bartenders became legendary among my friends for his ability to keep all of his orders in his head, and to get us our bubbly pints faster than you could say Jack Robinson, even at the height of happy hour mania. I also tend to like bar staff who take the piss. For instance, at a place that I liked in Chicago, one waitress called me a "nancy boy" for ordering my whiskey on the rocks, rather than straight up. Rather than being offended, I was honored to be served by someone who cared.

On the other hand, shitty service can ruin a night out. Whenever one of my friends gets a pint with half an inch of beer missing off of the top, he calls it a "Hamilton's pour," in (dis)honor of a poorly staffed pub bearing the name. Some bar staff seem to think that their good looks, rather than responsiveness, ought to earn them tips. One such waitress at the otherwise wonderful Dubliner had my friend Dave and I ready to put our table on fire if it meant drawing our waitress from flirting with an admiring table of frat boys. If you belly up to a bar and ask for any kind of cocktail more sophisticated than vodka and cranberry juice and are met with a slack-jawed look of incomprehension, or they put grenadine in your Manhattan, slowly back away and never darken that establishment's door ever again.

Agreeable Clientele

If you're gonna spend a lot of time in a place, it has to be spent with people you actually want to be around. This was always a problem in grad school, because seemingly promising establishments would suddenly get overrun by hordes of ass pants sporting bleached blondes and spiky-haired, thick-necked bully boys wearing white baseball caps from the local undergraduate population. I tend to like bars full of serious drinkers, the type of joints that a friend of mine calls "alkie bars." Their patrons typically go the bar as a place of meditation and contemplation, and since they've got so much swirling around in their heads, make for good company. My favorite bars are the places where I've had interesting conversations with complete strangers.

Food

A bar does not necessarily need food, but it doesn't hurt. After all, you don't want to have to actually leave and go somewhere else to eat, do you? Bars with run of the mill food are a dime a dozen, the sign of a bar with good food is that they have unique items on their menu. For instance, my fave bar in Michigan had an eponymous sandwich, "The Logan" on the menu, which vanquished many a hardy punter. They also served free pizza on Sunday (along with $4.75 pitchers of PBR), a true embarrassment of riches. Failing such unique attributes, quality burgers and free popcorn are always good signs.

Intangibles

Of course, finding the right bar, like finding the right life partner, is not a matter of constructing a checklist. There has to be an extra-special bond that surpasses articulation between you and the bar. I've been in many bars in all kinds of places in my time, but a precious few conform to this standard. In my memory, they are like old friends, and they bring me great joy when I get to visit them after years apart. Hopefully I will find one again before my time is up.

Wednesday, February 1, 2012

Classic Album: Kraftwerk, Man-Machine

There are a small number of artists who can claim to have completely revolutionized popular music. Some of them are obvious: Louis Armstrong, James Brown, Bob Dylan, The Beatles, etc. Some fly under the radar, especially in this country. For a long time, I thought of Kraftwerk as a kind of punchline to a joke, a group that embodied Teutonic rigidity and humorlessness, the musical version of Dieter from the old SNL sketch "Sprockets." I'd always known they'd cast a long shadow over the musical landscape, practically birthing the electronica genre single-handedly and greatly influencing hip-hop, evident in the samples used by Afrika Bambaataa and Jay-Z. In the last few years, though, I've really begun to appreciate their work as great music, rather than the roots of something else.

I have all of their classic albums (Autobahn through Computer World) on vinyl, and recently, and finally, acquired 1978's The Man-Machine. Trans-Europe Express is probably a more monumental album, and Autobahn a bigger breakthrough, but I think of The Man-Machine as the true culmination of Krafwerk's mission. They are all wonderful to listen to on vinyl, because it combines the sleakness of their electronic sound with the warmth of analogue. It makes a lot of sense to combine those elements, since Kraftwerk's songs deal with modern humanity's relationship with technology. We are natural, analog beings increasingly framed and constrained (and enhanced as well) by our digital devices. As the title indicates, Man-Machine explores these themes in great depth. Other Kraftwerk records zero in on specific technologies, such as cars (in Autobahn), radio and atomic energy (Radio-Activity), computers (Computer World), trains (Trans-Europe Express) and bicycles (Tour de France.) The Man-Machine seems to take humanity, transformed by technology into something new and no longer human, as its theme.

The album starts with the percussive pulse of "Robots," which sounds more like modern techno music than anything Kraftwerk had created up to that point. The sounds have gotten more complex, but the beat and the simplicity of the melody remain from Kraftwerk's earlier work. It's easy to lose oneself in the song's seductive repetition, becoming like the robots who sing the song. The next track, "Spacelab," retains the pulsing beat, but is more instrumental, and almost mournful, trying to replicate the loneliness of a almost-deserted space station. It's the kind of thing you could imagine HAL humming to himself. The last song on the first side, "Metropolis," seems to reference the famous 1920s German sci-fi film of the same name, imagining a fast moving train through a futuristic city. The alternating, pulsating base of the song reminds of of Giorgio Moroder-style disco a la Donna Summer's "I Feel Love," except crafted for robots rather than polyester bedecked disco dancers. I love listening to "Metropolis" on my morning commute train ride into the city; it's the perfect soundtrack for passing over the river from mundane, rusty Jersey into the bright lights of the Big Apple.

Flip the record over (again, an interesting thing to do with an artifact that sounds so futuristic) and Kraftwerk begins with the most song-like song on the album: "The Model." There might be more words in this one track than on all the others on the album put together. The icy chords replicate the glittering glamor of the model's world, as well as her personality. Ironically, this song is the only one on the record about a person, but she sounds just as robotic as the machines featured elsewhere. "The Model" flows into the more impressionistic "Neon Lights," a kind of wistful homage to the beauty of the city at night. It's probably the most beautiful song on the record, containing real human warmth beneath its metronomic sheen.

That feeling leaves on the last track, "The Man-Machine," an almost brutally repetitive song that might very well be an apt prophecy of where the human race is headed in the digital age. I suspect it is an homage to the robot from the film Metropolis, dubbed the "man-machine" by its mad scientist creator. Kraftwerk subtly show us our modern, machine-age condition, but do it through works of great, and simple-seeming beauty, rather than philosophical treatises. Twenty years from now, I am sure The Man-Machine will sound just as relevant.